Over the past seven years, many pointed to the Syrian Constitution of 1950, saying that it ought to be revisited or re-adopted, given that it safeguards a parliamentary democracy and increases powers of the premiership at the expense of the presidency. That charter was penned by an elected assembly of front-line politicians and A-class nationalists, in the immediate aftermath of a turbulent period resulting from two coups that rocked Syria in less than six months. Once finishing its constitutional tasks, it was automatically transformed into a full-fledge parliament.

At the Sochi talks, government negotiators insisted on building upon the present constitution, penned by 29 lawmakers less than one year after outbreak of the current crisis, back in 2012. That charter famously did away with Article 8, which constitutionally designated the Baath Party as “ruler of state and society”. It also scrapped a presidential oath, upholding the Baath Party trinity of “unity, freedom, and socialism”. Articles that mention a socialist economy, education, army and society, were also removed. Sochi delegates agreed to “review” that charter while in early 2017, Russian lawmakers had put forth another draft constitution as well, which will also be debated in the upcoming process. The main sticking points in the Russian draft were the following issues:

n 1) Country’s Name: The Russian draft changes it from “Syrian Arab Republic” to “Syrian Republic”, in order to please non-Arab components of society, like the Kurds, Circassians, Turkmen and Armenians. Arab nationalists from both camps are furious with the suggestion, demanding its annulment.

n 2) Article 3: Included in every Syrian Constitution since 1920, it specifically says that the religion of the president of the republic is Islam. The 1973 draft tried deleting the article, but widespread objection led to its restoration. It means that a Kurdish Muslim from Al Qamishly can become president, but a Damascus or Aleppo Christian cannot. Islamists are fuming with the suggested change, but seculars are seemingly happy with it.

n 3) Presidential Powers: The Russian draft cancelled 23 presidential powers, including the right to name or dismiss a prime minister, the right to chair government meetings, to appoint judges and/or the governor of the Central Bank. It kept the armed forces and security apparatus firmly in the hands of the presidency, however, which prompted the opposition to object, whereas Damascus said no to the reduction of presidential powers.

n 4) Article 111: Found in the 2012 Constitution, says that the president assumes legislative authority when parliament is not in session. Five years ago, many objected to this cause and are likely to make a fuss about it today. n 5) Presidential Term: Despite calls to reduce it to five years, the presidential term was fixed at seven, being one of the longest in the world. In the 1950 constitution, it was renewable only once but many years later, becoming open-ended. It was restored to two-terms only five years ago, but there was plenty of debate on whether this had a reverse effect or not.

n 6) Kurdish language: The Russian draft recognises Kurdish as second-to-Arab in the country’s list of official languages, a suggestion to get drowned by Arab Nationalists, Baathists, and Turkish-backed opposition figures.

n 7) De-centralisation: The draft constitution says that entire territories within Syria will get to elect their own governors and receive a share of their natural resources, without having to share the wealth with Damascus or seek the central government’s stamp of approval for any local issue. It also calls for “local parliaments” that don’t report to Damascus, who elect a new house to represent them in the capital, which rules, side-by-side, with the present parliament. They take the same oath and share power with the premiership and presidency. A majority vote in the joint session of both chambers can bring down a government — something that according to the 2012 Constitution is a right vested only in the hands of the president. A joint vote can also impeach a head of state, which previously and until now, was reserved exclusively for the judiciary, only if he commits an act of treason.

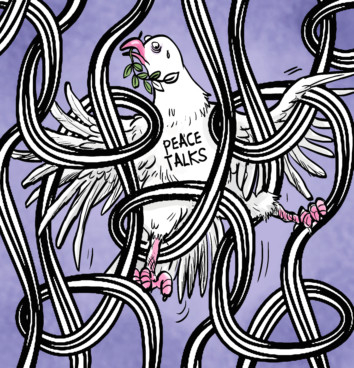

These are no small issues. Apart from agreeing to sit down and talk, the two warring Syrian factions agree on none of the above — meaning that the assembly review, even if carried out with good intentions — might take a very long time. Once through with debating the charter, delegates would have to insert them into a legal document, which is also a lengthy process that might take longer than what many people expected.

Sami Moubayed is a Syrian historian and former Carnegie scholar. He is also the author of Under the Black Flag: At the frontier of the New Jihad.