Salt, Jordan: The reversal last week of a deeply unpopular tax law appeared to defuse days of mass protests in the Jordanian capital, Amman, but out in the provinces, Rami Fawri was not impressed.

“Are we supposed to clap?” asked Fawri, a 40-year-old owner of a stationery shop in Salt, a hilltop city west of Amman. “They want me to forget what they did to me before? No, I remember, I remember the prices went up. We are suffocating.”

Jordan is known for its relative stability in an often-tumultuous region, and US officials looked on with concern last week as this key Middle Eastern ally faced its largest street protests since the Arab Spring unrest of 2011.

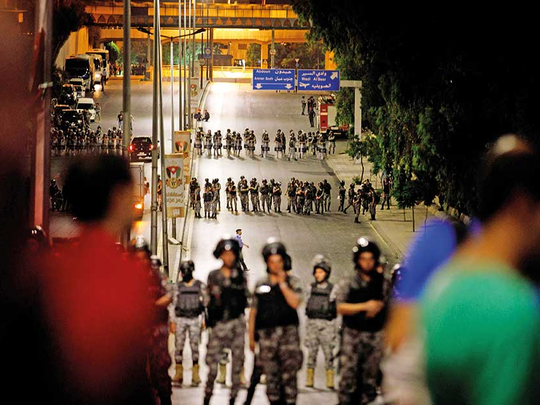

The introduction of the new tax law proved too much for many Jordanians struggling with price hikes amid stagnant economic growth. Demonstrations that had been bubbling in provincial cities like Salt for months spread to central Amman, drawing a wide cross-section of Jordanians. They chanted for the prime minister and his government to be sacked and for the law to be reversed, and they got it.

But while Jordan’s King Abdullah appears to have averted an immediate crisis, he faces a difficult road ahead as he balances the need to address the country’s economic woes with the demands of an emboldened population.

“People have discovered that they have power which they didn’t know they had before,” said Labib Kamhawi, a prominent political analyst and government critic.

Jordan is embarking on a three-year programme of painful economic measures ordered up by the International Monetary Fund to help the kingdom cut its yawning public debt. In Salt, demonstrations began in February after the government eliminated subsidies on bread, doubling prices.

Living costs in Jordan are already among the highest in the Middle East, and incomes have not kept up. Unemployment is at 18 per cent. Fuel prices are more than 50 per cent higher than in the United States.

Adding to the economic stress are at least 650,000 recent Syrian refugees, on top of a population that includes millions of Palestinians whose ancestors were displaced from their homes long ago.

Largely devoid of natural resources, Jordan survives in large part on handouts. While the Trump administration has slashed aid elsewhere, the United States has pledged more money to Jordan, which shares a 150 mile-long border with Israel and is a hub for thousands of US troops.

Ordinary Jordanians complain they have become the country’s new chequebook through their taxes, while graft and fiscal waste are allowed to continue among the political elite.

In the short term, all eyes are on the new prime minister Omar Razzaz, a Harvard-educated economist who previously worked for the World Bank and most recently held the position of education minister.

His first move, shelving the tax law, pleased the street, but the next hurdle will be choosing a cabinet acceptable to the public. “We don’t want the same faces, these rotating chairs,” said Jreabea.

Political analysts say many Jordanians have been restrained about criticising the monarchy outright or upsetting the political status quo because they fear the kind of anarchy that has wracked neighbouring Syria and nearby Yemen, which have been devastated by civil wars. But hunger can mean people feel they have less to lose, Kamhawi said.

“Will Jordanians tolerate all of this poverty in return for not having chaos like Syria and Yemen?” asked Mahmoud Al Dabbas, a sociologist based in Salt. “People don’t want to lose everything.”

But he said the mood is changing in cities like Salt. While demonstrations have ebbed in the capital, they have continued on a smaller scale outside. They lack any clear leadership structure, making them more likely to spin out of control, analysts say.

Standing with his two-year-old daughter atop his shoulders at a protest in central Amman, Mohammad Herzala, a 39-year-old furniture store owner, said his only demand was to be able to support his family.

In front of him, the crowd chanted exuberantly. Men raised their hands in time with a drumbeat.

Herzala said he brought his children to the demonstration because “I want them to know how to ask for their rights.”