Kip Moore, a country music singer-songwriter with hits like Running for You and Hey Pretty Girl, has had some disturbing experiences with fans lately.

At some shows, women have approached him demanding to know why he stopped chatting with them on Instagram or Facebook. Some said they left their husbands to be with him after he said he loved them. Now they could be together, the women told him.

“They’re handing me a letter, you know, ‘Here’s the divorce papers. I’ve left so and so,’” Moore, 38, said. “If I check my inbox right now, I’d have hundreds of these messages. But I try not to check it, because it disheartens me.”

Moore, fuelled by his country music fame, is a victim of what has become a widespread phenomenon: identity theft on social media. Recent searches found at least 28 accounts impersonating him on Facebook and at least 61 on Instagram. Many of the accounts send messages to his fans promising love and asking for money. Those who get duped often direct their anger at the real Moore.

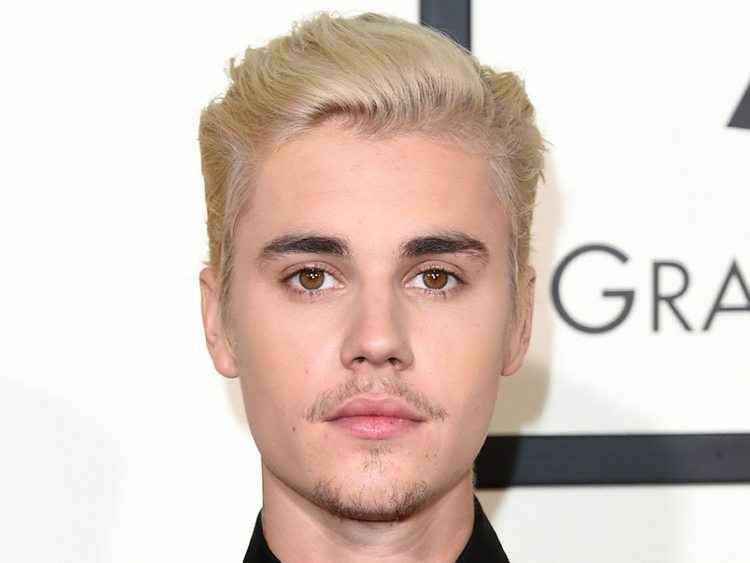

The issue of fake social media accounts masquerading as public figures is acute. Facebook, Instagram and Twitter teem with accounts that mimic ordinary people to spread propaganda or to be sold as followers to those who want to appear more influential. But millions of the phoney profiles pose specifically as actors, singers, politicians and other well-known figures to broadcast falsehoods, cheat people out of money — or worse. Last year, Australian authorities charged a 42-year-old man with more than 900 child sex offences for impersonating Justin Bieber on Facebook and other sites to solicit nude photos from minors.

In a video last year, Oprah Winfrey warned her Twitter followers that “somebody out there is trying to scam you using my name and my avatar on social media, asking for money.”

Even Facebook’s top executives, including Mark Zuckerberg, have struggled with impersonators.

To get a sense of the scale of the problem, The New York Times commissioned an analysis to tally the number of impersonators across social media for the 10 most followed people on Instagram, including Beyonce and Taylor Swift. The analysis, conducted by Social Impostor, a firm that protects celebrities’ names online, found nearly 9,000 accounts across Facebook, Instagram and Twitter pretending to be those 10 people.

Brazilian soccer player Neymar was the subject of the most fake accounts, 1,676. Pop star Selena Gomez was second, with 1,389, according to the analysis, which was completed in April and did not count explicit parody or fan pages. BeyoncE had 714 impersonators; Swift had 233, the least among the group.

Twitter, Instagram and Facebook have compounded the problem with lax enforcement of their own policies prohibiting impersonators. Some people who report such accounts said the sites had gotten better at removing them, but others said the companies did not police them adequately. Most people agreed that once the sites erased the accounts, they did little to keep those behind them from creating new ones.

Facebook and its Instagram unit said they were cracking down on fake accounts. The social network said it had recently added software that automatically detected impostors and frauds, which it used to remove more than 1 million accounts since March.

