Every day, about 75 people visit Penco, a stationery shop in Varanasi, although few realise that Penco is not just a shop but also a small museum of fountain pens.

Varanasi is also known as the city of temples and one of the holiest places of Hindus. Thousands of Hindu pilgrims and tourists, both Indian and foreign, pour into this city in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh daily. The most revered of all shrines in Varanasi is the Vishwanath temple on Dashashwamedh street. Because of the temple, the street remains crowded for most part of the day.

Penco stands incongruously on Dashashwamedh street — incongruously, because its both sides are lined with shops that sell garments. Penco is the only stationery shop.

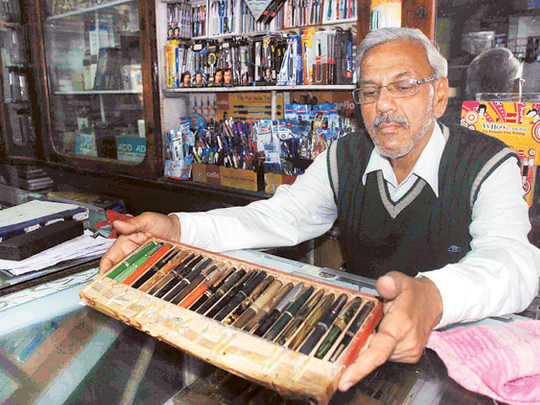

A pilgrim or a tourist, in urgent need of a pen or writing pad, rushes in to Penco and if he, by chance, is a connoisseur of fountain pens, notices the 200 rare fountain pens neatly displayed in the glass counter of the shop. Like the curator of a museum, Sheetal Prasad Sahu, the owner of Penco is always available with the details of each pen. Visiting Penco is like returning to the era of fountain pens.

The story of Penco is 67 years old, when pens meant only fountain pens and were rare and expensive. Sahu’s father, Tara Prasad, who lived in Varanasi, was unlettered and earned a living by selling fodder. He wanted to learn to read and write but then there was no concept of adult education.

So, “my father stopped selling fodder, set up Penco in 1946 and started dealing in pens”, says Sahu, who is in his fifties. “At that time only educated people bought and used pens. My father could not get an education when he was a boy but he believed that if he sold pens he would at least be able to interact and hobnob with educated people.”

Penco flourished as years passed. It was the only shop of its kind in north India. Initially only the educated and the rich visited Penco. There was a time when the royal families of Nepal, Varanasi and Rewa were loyal customers of the shop. As more schools and colleges opened in independent India and people started getting education, the need of pens rose and commoners also started flocking to Penco.

Tara Prasad sold only branded fountain pens made in the United States or Europe. When he got to know that a pen in his shop had gone out of production and would soon become rare, he would stop selling it.

Taking charge of the shop after his father’s death, Sahu continued the practice. Penco today has a collection of around 200 pens whose production stopped years ago and are considered antique.

The collection includes Parker Duofold, the first model that was manufactured by Parker; Parker 61, a pen made of pure gold; and a pen with the Tagore nib, named after Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, who was known to use the nib. The tip of the Tagore nib is adjustable — it can be made bold or fine. The other brands in the collection include Swan, Plato, Montblanc, Waterman, Sheaffer and Wearever.

‘There are other pen collectors but our collection is special because it is vast. I do not think anybody can claim to have a collection of as many as 200 rare pens,’ says Sahu.

A time came when Tara Prasad also started manufacturing fountains pens. “My father did not undergo any formal training in making fountains. He learnt the art on his own — by trial and error,” Sahu says. Tara Prasad employed a master craftsman named Bhairon Prasad Vishwakarma and brought out pens under the brands Penco and Ebonite. The latter had an unbreakable body and the ink inside it never dried up. Kamalapati Tripathi, a minister in the federal government, who hailed from Varanasi, once gifted an Ebonite pen to Indira Gandhi, the prime minister of India in the Seventies.

The pen production stopped when Tara Prasad and his craftsman died, and Sahu today rues that he did not learn the art of making and repairing fountain pens.

“Today, if a person comes to our shop with broken nib, we can replace it,” Sahu says. “We have many spare nibs. But earlier, when my father ran the shop, he would not replace the nib but try to repair it. We had a small workshop where pens were manufactured and repaired. The workshop was closed when my father died.”

But the things kept in a corner of the shop suggest the workshop still exists: a bottle of ink, a dropper, a flat, square piece of marble for smoothening the nibs, pliers, sheets of paper clipped together on which pens have been tested, and a piece of cloth stained with ink.

Times have changed. People switched to ballpoints. At present gel pens are popular. But Penco is still catering to those who love to use fountain pens. The shop continues to sell fountain pens — some are as cheap as Rs30 (Dh2) and others as costly as Rs 30,000 (Dh2,027). Even today, its clientele includes not only people from Varanasi but also from other places.

“I visit Penco at least once in a week. I have chat with Sheetal Prasad, see his collection and at times also buy a couple of fountain pens. I have seen his collection of his pens at least 100 times. I can see it another 100 times,’ says Abhijit Sinha, 40, a native of Varanasi. Sinha has been visiting Penco since he was a student.

Ashok Sharma is another loyal customer of Penco. He is settled in Lucknow, the capital of Uttar Pradesh, and always looks forward to going to Varanasi so that he can visit Penco. “And once I go there, I buy a few pens,” he says. “I have a good collection of fountain pens but they are not the rare ones.”

Some customers keep track of the fresh stocks of fountain pens through phone. “Once in a month I call Sheetal Prasad and ask him about the new pens. If I find anything interesting, I ask him to send them by post,’ says Vinay Saxena, who lives in Kanpur, a city 200 kilometres east of Varanasi.

Fountain pens had nearly vanished but now have made a sudden comeback. Rather than being a mere writing instrument, they are now considered a status symbol and a style statement.

“Earlier, I never bothered about the pen I used. But after seeing some of my seniors in my office using fountain pens, I have also started using them,” says Anand Luthra, who works as an executive in a private bank in Varanasi.

“There are customers for pens of all costs,” Sahu says. “I sell pens of the Indian brands Chelpark or Wality that cost Rs 50. I also sell Montblanc’s Meisterstuck that costs Rs 30,000.”

Nowadays, Sahu’s 28-year-old son Nishant assists him. A science graduate, Nishant could have easily studied further and got a lucrative job. But like his grandfather and father, Nishant also loves fountain pens and wants to run the shop.

“I do not want to take up any job or start a new business. I love being surrounded by pens and will continue dealing in them,” he says.

Often, Sahu receives hefty offers for the rare pens he owns. But he has always turned them down. “When people see the fountain pens displayed in the glass case, they think they are for sale,’ he says.

Once a senior executive of one of the world’s leading pen manufacturers got to know about the rare collection at Penco and visited the shop. “He was eager to have a particular pen,” Sahu says. “He said I was free to quote any amount. He wanted to display the pen at his company headquarters. But I politely refused.

He believes his pens are priceless. “You cannot exactly have a price for a thing that is no more being manufactured. Moreover, connoisseurs of fountain pens keep coming to my shop to see my collections. I want more and more people to see the pens,’ he says.

But his shop is no fortress; there aren’t any extra security measures here. “Most people do not know the value of fountain pens. Only the connoisseurs know the price. And I believe the connoisseurs are educated and cultured people. They will never try to steal a pen,” Sahu says.

Rohit Ghosh is a writer based in Kanpur, India.