Defying geographic odds, artists and writers have long had a habit of disappearing down under, attracted by Tasmania’s wild natural beauty and English-like countryside. Some 240km from the south-east tip of mainland Australia, the island was settled as a British prison colony in 1803. Very soon, creative types started rocking up on its shores.

Landscape painter John Glover was one of many painters who, in the 1830s, did “a disappearing act” to Tasmania, as novelist Nicholas Shakespeare put it after several years living there himself.

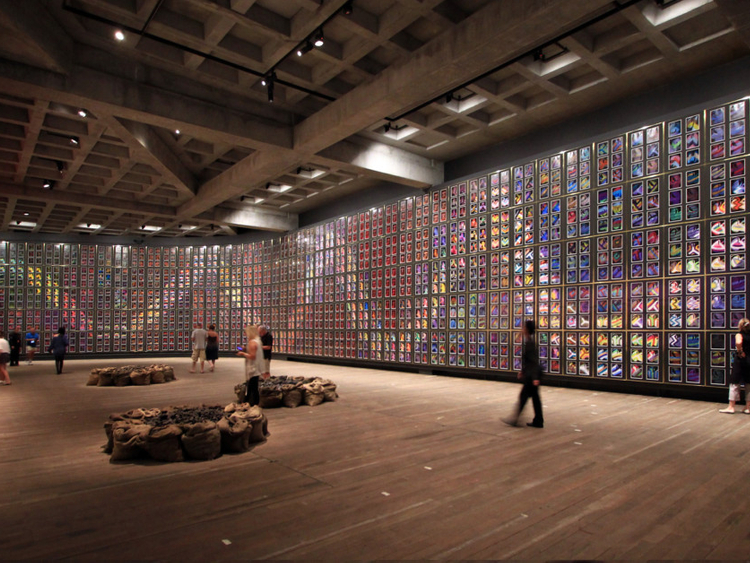

The island’s beauty is a creative magnet as much as an inspiration. The greatest symbol of that today is Mona — Tasmania’s cheekily named answer to New York’s Museum of Modern Art (Moma), the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona).

Since opening in 2011, some 1.5 million people from all over the world have filed in through its doors.

Drawing visitors in droves

Art has brought many more visitors to the island state than leg chains ever did. Within less than two years, Mona established itself as the state’s leading tourism attraction ahead of its convict heritage and natural attractions. On top of that it’s become a powerful part of Tasmanian urban culture — a morale booster for the often beleaguered state economy.

Founded by local millionaire art collector David Walsh — passed off in the press as an enigmatic, gambling genius and intensely outré yet generous arts patron (entry to his museum is free for Tasmanians) — his anti-museum in August beat Moma and London’s Tate Modern to be named the world’s best modern art gallery by Lonely Planet. That for an establishment whose prized contents include an Egyptian sarcophagus, rotting cow carcasses, a neon waterfall cascading Google search tags and a library of blank books.

To the accusation the collection is more about showmanship than art, Walsh replies with typical irreverence. “My rule was we’ll never spend any money on advertising; we’ll do stuff that attracts attention.”

The experience of getting there is part of the novelty. Most visitors climb aboard a ferry at the Hobart docks and set sail for Mona 20 minutes upstream.

Walsh pushed the art and architectural stakes higher by plonking the stark concrete-and-steel monolith — designed to echo classical Greek temples — in the suburbs in which he grew up. Even its location is challenging, Walsh admits. “If this was in Melbourne you’d probably pop in every now and again. Here people have made the effort to come — the average visitor time is three hours and 20 minutes.”

Intriguing installations

The contents are as perplexing and confronting as Walsh himself. Among iconic Australian art such as the 1970 mural Snake by Sidney Nolan, the 200 oeuvres include a bulimic Porsche (the fat car), mummies and a poo-producing machine.

“Its most loathed exhibit is also one of its most popular,” wrote Tasmania’s renowned Booker Prize-winning author Richard Flanagan in The New Yorker, referring to Walsh as a Tasmanian devil. “Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca Professional is a large, reeking machine that replicates the human digestive system, turning food into faeces, which it excretes daily at 2pm.”

Walsh is still busily pulling in the best art and architectural talent worldwide to help him achieve his undefined and rambling dream for the museum. “The response to Mona has been overwhelming and I didn’t expect it to be,” he says.

Plans are adrift for gallery extensions, a hotel — Hotel Mona or Homo — riverside boardwalks, a library and Venice-style ferries (read: vaporetti). “In fact we now have plans for more than 20 hotels for the site.”

His most controversial plan is for Mona’s gambling appendage, the onsite casino.

Mona says a lot about Tasmania’s transformation from a conservative bastion to a creative island hub. Long known as the Apple Isle and more recently the holiday isle, it is fast gaining renown for its arty side. And the museum and its festivals have helped put Tasmania firmly on the cultural map.

Carnival of culture

The January Mofo — a five-day festival of art, music and food — caps off an already billowing array of well-established artistic events on the island.

The carnival of culture is curated by Violent Femmes bassist Brian Ritchie — another celebrity wooed by Tasmania’s end-of-the-world beauty — along with performers of the likes of John Cale, Elvis Costello, Nick Cave and Philip Glass.

The biennial Ten Days on the Island in March, which brings together performing artists from islands around the world, celebrates the cultural uniqueness of far-off islands and their huge powers of attraction.

For writer and intellectual Pete Hay, the “shock-art museum” — as London’s Daily Telegraph described Mona — isn’t solely responsible for that fame. He says Richard Flanagan did wonders to unleash Tasmania’s creative spirit to the world, starting with his first novel in the early 1990s and culminating in 2014’s Burma railway-inspired The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

“The publication of Death of a River Guide is the most important cultural event in Tasmanian history, only matched perhaps, by the coming of Mona,” Hay explains.

“In its wake, a cultural confidence burgeoned — in all the arts there was a flowering.”

Flanagan, he says, helped lift the negative shadow from Tasmanian history, which had made it an unpalatable subject for earlier writers. “He made it legitimate to stay put, to take Tasmania for one’s creative canvas.”

While Mona has brought visitors to Tasmania, Flanagan “took Tasmania to the world”.

Put the two together — with all the other creative forces in the state — and Tasmania is becoming a true artistic tour de force. And big-name artists and writers are increasingly heading to this Gondwanaland straggler to lose themselves in the island’s creative solitude.