Jane Campion, one of the world’s great film directors, has had it with the movies. It is eight years since she last made a full-length feature (the Keats biopic Bright Star), and 14 years since her sexually explicit thriller In The Cut almost did for her career. Now she is having a Gloria Swanson moment: she’s still big, it’s just the pictures that got small. Movies, she says, have become conservative cash cows. “The really clever people used to do film. Now, the really clever people do television. I’d been feeling, in the film world, that if you come up with ideas, and you share them, the first concern is: how is the audience going to react?” Television has reinvigorated her.

“Cinema in Australia and New Zealand has become much more mainstream. It’s broad entertainment, broad sympathy. It’s just not my kind of thing. As a goal, to make money out of entertaining doesn’t inspire me. But in television, there is no concern about politeness or pleasing the audience. It feels like creative freedom.”

The first series of Top Of The Lake, co-written and directed by Campion for television, was visually stunning (set on New Zealand’s breathtaking South Island), thrilling (you never knew where you were going in this police procedural about a missing girl), superbly acted (Elisabeth Moss as the troubled detective Robin Griffin is terrific) and brilliantly bonkers (the commune of separatist-feminist-utopian women led by Holly Hunter‘s guru takes some beating on the fruit-loop front). Take Twin Peaks, transplant it to the New Zealand wilderness, chuck in an extra smattering of crazy, and you’ve got Top Of The Lake.

Four years later, the New Zealand director has completed a second series, and it is every bit as compelling. The location has now switched to Sydney, and Hunter’s commune has been replaced by a group of dysfunctional young men addicted to pornography. Hunter is gone and Nicole Kidman has arrived, playing the adoptive mother of the daughter Griffin had to give up (played by Campion’s own daughter, Alice Englert ). And, of course, there is another horrible crime at the heart of it - this time, trafficking. We meet at a hotel in Soho, central London.

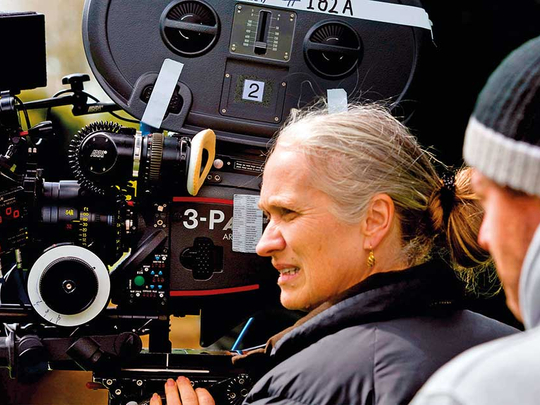

Before the interview, Campion’s publicist tells me that the film-maker is worried - she just wants to talk about her work, no personal stuff - but it soon emerges that the two are indistinguishable. Within six minutes, Campion has taken me through her menopause, explaining why it was a positive experience, even if women her age are regarded as invisible. Campion, aged 63, is every bit as unusual as her work: tall, tactile, slightly awkward, with long, white hair and a striking face. She is warm and open, with an easy manner that makes you feel you have known her for decades - though that may be because I have, through her films.

I saw her first movie, Sweetie, nearly 30 years ago, a tragicomedy about a love-hate relationship between two sisters. It was as funny as it was upsetting, and full of what became the director’s signature touches: naturalistic (no background sound track), dreamily surrealistic (everybody reacts a beat slower than they should), scatological (one of the girls takes a pee in the driveway), non-judgmental. Which is the stranger - or the more normal - of the two sisters? Who knows?

Despite a privileged upbringing, Campion has always sided with outsiders. Her maternal great-grandfather was a successful shoe manufacturer and her mother, Edith, inherited money with which she and Campion’s father, Richard, set up New Zealand’s first national theatre, with Edith acting and Richard directing. Campion says it sounds much grander than it was. Her parents struggled to make ends meet and the theatre was downsized to a company that toured schools. Edith (a fine actress who makes a memorable appearance as an English teacher in her daughter’s adaptation of An Angel At My Table, the autobiography of the New Zealand writer Janet Frame) suffered debilitating mental illness. “She was a beautiful woman, but seriously depressed. She tried to kill herself five times. Her parents died of alcoholism. They were both dead by the time she was nine, so she really didn’t know how to be a mother.”

Like Frame, Edith underwent extensive electroconvulsive therapy. Her father, Campion says, was relentlessly cheerful. “He was a bit of a dolphin. He had a good time no matter what, jumping about in the waves.” She grew up with her sister Anna, who is 18 months older and also a writer and film-maker. For many years, the two were ferociously competitive, but are now close. Their brother Michael, born when Jane was seven, went on to be a successful businessman, who works in recruitment.

