As Mexico emerges from the most violent election campaign within living memory and embarks on the presidency of Andres Lopez Obrador, one prominent citizen watches at a diagonal: a veteran of Mexico’s other war — not that over narco-traffic and its clients in politics, but that against nature.

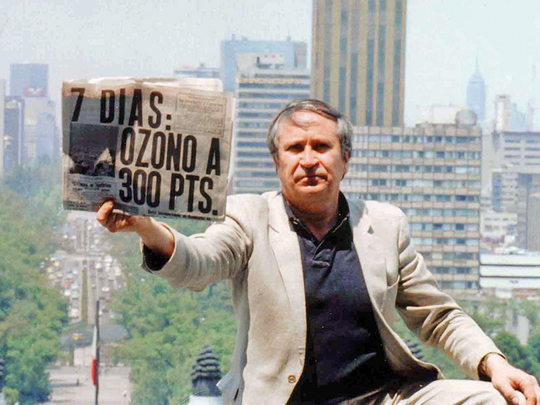

In a recent interview with the daily El Universal, Homero Aridjis — award-winning poet and former ambassador — described all the candidates at last June’s election as “environmental illiterates” — referring to the battle he has fought for decades now, and which he sees reaching its final stages — for Mexico’s natural and cultural heritage.

His war is fought for the survival of such menaced species as the unique richness of butterflies in her forests, turtles along her coastlines, whales in her waters.

The great strength of Aridjis’s work is the faith it transmits in a creative virtue of the world … and in the possibility of saving it.”

- -JMG Le Clézio, Nobel laureate

Such matters, however urgent, were “outrageously absent” from debate or discourse before or after the election, thunders Aridjis in conversation — the man who, more than any other person in Mexico, is responsible for the continued existence of these still threatened, marvelous creatures, and many others. “I don’t know whether it is indolence or ignorance among those who govern us,” he told El Universal, “but it is a grave act of moral corruption.”

Lopez Obrador will assume the presidency amid “an environmental disaster”, says Aridjis. “One of contaminated seas, lakes and rivers, terrible deforestation which has worsened of late, threats to — and trafficking in — fauna ... and in the capital, monstrous pollution. None of the candidates expressed any interest in these problems of vast importance.”

Aridjis defies categorisation. After the death of his friend Octavio Paz, Aridjis, now 78, became Mexico’s most important poet — of verse at once mystical, personally intimate and romantic. The author of 49 books of poetry and prose, he was the country’s ambassador to Switzerland, the Netherlands and Unesco. And Aridjis founded the “Group of 100” artists and intellectuals in 1985 to lead and coordinate what has since been an unrelenting fight for nature and indigenous peoples, a battle during which he has “almost lost count”, he says, of the death threats against himself and his family.

Now, as Mexico’s political violence spirals and narco-bloodletting hurls the country into an abyss apparently without bottom, a visit to Aridjis at home in Mexico City is like a corrective to the madness, a reminder of what matters on a higher level — that of his higher causes.

Not that Aridjis’s struggles for imperiled flora and fauna put him “above all that” — on the contrary. His foremost message to the incoming president is: “What will happen to the thousands of unresolved justice cases — crimes committed by the cartels, daily murders, femicides, acts of corruption — that the Pena Nieto government has accumulated during these six years? Since his inauguration in 2012, there were some 107,000 homicides, among them 42 journalists whose murders are unresolved. Will there be honest justice, or will the victims be buried by the opportunistic gravestone of forgetfulness in that electoral circus?”

To enter Aridjis’s house is like stepping into a wonderland past. The walls are lined with masks Aridjis has found on travels around his native land, ensnared “before the New York art dealers get their hands on them!” he says, eyes wide. They come from Oaxaca, Michoacan, Chiapas, used in dances of the Catrines, the Viejitos, Moors and Christians, Cora and Yaqui — so that all we discuss has the stare of ancients upon us. Aridjis exudes a mixture of sagacity, strength and charm; his energy for a man two years short of 80 is infectious.

Aridjis’s odyssey (an analogy he enjoys, given his name and Greek ancestry) began in childhood, with a near-fatal accident when 10-year-old Homero injured himself with a shotgun lent to an older brother. The convalescent boy felt his own survival “connected” to that of birds the gun was intended to shoot.

But Aridjis’s collateral, his gravitas, rests upon decades of work for the natural backdrop against which these horrors unfold.

Aridjis hails from Contepec, a town nestled against the Cerro Altamirano in Michoacan, in central Mexico, where — for millennia before the region became infamous as terrain over which drug cartels battle — millions of monarch butterflies converged from southeastern Canada and the northern United States to overwinter. This wonder infused young Aridjis’s poetry; he described the monarch as a “winged tiger”.

