London: And so the credits finally roll. Like reaching the end of some heaving biopic, it may take a while for Arsene Wenger to feel able to shake himself back into the real world, to emerge blinking from that life intensely lived as manager at Arsenal, to take off the red and white spectacles and not assess everything through that prism.

Finally, now, he has reached that point that for so long seemed impossible, the trigger which has pushed the endgame button. The mantra that he would always respect his contract, the stubbornness that made it so implausible that he one day would do that, has been blown. The debate bubbled and frothed around him for years, for quite a lot of that turbulent second half of his tenure, but the truth is it was something that Wenger could not easily judge for himself because he was always so immersed.

Wenger’s collaboration with Arsenal sucked them in deep, which is why, for club and man, this break will shudder through the both of them. Moving on, after such a long spell entwined, will be strange.

Maybe it seems like yesterday that he had his first visit to Arsenal. When a 40-year-old manager of Monaco passing through London and he could not quite believe a famous old stadium could exist among what appeared to be ordinary streets full of ordinary houses. He was charmed. Something of the romance of that first meeting never left him as he would in his later years occasionally drive by the facade of the old place, park up and indulge in some nostalgia.

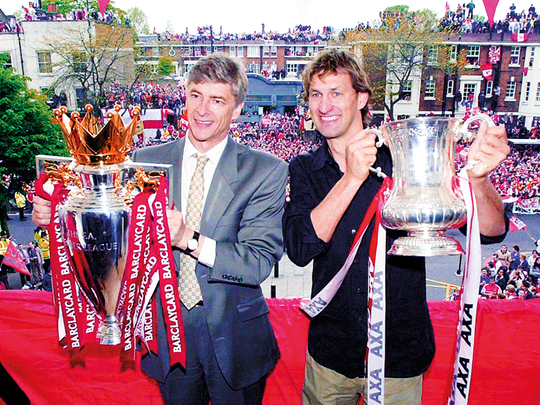

Maybe it seems like yesterday that he walked into a dressing room in the autumn of 1996 to find a squad coming to terms with the fact its inspirational captain, Tony Adams, had only days before announced his struggle with alcoholism. A predominantly British group, with stereotypically British qualities, would soon be open to progressive ideas even if a foreign manager was not initially everybody’s cup of tea. Adams described his own scepticism as “contempt before investigation” but would soon see how much there was to learn from a manager so different to those he came across before. Dennis Bergkamp was already in situ, a fresh-faced arrival with telescopic legs called Patrick Vieira had been ushered in on the incoming manager’s recommendation even before he arrived. Before long Wenger blended old and new perfectly to win the Premier League and FA Cup double.

Arsenal were wowed by him in those early years. The “Arsene Knows” banner that aired frequently epitomised that. Back then dissenting voices were simply nonexistent.

Maybe it seems like yesterday that the team were dubbed Invincibles for turning Wenger’s dream to complete a league campaign without defeat into glorious reality. Those peak years included a Champions League final, and a style of football that was widely admired. Some fans took to using the nickname “Wengerball” to explain the high-speed passing, injected with ingenuity and aesthetic combinations, which were a hallmark of the way they played at their very best.

Maybe it seems like yesterday that the tide began to turn and title bids collapsed amid jokes about the top-four trophy. Years without silverware were clocked up and fingers began to point at Wenger as his new project, to attempt to build a successful team out of youth products educated to believe in the club and its ideals, was picked apart by richer, more ruthless, competitors.

The more recent yesterdays have been brutal at times. There have been humiliations on the pitch, protests off it, and the atmosphere around the club deteriorated to the point where more seats lay empty on a match day as apathy set in, more of the disaffected sought to demonstrate against their manager and the way the club was run.

A glorious history versus an underwhelming present was the nub of the argument that provoked so much friction. In one of his great quotes, Wenger predicted the problems that would ultimately fracture this great footballing relationship. “If you eat caviar every day it is difficult to return to sausages,” he said. It is hard to believe that quote stretches back to 1998, and the weeks after Wenger blazed a trail by becoming the first foreign manager to win the Premier League.

He could have left Arsenal at several points along the way, not least when he knew he was in for a few challenging seasons in the immediate aftermath of the move from Highbury to the Emirates. Finances were restricted, the football landscape was changing rapidly with the arrival of oligarchs and investors from far and wide. He chose not to be tempted by offers from some of Europe’s giants, clubs with more financial muscle and stability, to oversee a huge redevelopment. There was no trophy for that even if Wenger regards that period — keeping the club near the top — as one of his successes.

It is interesting to remember there was no serious fan unrest in those first few seasons post-move. The mood has hardened in the subsequent phase, the years that Arsenal were supposed to be on an even keel and able to compete with anyone. The record signing of Mesut Ozil in 2013 was symbolic of that shift. But, barring the not-to-be-sniffed-at phase of three FA Cups in four recent seasons, Arsenal’s same old problems of falling out of contention for the most eye-catching honours, the Premier League and Champions League, have loaded critiques at the manager’s door.

Wenger became part of the furniture. By the end we all felt we knew him so well, foibles and all. He was a manager who always — always — stood by his values. For better or for worse he did his job with unstinting conviction.

He thinks a lot about the human side of management. He prefers to regard his players as people first and athletes second. He has a keen interest in finances and social policies and a view of the world outside the football pitch. As a man, he has many characteristics that seem contradictory but all go to make up this unique manager. He has a razor-sharp wit but can be absent-minded and clumsy. He is kind and generous but a terribly sore loser. He speaks with confidence in public yet remains very private away from the game. He is addicted to the intensity of the best sporting challenges but loathes personal conflict. He is somehow one of the most liberal-minded of managers and also the most stubborn. As a man, his kindness and generosity are held in the highest esteem by those who know him.

Whatever lies ahead — and there is as much chance of it getting better as getting worse — one man cannot easily fill the void he leaves. He is the last of the managerial overlords, the long-term managers who dedicate decades to one club. After all Wenger’s yesterdays, Arsenal without Arsene will take some getting used to.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd