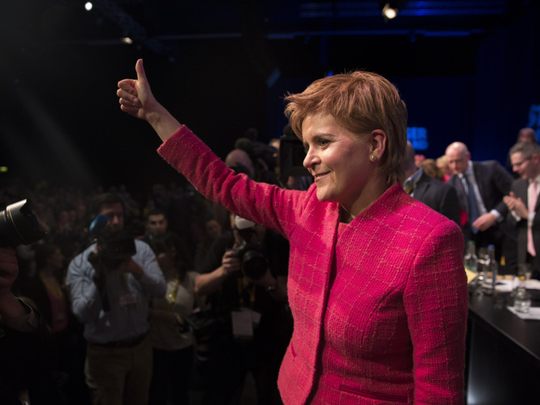

If Nicola Sturgeon thinks she can ride a wave of anti-Brexit sentiment that will carry Scotland all the way to independence as a brand new EU state, she must think again. The dream of seamlessly swapping the chilly isolation of the United Kingdom for the warm embrace of the European Union has already been dashed by an unexpected opponent — Spain.

Foreign minister Alfonso Dastis has been crystal clear about what would happen if Scotland left the UK before Brexit. “If by mutual agreement and by virtue of constitutional change Scotland ended up being independent, our thesis is that it could not stay inside the European Union,” he said this week. “It would have to join the queue, meet the requirements, go through the recognised negotiating system and the end result will be whatever those negotiations produce.”

At the very least that means an independent Scotland would spend a period outside the EU while it waited to rejoin. In the worst-case scenario, it would find its path back to the EU blocked for a very long time. Scots should remember that there is, in fact, no automatic right to membership.

The EU warns that joining as a full member “is a complex procedure which does not happen overnight”. That currently includes having to join the euro — meaning that, should Scotland get that far, it must wave goodbye to the pound. Control of interest rates and other monetary policy will be handled by the European Central Bank (ECB) in Frankfurt. That is a lot farther away than London. It will also have to negotiate the size of its contribution to EU funds. And accession can be blocked by a single member state — like Spain, for example.

Separatist Scots can be forgiven for asking what they have done to annoy the government of Mariano Rajoy — Spain’s conservative prime minister — and his People’s party (PP). The answer is nothing. But at the last referendum the streets of Edinburgh and Glasgow were filled not just with flags bearing the cross of St Andrew. The separatist flag of Catalonia — red and gold, with a white star on a blue triangle — was also being waved, as campaigners pursuing independence for their wealthy north-eastern corner of Spain marvelled at the way their Scottish friends were being allowed to vote.

A warning

Rajoy’s real aim is to stop Catalan independence. If that means blocking Scotland from rejoining the EU for a time, then so be it. Just as Brussels wants the UK to be worse off after leaving the EU, as a warning to others tempted to follow the Brexit path, so Madrid would want Scotland to be worse off if it set the precedent of EU members states (which the UK still is) breaking up internally. That might help dissuade Catalans, Basques and others from trying to follow the same path.

For Scots, then, the current choice is between the Spanish devil and the Brexit deep blue sea. They can belong to a depressed post-Brexit UK, or a marginalised but independent Scotland.

For Catalans the choice is both starker and simpler. With Madrid refusing to contemplate a referendum, independence is simply not on the cards. A mock referendum, or “consultation”, held by the regional government in 2014 has seen the then president of Catalonia, Artur Mas, banned from holding office for two years. A second referendum pledged for later this year could end up with even more dramatic punishments for those who organise it. And a threatened unilateral declaration of independence looks very much like a bluff — which, were it to happen, could see Madrid suspend Catalonia’s current self-government. The EU will not intervene.

Rajoy would welcome a chance to demonstrate to Catalans that, were independence to happen, they would end up outside the EU and be sent to the back of the queue of countries applying for entry. That is his strongest card in trying to dampen separatist sentiment which has grown hugely since the country’s constitutional court reversed parts of a self-government statute that had already been approved at referendum.

British remainers who cling to the hope of somehow stopping Brexit from happening might want to study the Catalan case — and the groundswell of fury that overturning a referendum can provoke.

But Scottish nationalists should not lose hope. If they are patient, and wait for Brexit before leaving the UK, they will have a far better chance of a quick return to the EU. Unlike other applicants, Scotland’s laws already meet all the necessary requirements. And Spain would gain very little from making life difficult for a country that became legally independent outside the EU.

Scotland should wait for Brexit and then rebel. That would provoke glee on the other side of the Channel, with the break-up of the UK serving as a dramatic warning to other EU member states about the dangers of leaving. Indeed, if it waits, Scotland should expect to be cheered back into Europe.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Giles Tremlett is a regular contributor to the Long Read. He is the author of Ghosts of Spain and Catherine of Aragon