A look at the big winners and losers who dominated the scene this year and are likely to remain on top of regional and international developments in 2018

Big winners

The two leaders who dominated the scene this year, and are likely to remain on top of regional and international developments in 2018, are Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman and Russian President Vladimir Putin. Both have proved they are able and willing to break both taboos and stereotypes. Tough and seemingly unstoppable, they are the names to watch in 2018.

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman

Over the past 12 months, the 32-year-old Saudi Crown Prince made world headlines. In 2017, he gave Saudi women the right to drive, curbed the powers of the kingdom’s moral police, allowed music concerts and, in his own words, “restored” moderate Islam that had eroded after the rise of Al Qaida. Politically, he jumped behind enemy lines, luring powerful Iraqi officials away from Iran, like Moqtada Al Sadr, Ammar Al Hakim, and Prime Minister Haidar Al Abadi.

Although the war in Yemen drags on and is approaching its third year, Saudi Arabia managed to yank another Iran-backed politician, former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, away from the Iranian-backed Al Houthi militia — before they assassinated him in early December. Proving his resolve, he severed relations with Qatar in June, over Qatari Emir Shaikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al Thani’s daliance with the Muslim Brotherhood and his alliance with Tehran.

Other countries followed suit, taking their cue from the kingdom, but Shaikh Tamim refused to distance himself from the Iranians, and chose neither to modify the editorial policy of the Doha-based Al Jazeera TV nor expel notorious figures from the Brotherhood, like the aging Egyptian cleric Yousuf Al Qaradawi.

Vladimir Putin

Meanwhile, Vladimir Putin was finishing off a job started by his military back in 2015, which basically focused on securing his ally in Damascus and eliminating all serious challenges the regime of Bashar Al Assad faced on the Syrian battlefield, mainly from Daesh.

He crushed the Syrian armed opposition, and forced all anti-regime politicians to abide by his rules when it came to the political process. Those who still insisted on regime change were either killed, like commander of the Islamic Army, Zahran Alloush, or dropped completely both from the UN-mandated Geneva talks, and the Astana process that Russia launched in January 2017, along with Iran and Turkey.

Over the past year his top diplomats have carefully injected Moscow-sanctioned figures into the Syrian opposition, effectively breaking the monopoly of the High Negotiations Committee (HNC).

In January-February 2018, Putin is planning to host 1,300 Syrians at the Black Sea resort of Sochi, to discuss a Russian draft constitution and possible parliamentary elections in 2018. Presidential ones won’t happen in Syria until 2021, and even then, Putin insists Al Assad can run for a fourth term.

“Putin’s strategy for Syria is not to help see that it can rebuild economically and politically,” said Professor Joshua Landis of the University of Oklahoma.

Speaking to Gulf News, he added: “Russia’s strategic position in the region will have to be undergirded by a successful economic plan for Syria.”

At this stage, however, neither the Russians nor the Iranians are willing to cough up the $226 billion – as the World Bank estimated – to rebuild Syria. That kind of money can only come from Europe and the GCC, but all Gulf countries insist they won’t help rebuild Syria if there is no serious political change that eventually leads to Al Assad’s departure.

"Putin will have to convince Western governments to buy into the revitalisation of Syria, or at least, not to block it,” added Landis, quickly noting: “This will be a hard sell.”

Senior Middle East analyst and Daesh-expert Hassan Hassan believes that in addition to its military victory, Russia’s 2017 legacy was also political. “Moscow was able to change the Turkish approach in Syria in ways that seem to favour the security of the regime in Damascus.

Russia also changed the political track that the West had itself started, through changes on the ground and politically through the Astana and Sochi process. There will be security and military challenges for the regime for many years to come. I don’t think they will disappear anytime soon, and its hard to predict what could happen as a result of continued conflict in the coming year.”

The Russian Defence Ministry claims that 85 per cent of Syrian territory has been liberated from Daesh, but it makes no mention of entire towns and cities east of the Euphrates, like Al Hassakah and Al Qamishli, presently dotted with US troops and Kurdish fighters from the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

It also says nothing of Idlib in the Syrian northwest, firmly in the hands of the Turkish Army, along with Jarablus, Azaz, and Al Bab in the Syrian north. And finally there are pockets throughout the Damascus countryside, still held by the armed opposition in Al Ghouta, the agricultural belt surrounding the Syrian capital.

None of the parties in control of these cities and towns have shown the slightest indication of wanting to leave. Nor, of course, have the Iranians, who helped take the city of Al Mayadeen in the countryside of Deir Al Zor, or Hezbollah, which is firmly entrenched in the Qalamoun mountains, on the Damascus-Beirut Highway, and near Shiite shrines in Damascus.

By announcing that he was withdrawing excess troops from Syria in December 2017, Putin hoped that this would trigger a domino effect among all stakeholders, and that they would start evacuating as well.

This is easier said than done, however. The Turks have been in-control of three border cities since the summer of 2016. They are providing them with infrastructure and electricity, hoping to use them as a security zone, to expel Daesh and the Kurds from their borders, and eventually, to relocate many of the 3 million Syrian refugees residing in Turkey since 2011.

