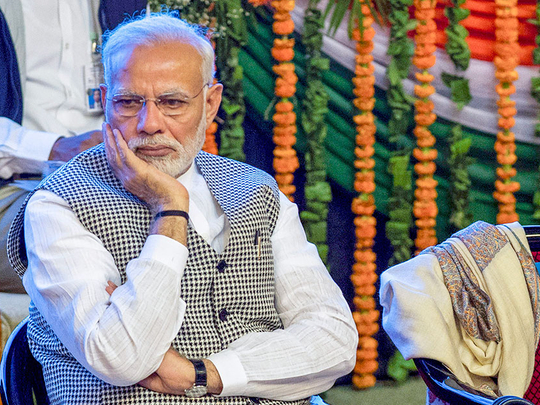

If Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi expected Karnataka to be the icing on the cake on the eve of the completion of his four years in office, he must be disappointed.

The setback in the southern state is only one of the several reverses which the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has suffered in the recent past. These include a series of by-election defeats in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, which have not been adequately compensated by the party’s successes in the northeast. That’s because electoral outcomes in the country’s heartland have a more significant impact than those in a region generally regarded as remote.

Considering that three more assembly elections are due in the next few months where the BJP is facing the anti-incumbency factor, it is evident that Modi’s fourth anniversary is not the happiest of occasions. Several things appear to have gone wrong for the prime minister and his party. Foremost is the general bleakness of the economy, where the lack of jobs and continuing agrarian distress have led to the blanking out of the phrase achhe din (good days) from the saffron lexicon.

What may have hurt the government, even more, is an intimidating atmosphere generated by a political project to virtually remould Indian society by obliterating all the supposed ignominy which the country is said to have suffered during the 1,200 years of “slavery” under Muslim and British rule. Not surprisingly, the 60-odd years of Congress rule have been included in this period of “alien” governance.

Hence, the rewriting of history textbooks and the packing of autonomous academic institutions with people in tune with the ruling party’s thinking. These have been accompanied by the veneration of the cow and the targeting of “suspected” beef-eaters.

It is this imposition of the saffron writ which made former vice-president Hamid Ansari say that the Muslims were living in fear. It also led to protests by writers, historians, filmmakers and others within the first 12 months of Modi’s rule who returned their awards. Instead of analysing their disquiet, the government and the BJP chose to dismiss them as “manufactured protests”, in Arun Jaitley’s words, and the dissatisfaction of a section which has lost the privileges. The BJP believed that it was on the right track and there was no need for a rethink.

So the government took no notice of the two open letters written by groups of retired civil servants and a third by more than 600 academics, including those in the US, Britain and Australia. While the bureaucrats expressed distress at the decline of “secular, democratic and liberal values”, the educationists regretted that not enough was done for the vulnerable groups.

There is little doubt that the government has taken many initiatives to reach out to these groups. These “small” measures have mitigated some of the ill-effects on the macroeconomic front.

Among these measures is the Jan Dhan Yojana relating to small savings by ordinary people through bank accounts. However, although nearly all the households are now said to have access to banks, the number of people with inactive accounts is embarrassingly high.

So is the case with cooking gas, where consumption has not kept pace with the higher number of households with gas connections. There have been similar shortfalls in the cleanliness (Swachh Bharat) and electrification programmes as well.

According to official figures, 72.6 million household toilets have been built since 2014, and there are now 366,000 open defecation-free villages. But in the absence of independent verification, World Bank is withholding a $1.5 billion loan.

Similarly, the assertion about the cent per cent electrification of the country has generally been taken with a pinch of salt since government data shows that there are still 31 million households without power.

Progress is visible on the highways where the construction target is raised to 45 km per day, from 27 km. The employment potential of such projects is also high. Since 100 per cent foreign investment is allowed in this sector, an estimated $82 billion is expected in the next four years.

But buoyancy from these initiatives is not reflected in the economy, as noted by a pro-Modi economist who said that the people are yet to see any material improvement in their lives. Unless this perception changes, the government will not be able to look forward to next year’s general election with high hopes.

Amulya Ganguli is a political analyst in India.