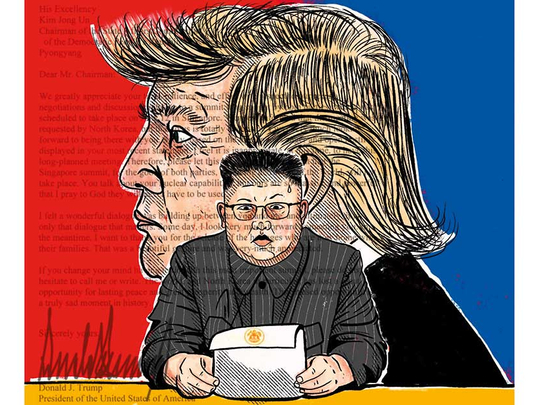

US President Donald Trump topped a diplomatic period by cancelling his summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. The previous policy of maximum economic pressure on North Korea may no longer be viable, so the risk is that Trump ends up reaching for the military toolbox.

As every president since Richard Nixon — except for Trump — has realised, the military options are too dangerous to employ. That’s even more true today, when North Korea apparently has the capacity to use nuclear, chemical and biological weapons against Seoul, Tokyo and perhaps Los Angeles. Yet Pentagon officials seem deeply nervous that Trump doesn’t realise this and has a Kim-like appetite for brinkmanship in ways that create risks of a cataclysm.

It was at least a relief that Trump, in cancelling the summit, didn’t slam the door on diplomacy. In a tone that had more of regret than anger, Trump wrote to Kim: “Some day, I very much look forward to meeting you.”

Trump apparently pulled out of the summit because of recent North Korean belligerent rhetoric, including denunciations of Vice-President Mike Pence, and because it grew clear that North Korea wasn’t planning on giving up its nuclear weapons any time soon. There was some political risk in Trump reaching a general agreement with North Korea that was much less significant and onerous than the one he tore up with Iran.

The Trump statement leaves open the possibility that South Korean President Moon Jae-in, who has been the crucial figure in the peace process, can put Humpty Dumpty together again, so that a meeting could be held later this year.Indeed, if the cancellation now leads to working-level talks between US and North Korean officials, that would be progress. The risk, though, is that we’re back to confrontation. North Korea is expected to respond to Trump’s letter in similarly measured, calm terms. But no one has ever made money betting on North Korean calmness.

North Korea could decide to create a new crisis, perhaps by conducting a missile test or an atmospheric nuclear test. If such an atmospheric test were conducted in the northern Pacific, that could send radiation towards the US and would be perceived in Washington as a great provocation. Likewise, the US could respond to new tensions by sending B-1 bombers off the coast of North Korea. If North Korea scrambled aircraft or fired anti-aircraft missiles, we could very quickly have an enormous escalation. So look out. We may be headed for a game of chicken, with Trump and Kim at the wheel. And all the rest of us are in the back seat. In any case, it will be difficult for Trump to return to his policy of strangling North Korea economically. China has already been quietly relaxing sanctions, and South Korea may not have the stomach for strong sanctions either. Kim has met with the leaders of both China and South Korea in recent months, building ties and reducing his isolation, and I expect he’ll continue the outreach to both countries.

Trump’s rhetoric didn’t particularly intimidate North Korea, but it terrified South Korea, which feared it would be collateral damage in a new Korean War. So Moon shrewdly used the Olympics to undertake a careful peace mission to bring the US and North Korea together. This was commendable on Moon’s part; he’s the one who genuinely did have a shot at the peace prize.

Denuclearisation talks

It was a mistake when Trump rashly accepted the idea of a summit without any careful preparations. The risk of starting a diplomatic process with a summit is that if talks collapse at the top, then it’s difficult to pick up at a lower level. With different aides, Trump might have pulled it off. While Trump was wrong about the possibility that North Korea would hand over its nuclear weapons any time soon, there was some possibility of a general statement about starting a dialogue about denuclearisation. North Korea would destroy some intercontinental ballistic missiles, tensions would drop, and we’d all be better off even if denuclearisation never actually happened. Yes, Trump would have been played, but the world would still have benefited from the peace process.

Yet John Bolton, Trump’s national security adviser, spoke up in ways calculated to unnerve the North Koreans, by talking about the Libya model. North Korean leaders themselves responded to Bolton’s comments with harsh, over-the-top rhetoric, including the comment about Pence. This was a major miscalculation on their part, escalating the ineptitude and helping to kill the summit. While the North Koreans didn’t get the summit they wanted with Trump, they have managed the process quite well. They used the rush of diplomacy to rebuild ties with Beijing and start discussions about economic integration with South Korea, and to moderate their international image. They’ve also created something of a wedge between Washington and Seoul, as was apparent in the response to Trump’s cancellation by a South Korean government spokesman: “We are attempting to make sense of what, precisely, President Trump means.”

In weighing the risks ahead, commentators sometimes note that Kim is rational and doesn’t want to commit suicide. Rational actors regularly make awful decisions. Both Trump and Kim would still like to make a summit happen. So we can hope for the best, but fear the worst.

— New York Times News Service

Nicholas Kristof is an American journalist, author and a winner of two Pulitzer Prizes.