Along the borders of Niger, Libya, Algeria, Burkina Faso, and Mali close to three million traditionally nomadic people sit dispersed and divided by frontiers and wars. These Berbers and nomadic pastoralists call themselves Kel Tamasheq, or speakers of Tamasheq, but are more commonly known as Tawareq.

- Ag Al Hussaini | Guitarist

It is believed the Tawareq people emerged coalescing around Tin Hinan, a Berber queen who lived in the 4th or 5th century. The Queen’s influence on the social fabric of the tribe can even today be seen in how the Kel Tamasheq organise their communities and interact with each other.

The matriarchal nature of their society is seen in how families trace their lineage, through their mothers, all the way to the Queen herself, and how men, and not women, wear full face veils.

Sounds from the Sahara

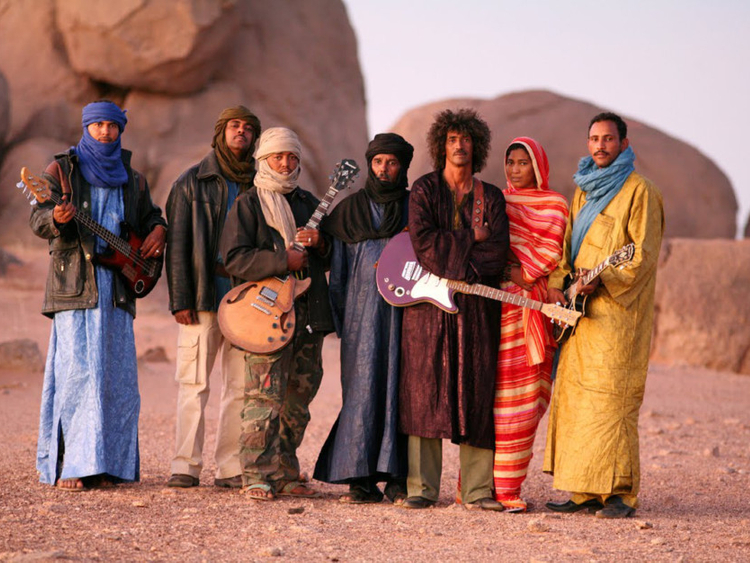

And members of one band have become international campaigners for the plight of the Tawareq people. The story of the now internationally-acclaimed group, Tinariwen, which translates to the People of the Desert, began in 1979, between a refugee camp in Tamanrasset, in southern Algerian, and late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi’s Tawareq training centres.

In the refugee camps, exiled musicians performed at weddings and community festivals with homemade guitars and percussion instruments made of jerrycans.

On the Libyan side, after gruelling days of training, musicians spent their downtime writing music, and recording it on cassette tapes. Their songs reflected the plight of the Tawareqs. The musicians dreamt of a homeland in northern Mali. Not only did their songs describe the fight, but their music also fuelled and encouraged it.

Tinariwen, which translates to “people of the desert” in Tamasheq, narrates the Tawareqs’ two-step approach for a homeland. With Tinariwen’s desert blues, there is no need for a Tamasheq translator. Nomads even in their music, Tinariwen members play with rock, folk, gnawa, blues, and traditional Berber sounds to create unique rhythms. The sounds of exile, sorrow, longing, and violence from a generational struggle are evident with every strum of the guitar and every thump of the bass. The rawness of their sound is a testament to the pain they carry into every studio and onto every stage.

The Tawareq are the guides of the Saharan merchant routes. All the way up to the French occupation of Algeria and Mali, in the 19th and 20th century, the Tawareq used their deep knowledge of the desert to transport people and goods to and from the northern and western coasts of Africa. Along the way, they played a pre-eminent role in the construction of historical sites in Timbuktu, Gao, Kidal, and other desert cities across Mali, Niger, and southern Algeria.

Path to exile, rebellion, and loss

Despite longstanding promises and agreements, French administrators confiscated pastoral lands and obfuscated transport routes. The Tawareq were outnumbered, outgunned, and forced to flee their land. The hope for an independent nation of Azawad – the imagined Tawareq nation – was reneged on, and the Tawareq began a symbolic, political and physical exile that continues to this day.

After decolonisation, it was the governments of Sahelian Africa that became the targets. The first Tawareq rebellion targeted the young Malian nation in 1963. The response was violent; thousands were imprisoned or sent fleeing to refugees camps in Algeria. In exile, an organised insurrection began.

In the late 1980s, armed and sponsored by Gaddafi’s revolutionary regime, hundreds of young men were urged to join an armed movement against the government in Mali. Gaddafi’s training camps were the nexus of nationalistic hopes, tough soldiers, and sounds that would soon ring across the world.

In 1992, the Gaddafi-trained armed Tawareq rebellion brought the Malian and Nigerian governments to the table. Although political concessions allowed thousands to return to northern Mali and Niger, the peace was short-lived and conflict would return for the next two decades. Over this time, tribalism, factionalism, and conflicting views on how to take the fight forward dogged the Tawareq movement.

In 2012, after the fall of the Gaddafi regime, many of the Tawareqs who were trained in Libya, brought stashes of weapons and decades of battle experience to Northern Mali. The powder keg in Libya sparked a more intense and ideologically-driven fight that created a two-headed monster in Northern Mali. Dogmatic, angry, and coopted by Islamist factions, the Tawareq struggle became one of the vehicles for an Al Qaida-inspired Islamist state in Northern Mali.

Splintered, divided, and infiltrated by violent extremists, the promise of a Tamasheq homeland now seems elusive. In recent months, Tawareq political factions have begun to work with the Malian government to find room for autonomy and decision-making in the Sahara. Above all, compromise and dialogue are on the menu as the Tawareq crave calm and unity.

Military artistes

And so, Tinariwen, after winning the Grammys, making friends with U2’s Bono, Coldplay’s Chris Martin, and Radiohead’s Thom Yorke, and touring to sold-out shows, remains battle ready. One of the guitarist, Abdullah Ag Al Hussaini told an Algerie News journalist: “We are military artistes! Today, if we see that our brothers need fighters rather than musicians, we will go to the front, because we are always ready to answer the call of the preservation of our land, our values, and our culture. This is what we do through music, and we will do it again with arms!”

Tinariwen’s is the story of the Tawareq. A nomadic people who refuse to be boxed into one nation, one genre of music, or one story ending – until the final note, the rebellion continues in exile and in sound.

Tarik Chelali is a Gulf News contributor on North Africa.