BAGHDAD: The two Turkish men shuffled into the courtroom, their closely cropped hair, clean shaven faces and chubby waistlines hardly the look of fearsome fighters of Daesh.

Appearing in court for the first time since being arrested in August on charges of belonging to Daesh, they professed their innocence, telling the judge they were simply plumbers who migrated to Iraq from Turkey looking for work.

After an 18-minute trial, they were sentenced to death by hanging.

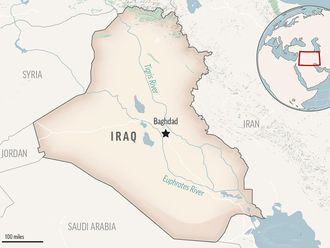

The men are among hundreds of foreigners detained in Iraq on terrorism charges after the toppling of Daesh’s self-declared caliphate. The defendants — men, women and children hailing from Asia, Europe and Africa — are coursing their way through Iraq’s criminal justice system, receiving harsh sentences in rapid-fire trials.

The trials and capital sentences are presenting foreign governments with a moral and political dilemma. Do they object to the Iraqi trials and claim their citizens, who could threaten their home countries and radicalise others if repatriated? Or should Iraqi courts be allowed to determine the defendants’ fate in trials that human rights groups and the United Nations say are deeply flawed?

The issue has taken on a new urgency as major combat against Daesh ended this month. Iraq has fast-tracked executions under the year-old orders of Prime Minister Haider Al Abadi, aiming to “give comfort to the families” of Daesh’s victims.

Iraq’s justice ministry has disclosed 194 terrorism-related executions since 2016, including at least 27 foreigners from other Arab countries, according to a review of ministry news releases.

Last week, the ministry said it had executed another 38 prisoners on terrorism-related charges, but it did not specify their nationalities, prompting a rebuke by the United Nations human rights office. At least one of those executed had Swedish citizenship, researchers into human rights and terrorism said.

Up to 6,000 more are on death row and their nationalities have not been disclosed, according to the United Nations. Many more suspected militants are in custody, including at least four Europeans.

European countries have given little indication that they want to claim their citizens.

In a statement, Turkey’s foreign ministry said it is aware of their citizens being detained in Iraq for allegedly joining Daesh. “We are in touch with the Iraqi authorities in terms of finding out their whereabouts and ensuring their repatriation,” the statement said.

The United Nations said last month that Iraq does not have jurisdiction to try Daesh atrocities and that Iraqi investigators, prosecutors and judges do not have the capability to ensure due process. It urged Iraq to turn to the International Criminal Court for such cases, especially ones dealing with the attempted genocide of minority groups like the Yazidis whose reintegration into Iraqi society largely depends on the accurate prosecution of crimes committed against them.

Iraq’s massive dragnet is ensnaring scores of innocent people, while rushed investigations and trials are failing to distinguish between Iraqis who embraced Daesh and others who cooperated with the group out of fear or coercion, human rights groups and the United Nations said.

Abdul Sattar Bayraqdar, a senior Iraqi federal judge, bristled at criticism, saying his country’s judges and lawyers have sacrificed their lives to guarantee fair trials and hold terrorists accountable. He said since 2003, at least 60 judges and more than 160 investigators and court employees have been killed in terrorist attacks stemming from their work.

As for foreigners affiliated with Daesh, Bayraqdar said crimes committed by extremists on Iraq’s soil must be prosecuted in Iraq, and it is under no legal obligation to hand over suspects or convicts to other countries.

“But those who are acquitted are being handed over to their countries,” he said.