WASHINGTON/Moscow

The spurious story line alarmed Americans. It spread like wildfire, distorting facts into outlandish fictions, despite being attributed only to obscure sources. And it inflamed already divisive politics before the US government concluded — perhaps too late — that it was a Russian disinformation campaign.

“We would take any misinformation like that very seriously,” Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the White House press secretary, told reporters at a briefing on Monday.

Sanders was responding to a question about how the Trump administration would view a “disinformation campaign by a foreign government” — specifically, fabricated and sensational news distributed by Moscow in the 2016 election. But presidents have for decades dealt with the phenomena of Russian-peddled fake news, if under a different name.

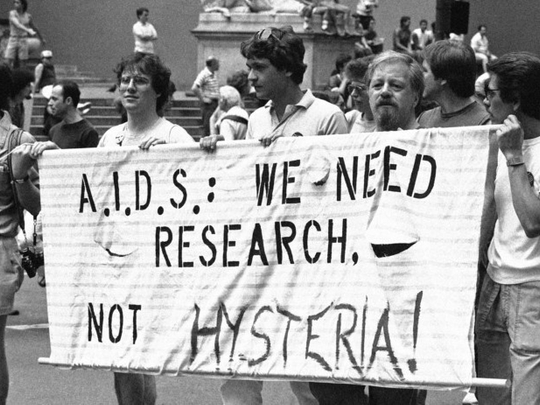

It is rooted in a Cold War plot that fanned a conspiracy theory about the origins of Aids, earning a rebuke from the Reagan administration, and now serves as a lesson about Russian disinformation and the subversion of weighty issues worldwide.

“Today, the fingerprints of Russian disinformation campaigns have been left on both sides of the Atlantic,” Mark R. Jacobson, a professor at Georgetown University and former Pentagon adviser, told a congressional hearing in November.

“Whether it is ‘Brexit’ or the American election, Russian propaganda still infects US social media networks,” Jacobson said. “And we see the same sort of divisive propaganda that we saw during the Cold War.”

Called Operation Infektion by the East German foreign intelligence service, the 1980s disinformation campaign seeded a conspiracy theory that the virus that causes Aids was the product of biological weapons experiments conducted by the United States. At the time, the disease disproportionately afflicted gay men, and the Reagan administration’s slow response had escalated into suspicions in the gay community that the US government was responsible for its origins.

“The KGB picked up on that, and added a new twist with a specific location: Fort Detrick, Maryland,” where scientists conducted biological weapons experiments in the 1950s and 1960s, said Douglas Selvage, project director at the Office of the Federal Commissioner for Stasi Records in Berlin.

The KGB campaign began with an anonymous letter in Patriot, a small New Delhi newspaper that was later revealed to have received Soviet funding. It ran in July 1983, under the headline “Aids May Invade India: Mystery Disease Caused by US Experiments” and pinned the origin of the disease to Fort Detrick.

Playing on human psyche

The choice of Patriot was deliberate, said Thomas Boghardt, a military and intelligence historian who traced how the campaign unfolded. “It had no explicit links to the Soviets and was an English-language newspaper easily accessible to a global audience.

“The Soviets intuitively understood how the human psyche works,” Boghardt said. He said the playbook was simple but effective: Identify internal strife, point to inconsistencies and ambiguities in the news, fill them with meaning and “repeat, repeat, repeat.”

A September 1985 memo to Bulgarian intelligence from the East German secret police served as a conduit. The disinformation campaign aimed, according to the Stasi, “to generate, for us, a beneficial view by other countries that this disease is the result of out-of-control secret experiments by US intelligence agencies and the Pentagon involving new types of biological weapons.”

A month later, the Soviet journal Literaturnaya Gazeta published a paper titled Panic in the West or What Is Hiding Behind the Sensation Surrounding Aids. It included accurate information about the disease and Fort Detrick but cited the Patriot letter to connect the dots.

The paper received international attention and its allegations were repeated around the world.

The same tactics have shown up in recent years.

Birtherism, the homespun conspiracy theory that President Barack Obama was not born in the United States, was picked up by Russian state news media and then cited by right-wing groups. The so-called Pizzagate scandal, the baseless allegations that John D. Podesta, the chairman of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, abused children in a pizza restaurant, was similarly amplified by Russia accounts.

Selvage said those conspiracy theories would have thrived on their own, even without Russian agitation. He said foreign information warriors simply exploited optimal “operational environments.”

Jacobson likened the Aids campaign to fake Russian accounts and campaigns like Blacktivist and Black Fist that exploited the Black Lives Matter movement and heightened racial tensions in 2016.

Exploiting divisive issues

The Twitter bots that helped spread viral fake news during the election last year have now morphed into cyborgs, or accounts that blend automation with human curation, said Samantha Bradshaw, a researcher on the Computational Propaganda Project at Oxford University. They are more difficult to identify, but still latch onto divisive issues and seek to deepen the wedge.

“The point is not to just tell a lie, but to tell a lie in increments,” Bradshaw said.

She pointed to the first case of social media disinformation, when Twitter and Facebook users lobbed theories about the disappearance in 2014 of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370. Rumours of its fate included a natural disaster, Ukrainians trying to assassinate President Vladimir Putin of Russia, and a lost and confused Second World War battalion emerging to shoot down the plane.

“This was not to convince people about the World War II battalion but telling them to distrust the media because they can’t get the story right in the first place,” Bradshaw said.

— New York Times News Service