Yet in April, tucked away in the fine print of an earnings document, Facebook increased its estimate of fake accounts on the site by 20 million — to as many as 80 million accounts, or 4 per cent of the total number of accounts. The company said the site’s sheer size made it difficult to measure the problem.

A DISHEARTENING THING

For many celebrities, the flood of fake social media accounts can cause real-life headaches.

Trace Adkins, the country music singer, said he had encountered people at nearly every show who claimed that in online messages, he had promised them free tickets and a backstage tour.

Women regularly tell Adkins he had proposed to them online. “I mean it’s off-the-charts crazy, man,” he said. “But people believe this stuff, and we have to deal with it.”

When I messaged an Instagram account pretending to belong to Adkins, the impostor directed me to a profile impersonating the singer’s daughter.

The account, which had posted numerous photos of the college-age Adkins, said she had started a charity and sent me a photo of a man in a hospital bed.

Whoever was behind the fake account then asked for a donation “to pay a dying man’s hospital bill.” The sum? $14,700. When I demurred, the impostor wrote snippily, “Are you willing to help us with money or what?”

Moore said the fake accounts had weighed on him. He recently got a message from a man who said his wife was leaving him for Moore after she had started a relationship with the singer online. When he clicked on the woman’s profile, he found a 60-year-old mother of five.

“How can it not bother me?” Moore said. “I have people like, ‘You’re the biggest scumbag ever. You were doing this, messaging my mom or whatever.’ It’s a disheartening thing, when you’re viewed a certain way by people that has nothing to do with your character in real life.”

HOW EASY IS IT TO FAKE IT?

How easy is it to impersonate someone online? To find out, I created my own impostors.

For those at home: I do not recommend doing this. Making fake social media accounts, even of yourself, is forbidden by the companies’ terms of service. After I made the accounts, I also informed the companies so that the profiles could be removed.

Making the duplicate accounts turned out to be a breeze. I recently created eight Facebook accounts in one hour that purported to be me, using my exact name and job title and a photo pulled from my verified profile. All that was required was a different email address for each account. (Email addresses are free and plentiful on the internet.)

On the fifth account, Facebook blocked me from using my name. I thought the jig was up. Then I added a middle initial, and the profile was approved. Later, I deleted the middle initial. After I had created eight fake accounts, Facebook began requiring a phone number. So I waited a few days and then created three more.

The fake accounts were live for five days before I reported them via Facebook’s site. The company removed them all within minutes.

I used many of the same email addresses to construct Instagram impostors of myself. Instagram made it trickier, sometimes requiring a phone number, which I never offered, or blocking me outright. But by using several different devices, like my wife’s phone, I eventually created 10 profiles with my name and bio and a photo pulled from my verified account.

I then reported the 10 accounts to Instagram. The photo-sharing site removed five after a day. The other five were still active more than four days later.

Twitter was better. After I successfully created one impostor, the company blocked me from using my actual profile photo on a second phoney account. The company quickly removed the impersonator when I reported it.

To conclude my experiment, I reported more than 30 celebrity impostor accounts to the companies — including all the examples cited in this article — to see what would happen.

I received responses to only six of those reports, all from Instagram. They included two Moore impersonators and a phoney Winfrey, with 727 followers, which had posted images of sick and poor children and had asked for donations. Instagram said the accounts did not violate its policies. There was no option to appeal.

Instagram removed one account that I flagged, which impersonated Swift, although the company did not notify me.

“We take the reports really seriously,” said Pete Voss, a Facebook and Instagram spokesman, adding that the company would remove the other accounts I had reported. “We’re not going to get it 100 per cent right every time obviously.”

Ian Plunkett, a Twitter spokesman, said the company had “strict policies and enforcement procedures” regarding impersonation, and he directed me to the company’s rules.

Dickens, the Facebook product manager, said that the company was trying to stamp out every pretender but that the task was complicated by the social network’s size; the nuance of separating imitators from fan pages; and the sophistication of some of the impostors.

“It’s the arms race,” he said.