At the weekend, I sat in a Parisian cafe, sipping a coffee and reading the reminiscences in Liberation about the events of May 1968. Fifty years ago to the day, more than 300,000 people had marched through those streets demanding the resignation of president Charles de Gaulle, one of the high points of the rebellion. One of the banners held high in the crowd announced: “Those in power are in retreat! Now they must fall!”

Today, the thing that needs saying about 1968 is that it was indeed a liberation, but that it was also a failure. In 1968 it felt as if the European world had come alive again after a long hibernation. Society, ideas and culture changed for the liberal better afterwards. Above all, women’s equality flourished. But political and economic power did not change. Those in power may have been in retreat in 1968, certainly so in De Gaulle’s case. But they did not fall. Mostly they were soon re-elected.

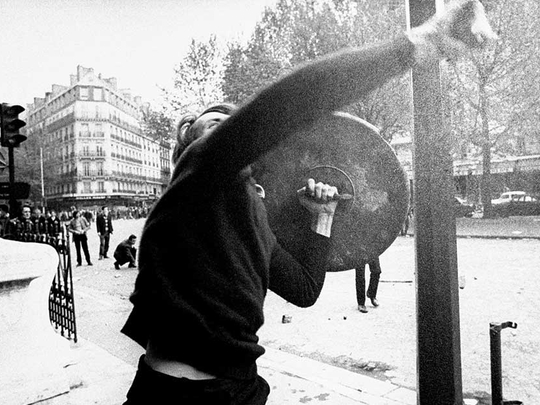

The political failure of 1968 was not just reflected in subsequent elections. The failure was also historic on a larger scale. Half a century on, it is perhaps hard to understand how intensely 1968 felt at the time like a political rebirth — and how intensely that rebirth was sought on the post-war Left. Across Europe, but particularly in France, the events were an often conscious reaffirmation of a form of revolutionary Left politics with deep 19th and early 20th-century roots and echoes. This politics aspired to spark the frustratingly contented working class into a new era of militancy. It took place in the streets and in the factories. It attacked the police and other institutions of power. It sometimes used and consistently romanticised violence. It drew directly on the legacies of 1789 and 1917.

Part of this was further energised by what were then called Third World movements, especially in Cuba and Vietnam. In the end, though, this revolutionism overthrew almost nothing. The Paris events were not the French or the Russian Revolution reborn. May 1968 was less the beginning of a new form of politics, and more the end of an old form. It had more in common with the defeated Springtime of the Peoples in 1848 than with the dubious achievements of the Jacobins or the Bolsheviks.

We all live with that legacy still. After 1968, the revolutionary tradition in Europe was largely spent. No democracy, then or subsequently, was overthrown. Clandestine groups, principally in Germany, Italy and the Basque country, turned to more extreme violence. The Irish Republican Army revived in Northern Ireland. Yet, even this did not last. The guns eventually fell silent. Instead, the nations that changed most radically in Europe were the authoritarian states — not the supposedly repressively tolerant democratic ones.

In 1968, many of us young people on the streets of western Europe called ourselves revolutionaries. No one serious says this any longer. Yet, as the era of British Labour party leader Jeremy Corbyn shows, a romantic attachment to aspects of that old revolutionism still has an allure to some. What I still retain from Britain’s minor 1968 experience is the era’s Europeanism. The films we watched were European. So were the political authors who excited us. Paris was still the greatest city in Europe. In 1968, we bounced down Whitehall doing the Ho Chi Minh hop to the chant of “Paris, London, Rome, Berlin / We shall fight and we shall win.” Four European reference points, please note.

In fact we fought a little but we didn’t win.

Arguably, it is not just the romance of the barricades that has gone now. Even the idea of the popular movement itself is questionable. Extra-parliamentary politics means little, and even peaceful demonstrations do not shift governments.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Martin Kettle is a Guardian columnist.