The Jordanians are planning to carve out a safe zone along their border with Syria, with both Russian and US support. The aim this time is to keep Hezbollah — rather than the Kurds — away from the border, along of course, with the Daesh-affiliate there, known as the Khaled Ibn Al Walid Army.

Already 1,000 Russian military police are monitoring the ceasefire in southern Syria, from the border strip to the countryside of Suwaida in the Druze mountain. They are making sure that “no foreign fighters” remain — only Syrians from both sides of the war. Both have been stripped of their heavy arms, and neither tanks nor warplanes will be allowed into this ‘de-escalation zone’, which officially, will be returned to the regime. Similar agreements were made last year for territory north of Homs and east of Damascus, both manned now by Russian troops.

Losers of 2018

Daesh

Once feared around the world, controlling territory the size of Britain, Daesh is now all but finished, having been expelled from all major cities it once controlled, like Mosul, Al Bu Kamal, Deir Al Zor, and Al Raqqa. Pockets of Daesh sympathisers still emerge in conflict zones throughout Syria and Iraq, but the organisation is finished.

The Syrian opposition

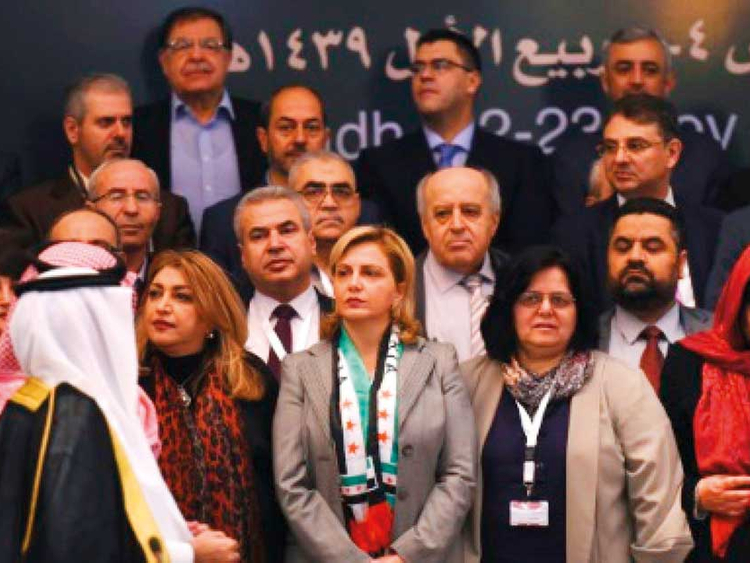

At their latest conference in Riyadh, the Syrian opposition agreed to several painful concessions, at the request of the Russians. First, they expanded their delegation to the peace talks, breaking the monopoly of the HNC and then removed their chairman Riad Hijab, along with eight top officials, ostensibly because they were too tough on compromise with Damascus.

At the final communique of the Riyadh Conference they said that Al Assad’s departure was a goal, rather than a precondition. Even that was scoffed at by Damascus and Moscow, saying that Al Assad’s fate should not be up for discussion. If they don’t agree, they might get excluded from the Sochi talks and whatever agreement is reached there.

Qatar

Doha tried to project itself as the problem solver for all conflicts, often getting in bed with the groups that were the source of all anguish – Al Qaida, the Brotherhood, Hamas, Iran, and Daesh. It tried to outsmart all players in the Middle East, thinking that it could continue to buy off support with its excess wealth. That strategy backfired after its standoff with the Quartet since last June.

Their influence in Gaza has all but withered, thanks to a joint effort by Egypt and the UAE. In Syria, their proxies in the battlefield have been destroyed by Russia while in Lebanon, Hezbollah was forced to reach a power-sharing formula with the Saudi-backed premier Sa’ad Al Hariri.

Desperate for regional support — and legitimacy — Al Jazeera is now playing the Jerusalem card, hoping that by trumpeting the Palestinian cause once again, it can add some appeal to Qatari foreign policy — at least in Arab eyes. So far, it has not worked, and likely won’t in 2018.

Iran

When it entered the Syrian conflict in 2012, many expected Iran to try and control all of Syria. Over the next three years, entire stretches of land were lost to the armed opposition, despite Iranian presence in the battlefield, forcing the Russians to intervene in 2015.

Since then, Iran’s role has been greatly reduced. Its sphere of influence has been restricted to three pockets only: in the Qalamoun mountains, on the Damascus-Beirut Highway, and within the capital. Iran tried to send military police to help patrol both Idlib and Al Ghouta, but both suggestions were vetoed by the opposition and the Russians as well.

Iran tried to relocate 10,000 Shiites from northwestern Syria in the belt around Damascus but that too never materialised. Although it was part of the Astana process that started in January 2017, Iran has ostensibly been left out both from the Geneva talks and the forthcoming Sochi process of 2018.

US President Donald Trump agreed to let it happen, during his November meeting with Putin, on the condition that Iran is kept in the cold. At best, they will be invited as an observer, but certainly not as a decision-maker or guarantor as it had been at Astana.