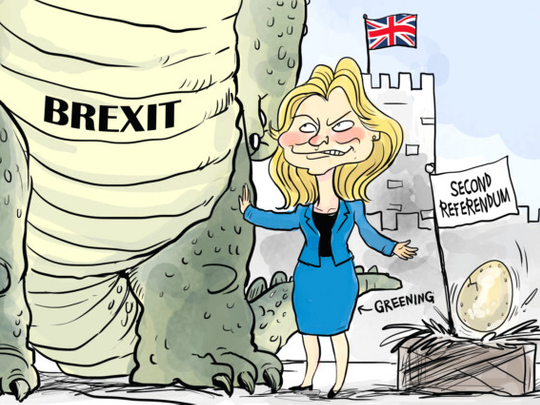

It has not taken long, since the drama of last week’s Cabinet resignations, for the idea of a second EU referendum to gain airtime and significant new adherents. For many months, such an opportunity to reverse or modify the decision of the electorate has been the goal of many: now Justine Greening, a sensible and likeable Conservative, has joined in. Facing the prospect of a deadlocked Parliament that cannot agree on any specific form of Brexit, she argues, only the people can break the stalemate and decide what happens. The voters would be given a new choice between three options of accepting whatever deal is negotiated by Theresa May, leaving with no deal, or staying in the EU after all.

It is a beguiling argument, and it should concentrate the minds of all Tory MPs — partly because it can easily win more supporters and particularly because a second referendum is a completely disastrous scenario. Since the campaign for it will gain further ground if current Conservative divisions continue, it is worth thinking through what exactly it would involve.

The first problem is the obvious one of timescale. Referendums in this country are not held overnight, and would not be remotely fair if they were. Each one requires a special Act of Parliament, which itself takes months to pass. A campaign requires further months for each side to prepare, raise funds, state its case and mobilise supporters.

A referendum held by next June on a deal reached towards the end of this year would still be the fastest such process of legislating for it and holding it that we have ever known. Since time would have to be allowed afterwards to implement whichever outcome, the UK would have to ask for a six or nine-month extension to the March 29 date for leaving the EU. That would be a momentous and hugely controversial decision in itself, and require unanimous agreement among the other 27 members — no doubt at a considerable price. While all that was going on, the uncertainty for businesses, which is for many a bigger problem than any specific outcome, would be at a maximum, with damaging consequences for jobs and investment.

Then there is the immense problem of what the result would really mean. If people voted to leave with no deal, does that mean truly no deal at all? No arrangement for airlines to land, or lorries to cross the Channel, or passport control to work or nuclear material to move? The idea of “no deal” itself covers many possible choices.

Even less clear is the meaning of a vote to stay, three years after we decided to leave. In the meantime the EU has been changing. It has withdrawn the concessions offered to former prime minister David Cameron. It is moving to more integrated military structures. It is trying to agree a common immigration policy, although not currently succeeding. Just as you can’t step into the same river twice, you cannot remain in the same organisation you are leaving without some renegotiation of the terms. Staying would be very complicated — for what form of it would people have voted?

So if we held a second referendum we would have indecision for another year at least, with the prospect of a mass of new and difficult options at the end of it.

That, however, isn’t the worst of it. More worrying still is the damage it could inflict on democracy in the United Kingdom. This would be Parliament saying that even though the country reached a verdict after a long campaign, with a record turnout and a decisive margin, it is not capable of delivering it; that the state cannot honour the wishes of its citizens. Faith in our democratic processes would be correspondingly and severely affected.

Added to this disillusionment would be the effects of a bitterly divisive and vituperative campaign, likely to exceed in its all-round animosity anything we have witnessed in recent decades. Being asked to vote again would to millions of people be a betrayal, the result of establishment resistance to the popular will. On the other side, snatching victory from the earlier defeat would require a full assault on the reputations of those who advocated leaving without a clear plan of how to accomplish it.

Families, communities, political parties and the nations of the UK would be divided seriously and bitterly. It isn’t worth it. This country can be a success inside or outside the EU but it can’t prosper or be a happy place to live with ever-deeper polarisation and resentment. We need mutual respect and a degree of political cohesion to function well as a society. It’s time to accept the decision already made, understand that it can only be implemented with a lot of constraints, and move on to making the best of it.

A final consideration is that such complexity, disaffection and division would be very likely to lead to further such referendums in the future. Would it be the end of the matter, for instance, if we reversed ourselves and tried to stay in the EU, or would the campaign to leave start all over again? We could end up spending half our lives arguing about this, when making the right decisions about our education system, infrastructure, taxes and health care will ultimately be more important.

Take all these disadvantages together, and holding another referendum adds up to an alarming and highly unattractive prospect. Yet each day of confusion is now adding to the temptation for others to back it, and the call for it will steadily become an easy cry and an alternative to essential decisions that need to be made now. It would not take much for Labour to tip over into backing it, and then a majority of the Commons could quite easily clutch at this appealing straw.

There is only one effective antidote: for Conservatives to pull back from the various forms of defeating, frustrating and ousting each other. It was very clear on the morning of June 24, 2016, the day after the referendum, that we must leave the EU. It was just as clear as dawn broke on June 9, 2017, with election results in, that this would involve major compromises. Why these things should come as a surprise to anyone now is a mystery. But unless we all get over that, the case for the second vote will only strengthen — and it is a really bad idea.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2018

William Hague was the former UK Foreign Secretary.