When she was a teenager, Campion says, she found solace in movies. “Film-makers were my companions and they helped me grow up. I was so inspired. Buuel, Wenders, Cassavetes: they made me feel connected to the world.”

Why did she feel disconnected? “I had no energy or direction.” She was paralysingly inhibited. She studied anthropology at university in Wellington, but had no sense of what she wanted to do with her life. All she hoped was that she would meet a man who would whisk her away and marry her. “I remember thinking that women didn’t really have jobs, they were mothers or supported their husbands.” She says she spent so much time trying to please men, and laughs at her patheticness. Then she discovered art and found a sense of purpose, attending Chelsea School of Art in London and the Sydney College of the Arts. She realised that all the energy she had bottled up or wasted on men could be put to good use. “The best thing that happened to me is, I ended up with no boyfriends. It was absolutely the best thing. At 25, I started to realise that the energy that was tormenting me was going to become my friend. I worked 18 hours a day. I think I’d been quite hidden until that point. I was prepared to do things that wouldn’t work, but at least I would try.”

Campion, who was made a dame last year, soon felt stymied by art and turned to film. In 1980, she made her first short, Tissues - about a father arrested for child molestation - which had a tissue in every scene. She went to the Australian Film, Television and Radio School in Sydney, where she made more short films. There were so many stories she wanted to tell, about her kind of people, “people who fall off the frontier of our society” - the weird, the uncomfortable, the irrational.

When she started out, Campion considered herself primarily a writer. “I had these stories and there was no chance of getting anybody else to do them, so I had to become a director of my own work. I never thought I wanted to be a film director. I’m not actually ambitious per se in terms of a career; I’m just ambitious to achieve the stories and dramas that I’ve come up with.”

Mental illness is a recurrent theme in her work, with the line between sanity and insanity often blurred. In the wonderful An Angel At My Table, Campion tells the story of how Frame came to be sectioned and subjected to repeated electroconvulsive therapy; she only narrowly avoids being lobotomised. Frame, misdiagnosed as schizophrenic, is insecure, neurotic, ill, but she is never portrayed as simply mad. Campion’s work is also profoundly female: I have never seen films so immersed in the everyday experience of women. “I wanted to bring my interests and concerns into the cinema,” she explains. “Psychologically, women are forced to look at the world through men’s eyes. I wanted to put the other point of view: what it felt like to be a woman expressing yourself, being free, doing your human stuff in what is a pretty patriarchal society.”

To start with, she claims she was a useless director. “I was always trying to please everybody.” That’s funny, I say, because I read that you always tell actors to stop trying to please the audience. “That’s right. And that’s what I had to learn to do. I’m just going to do my job really well, ask people what they need and be polite. I was exhausted by trying to please everybody.”

What made her realise it didn’t work? “They didn’t have any respect for me. People respect what works. When they see you’ve done your homework, you’re capable of making a great set and organising everything to make this thing good, they appreciate it. They must know you’re the boss - they need you to tell them what’s going to happen next. And you don’t need to excuse yourself for that.”

Has she had to be competitive to be a director? Well, she says, slightly embarrassed, in many ways she is a gentle, sharing, caring, yoga-loving new-age hippy, but, yes, in others she is extremely competitive. I tell her I play tennis with a couple of directors and they always think they are right on the line calls. Would she challenge every call, too? “Erm... yes? With my co-director on Top Of The Lake, Ariel Kleiman , we are really competitive as well. We can’t help that. It’s part of our nature, but we know it and laugh about it.” How does it express itself? “I want to be better than him. I don’t actually think I am. We both want to be better than the other.”

She adores Kleiman, an Australian writer-director who is only 32. “I see Ariel’s gifts - his elegance, his shots and structure. He’s got this mathematical brain.” She pauses. “He’s better at shots than me,” she says through gritted teeth. “He is a real samurai, a genius. We might be competitive, but we love and support each other.”

Campion’s first two films, Sweetie and An Angel At My Table, were lauded by the critics. Sweetie was entered into a competition at the Cannes film festival in 1989; a year later, An Angel At My Table won the Silver Lion (runner-up prize) at the Venice film festival. But it was The Piano, released in 1993, that made her famous. A baroque romance about a piano-playing mute (Hunter) who falls in love with a retired sailor (Harvey Keitel), the film should have been a small indie gem, but turned into a huge mainstream hit. In 1994, Campion won an Oscar for best original screenplay and was nominated for best director; Hunter won best actress, while Anna Paquin, who played Hunter’s daughter, won best supporting actress at the age of 11.

In 1993, Campion also jointly won the prestigious Palme d’Or at Cannes; 24 years on, much to her disgust, she remains the only female winner.