In 1975, this miracle was “discovered” by Canadian scientists: a use of the word which Aridjis likens to the “misnomer” of Cristoforo Colombo discovering, in 1492, an entire hemisphere that had been civilised for millennia. Aridjis and his Mexican forebears knew of the “millions of butterflies, layered like tarnished gold on the trunks and branches”. Because it occurs in early November, Indian lore connects their arrival to the return of departed souls on the Day of the Dead.

The Group of 100 had been initially formed to combat lethal pollution in Mexico City, but later focused on the menaced future of the butterflies, facing a new threat: logging, both sanctioned and illegal. A battle began to save “the landscape of our childhood and the backdrop of our dreams, from the depredation of our fellow men”, as Aridjis told a joint symposium of Unesco and Pen International (of which Aridjis was international president for six years), in the hope that “perhaps other human beings can save their hill and their butterfly, and all of us together can protect earth from the biological holocaust that threatens it”.

In 1986, Aridjis convinced then president Miguel de la Madrid to create the Monarch Butterfly Special Biosphere Reserve. However, fires and unchecked cutting proceeded apace in the reserve and in 1989, “the butterflies came to Altamirano, but did not stay”. The reserve challenged “political interests, local and national”, explains Aridjis, “with congressmen, mayors and ejidatarios — co-owners of common land — logging on sanctuary land”. Throughout the 1990s “the government continued to allow logging in both unprotected and protected areas — illegal and commercial cutting were rampant”.

But in 2000, the protected area was tripled, and in 2008, with Aridjis now Mexico’s ambassador to Unesco, the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve was listed as a world heritage site. Even so, with narco-trafficking cartels now controlling the power players in Michoacan, “illegal cutting, illegal fires continue,” says Aridjis. “Often the cartels and the logging interests overlap, joining hands, becoming one and the same.”

By the 2013-2014 season, the monarch population had plummeted from 1.1 billion butterflies overwintering in central Mexico in 1996 to 33 million. Aridjis and monarch scientists Lincoln Brower and Ernest Williams penned a letter, signed by more than 200 writers and scientists from 18 countries, to US president Barack Obama, Pena Nieto and Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper, identifying a further cause for the decline as “genetically modified herbicide resistant soybean and corn crops in the US corn belt. Relentless spraying of glyphosate herbicides on the fields has destroyed the once abundant milkweed plants, the only plants that monarch caterpillars can eat.” The letter urged action to preserve the migratory phenomenon, pleading that “the monarch butterfly is literally being starved to death”.

“I wonder whether Donald Trump will take any interest in the monarchs,” wonders Aridjis now, “or will his scorn for migrants extend to migratory species as well? For now, the butterflies come — but for how much longer?”

A Seri person told him that when a member of the community dies, he or she turns into a Leatherback turtle, and Seri elders are said to be able to talk to them. “Obviously,” says Aridjis, “the Seri don’t eat leatherbacks, but both may become extinct.”

During the 1970s, while Aridjis was Mexico’s ambassador to the Netherlands, he forwarded letters to the president protesting against the cruel mass slaughter of sea turtles, who are facing extinction, on the coasts of Mexico. “I only provoked his anger,” says Aridjis. “He thought it frivolous of me to be defending turtles when there were more important matters in hand, such as selling Mexico’s oil, uranium and natural gas.”

“What kind of economic progress,” he adds, “cripples ecosystems and makes the land barren and unlivable?”

The narrative unearthed by Aridjis and his movement was one of shocking cruelty against species which Aridjis calls “living receptacles of the earth’s natural history”. They survived the extinction of dinosaurs but are threatened by the banalities of greed for turtle “products” — their skins, shells and supposedly aphrodisiac eggs.

In articles for the newspaper La Jornada, Aridjis revealed that pirates, unheeded by navy patrols, severed the front and rear flippers of captured turtles before throwing the still living creatures back into the sea. At Mazunte, Oaxaca, olive ridley turtles “piled up like boulders” were killed with bullets or machetes. “Often the womb would be slit open to extract eggs and the turtle left to die a slow death on the sand.” Mutilated females whose wombs were ripped open at sea “frequently crawled up on the beach to die ... Near one beach was a mountain of carapaces 80 feet high ... Every restaurant had turtle eggs on the menu.”

Although the sale of turtle eggs was forbidden, a collection and distribution network continued to operate. Poachers crammed up to 1,000 eggs into a single sack, often “accompanied by the same marines charged with guarding the nests”.