Campion had married Colin Englert, second unit director on The Piano, a year earlier, in 1992. A few weeks after her triumph at Cannes, their son Jasper was born, with life-threatening complications; he died 12 days later, a trauma that Campion has carried with her for many years. I ask if she is depressive, like her mother. “No. I have been sad when bad things have happened. One would expect to be unhappy when a baby dies, and I certainly was. But I just don’t have that mental makeup where you would get long-term depression. I’m lucky.”

She admits that she has struggled with anxieties and compulsions over the years. “I have been addressing my own madness for some time with yoga and meditation - just becoming aware of it is a big job.” What kind of madness? “Everyday madness. The things you get into your head, going round and round. And believing your thoughts.” Are those thoughts rooted in reality? “They are often just descriptions of anxiety. I’ve actually got a very level system. You probably feel that just sitting near me.” I do: at times, she looks and sounds just like Hunter’s commune leader GJ in Top Of The Lake (GJ’s hair is long and white like hers, though Campion says the character is based on her late friend, the Indian philosopher UG Krishnamurti).

Does her anxiety worry her? “It worried me when I became compulsive, yes. I couldn’t stop thinking about things - feeling hurt or worried. I have been romantically compulsive in my life. I don’t think I’m like that any more. I ended up going to see a therapist for a long time, and that was fantastically helpful.”

Extreme love is a leitmotif in her work, I say; that scene in The Piano when Keitel spots a hole in Hunter’s stocking and runs a finger over it is one of the sexiest in the movies. “Well, certainly, The Piano is in the romantic genre. They say that being a romantic is like a disease in its most extreme form.” A year after Jasper died, Campion’s daughter Alice was born. She continued to work - Holy Smoke, co-written with her sister Anna, starring Kate Winslet and Keitel; and an adaptation of Henry James’s The Portrait Of A Lady with Kidman. In 2003, she made her most controversial film, an adaptation of the Susanna Moore thriller In The Cut, about a teacher who embarks on a dangerous affair. Like The Piano, it was erotic, but this was more explicit - and from a female perspective, of course. In the Observer, Philip French wrote that this was a “feminist director engaging with once taboo subjects”, and that “for all its air of breaking new ground, it was ploughing some familiar furrows”.

“That was a pretty big disaster in terms of the way it was reviewed,” Campion says. Did she think the critics were wrong? “Yes, I did. What was really hard about that was that it was mostly reviewed by males, and they hated the female point of view and the way the women were talking about them as objects. Actually, I do think it is a good movie. There are certain women who tell me it’s one of their favourite films.”

After In The Cut, she took an enforced break from film-making. “I was going to take a break anyway,” she says, “but I found it really easy, because when you have a failure, nobody rings you up or wants you to do anything. I just wanted to be with my kid a bit more and spent four years being more of a mother. I actually had to convince her that, ‘I am your mother.’ “Really? She smiles. “A little bit. She did come with me often when I was working, but she also grew up with another mother, who is her nanny.” By then, Campion and Englert had divorced, and Alice developed an aversion to school. “She’s a very gentle girl. I said to her one day, ‘Come on, get up, let’s go, I’m going to drop you off at school.’ She said, ‘I’m not going and you’d better get used to it. I’m not going to school ever again.’” And she was as good as her word. So for four years Campion home-schooled Alice, devising a curriculum that matched her daughter’s interests, hiring tutors for Shakespeare and poetry.

Campion says she loved that time.

At the age of 13, Alice told her mother that she wanted to be an actor. By the time she had completed her home schooling, she had not changed her mind. “I thought, ‘Oh no!’” Why? “I think it’s just that world of always having to live in public a little bit, and having to get the roles. That relationship with power, having to audition. And so many people want to do it. Why do they want to be an actor? I find that bizarre. Why don’t they want the power?”

Campion suggested she consider university. “Alice said, ‘Mum, I’ve been to the cafeteria at Sydney University and I don’t like it.’” She gets the giggles. “I was like, how can you know from the cafe? But she was just really sure she didn’t like that kind of learning.”

Alice’s character in Top Of The Lake is very troubled, and I ask Campion if working with her made her rethink their relationship. Not really, she says - there is nothing conflicted about their relationship. “I think having a daughter is the best thing that has ever happened to me. Loving someone that much...” She trails off. Later, Alice walks into the room and their closeness is immediately apparent. Like her mother, she seems kind and relaxed in her skin - very different from the brittle, damaged woman she plays on screen.

I ask when she has been her happiest. “When I was really young, pre-10, I was so happy - a kid, just doing stuff. Then you realise there’s something going on that you should be part of, or you should try to be part of. Then you work out that you don’t actually have to be part of that. Loads of people aren’t.” She pauses. “I actually feel happier than ever. I still feel like a child in my heart. But I’ve had to work for that.”

Guardian News & Media Ltd, 2017