In 1990, after reading a published declaration by the Group of 100, then president Carlos Salinas de Gortari signed a total and permanent ban on the capture of sea turtles. But 28 years later, says Aridjis, “we lack the means to enforce it, and there are other threats: incidental capture of turtles in commercial fishing gear, the BP Alabama oil spill, entanglement in and ingestion of plastic debris”.

In 2004, two veterinary students studying olive ridley turtles disappeared — the body of one later washed ashore; the death certificate registered death by beating, not drowning. No one — certainly not Aridjis — would suggest that Mexico’s wars are not interconnected.

A wonder of the natural world occurs in this lagoon on the coast of Baja California. After completing one of the world’s longest migrations undertaken by any mammal — between 5,000 and 6,800 miles — magnificent gray whales spawn their young, returning each March with their calves to the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas. The warm lagoon waters were officially protected by legislation in 1954, 1972 and 1979.

Mexico established a gray whale sanctuary in Laguna San Ignacio in 1954 and banned whaling. That same year Exportadora de Sal, SA was founded, to mine salt in Baja California Sur. In 1972 the lagoon was decreed a reserve and refuge area for migratory birds and wildlife, and in 1979 a refuge for pregnant whales and calves and a tourist attraction area.

But in 1995, Aridjis was notified by an American student of a plan by Exportadora de Sal, the largest solar salt-producing company in the world which is 49 per cent owned by Mitsubishi and 51 per cent by the Mexican government — for a new industrial salt production installation. The plant would produce a further 7ms tons of salt, engulfing 116 square miles of tidal flats and mangroves — plus a mile-long pier that would also seriously endanger the whales.

Aridjis and the Group of 100 took the offensive, denouncing the company’s 465-page environmental impact assessment that contained only 23 lines on whales and “denies the existence of any body of water that would be adversely affected by the saltworks’ operations”. “Protected areas,” said the group, in a full-page advertisement in the New York Times signed by Octavio Paz, Allen Ginsberg, Margaret Atwood and Gunter Grass among others, “would become evaporation ponds, pumping stations, conveyor belts, stockpiles, new service roads and new human settlements ...”

The now international campaign — coined the biggest environmental battle ever in Mexico — paralleled those seeking to ban Japanese and Norwegian whaling.

In March 2000, five years after the campaign was launched, then president Ernesto Zedillo annulled the saltworks project, citing harm to the landscape, although the real reason was financial. In conversation, it is one of the few victories Aridjis allows himself to savour without qualification: “It is one of my great joys to go there, to watch and touch the whales, meet local people I came to know, who are bringing up their children to love the whales.”

Aridjis’s articles and speeches were recently collected and translated into a book, News of the Earth. The Nobel laureate JMG Le Clezio writes of the volume that “the great strength of Aridjis’s work is the faith it transmits in a creative virtue of the world, pessimism notwithstanding, and in the possibility of saving it”.

In his preface, Aridjis writes that he “often felt like Sisyphus, confronting the same problems over and over again, or Cassandra, prophesying disaster, or Don Quixote, because we sometimes seem like madmen tilting at windmills”.

Relevant to the election result: the book records how the party of the favourite to win, Andres Lopez Obrador, was as obstructive towards Aridjis’s campaigns over butterflies and whales as either of the two establishment parties Obrador claims to usurp.

Aridjis is darkly, disdainfully hilarious about the banal vulgarity at play in the encounters his campaigns have led him to. He recalls a president’s relative offering him a car and a chauffeur to stop campaigning against a chemical waste plant. And that at the 1994 International Whaling Commission meeting in Puerto Vallarta, the undersecretary of fisheries offered him a $50,000 bribe to stop opposing Mexico’s support for Japanese whaling.

Then there was a meeting with the owner of the influential Televisa stations who, to Aridjis’s amazement, offered his support for the campaign against Norway and Japan: “I don’t give a damn about environmentalism,” he said, “but I love going out in my yacht and watching the whales swim around.”

Phone numbers for the Japanese and Norwegian embassies were duly broadcast on Televisa’s channels and viewers asked to call demanding an end to whaling. Salinas de Gortari took note and instructed the undersecretary to get the new Mexican position from me.

“A corrupt journalist once said to me: ‘I don’t understand you, Homero. You have access to all these powerful people, and could really get yourself a good deal — money, a position. And all you talk to them about is stupid animalitos and arbolitos. I told him I don’t think of my work as being for stupid little animals or little trees. I think of it as being a battle for who we are, and the existence of what we have inherited from nature”.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd