A Danish biotechnology company is trying to fight climate change — one laundry load at a time. Its secret weapon: mushrooms like those in a dormant forest outside Copenhagen.

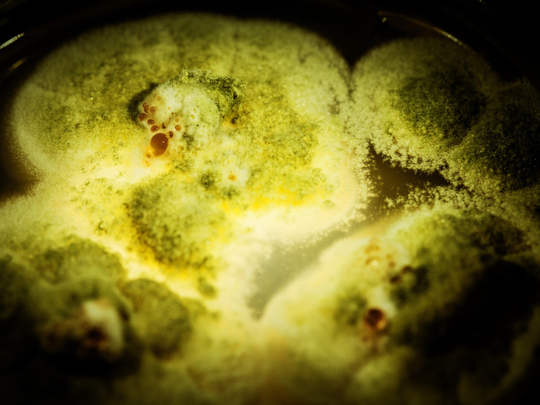

In the quest for a more environmentally friendly detergent, two scientists at the company, Novozymes, regularly trudge through the mud, hunting for oyster mushrooms that protrude from a fallen beech or bracken fungi that feast on tough plant fibres. They are studying the enzymes in mushrooms that speed up chemical reactions or natural processes such as decay.

“There is a lot going on here, if you know what to look for,” said Mikako Sasa, one of the Novozymes scientists.

Their work is helping the company develop enzymes for laundry and dishwasher detergents that would require less water, or that would work just as effectively at lower temperatures. The energy savings could be significant. Washing machines, for instance, account for more than 6 per cent of household electricity use in the European Union.

Enlisting enzymes to battle dirt is not a new strategy. Over thousands of years, mushrooms and their fungi cousins have evolved into masters at nourishing themselves on dying trees, fallen branches and other materials. They break down these difficult materials by secreting enzymes into their hosts. Even before anyone knew what enzymes were, they were used in brewing and cheese-making, among other activities.

In 1833, French scientists isolated an enzyme for the first time. Known as diastase, it broke starch down into sugars. By the early 20th century, a German chemist had commercialised the technology, selling a detergent that included enzymes extracted from the guts of cows.

Novozymes and its rivals have developed a catalogue of enzymes over the years, supplying them to consumer goods giants such as Unilever and Procter & Gamble.

At the company’s low-slung 1960s-style campus, scientists in white lab coats and armed with miniature washing machines test new enzyme combinations on dollsize cutouts of clothing. To test a product’s stain-fighting prowess, they import stain samples from around the world, such as greasy, blackened collars and yellow armpit stains.

Modern detergents contain as many as eight different enzymes. In 2016, Novozymes generated about $2.2 billion in revenue and provided enzymes for detergents including Tide, Ariel and Seventh Generation.

The quantity of enzymes required in a detergent is relatively small compared with chemical alternatives, an appealing quality for customers looking for more natural ingredients. A tenth of a teaspoon of enzymes in a typical laundry load cuts by half the amount of soap from petrochemicals or palm oil in a detergent.

Enzymes are also well suited to helping cut energy consumption. They are often found in relatively cool environments, such as forests and oceans. As a result of that low natural temperature, they do not require the heat and pressure typically used in washing machines and other laundry processes.

So consumers can reduce the temperatures on their washing machines while ensuring their shirts stay lily white. Lowering the temperature on a washing machine cycle to cold water from 40˚Celsius (104˚Fahrenheit) reduces energy consumption by at least half, according to the International Association for Soaps, Detergents and Maintenance Products, an industry group.

“We think there are a lot of systems and processes in nature that are extremely resource efficient,” said Gerard Bos, director of the global business and biodiversity programme at the International Union for Conservation of Nature in Switzerland. “In nature, there is basically no waste. Every material gets reused.”

In 2009, Novozymes scientists teamed up with Procter & Gamble to develop an enzyme that could be used in liquid detergents for cold-water washes. Researchers started with an enzyme from soil bacteria in Turkey, and modified it through genetic engineering to make it more closely resemble a substance found in cool seawater. When they found the right formula, they called the enzyme Everest, a reference to the scale of the task accomplished.

“We knew this was something that consumers would want,” said Phil Souter, associate director of Procter & Gamble’s research and development unit in Newcastle, England. “I think this is a very tangible and practical way people can make a difference in their everyday lives.”

Next, they found a way to mass produce the enzyme. Novozymes implanted the newly-developed product’s DNA into a batch of microbial hosts used to cultivate large volumes of enzymes quickly and at low cost. The enzymes were then “brewed” in large, closely monitored tanks before being sold.

The result: a crucial ingredient in detergents like Tide Cold Water.

“This is biotechnology on a very large scale,” said Jes Bo Tobiassen, the manager of a Novozymes manufacturing facility in Kalundborg, a small coastal city in Denmark.

As it researches new enzymes, Novozymes is trying to reach consumers in fast-growing economies, like China.

In much of the developed world, laundry habits are relatively entrenched. Europeans tend to use front-loading washers, which are far more efficient in energy and water use than the top-loaders favoured in the United States.

But in China, members of the growing middle class like Shen Hang are upgrading washing machines and turning to more expensive, higher-quality detergents. While Chinese consumers are among the world’s most frequent and fastidious washers of clothes, according to Novozymes researchers, they are not as set in their ways.

Shen recently bought an efficient front-loading washer-dryer. But he has struggled to find a detergent that can get his sweat-stained shirt collars clean.

“I’m kind of sick of that,” he said of manufacturers’ exaggerated claims.

He uses two types of bleach, one for white clothes and one for coloured. If they do not work, he manually rubs the stains with his hands. He repeats that cycle three times a week.

Sensing an opportunity, Novozymes’ commercial teams have pushed the company’s scientists to create enzymes that would perform better in the bleach-filled washes favoured in China.

The company has made progress. A newly-developed enzyme named Progress Uno is being added to liquid detergents manufactured by Liby, a Chinese company.

At this point, Chinese consumers mostly wash at low temperatures. But Peder Holk Nielsen, the chief executive of Novozymes, worries that could change as wealth in China grows. Consumers did the same in the West in the decades after the Second World War, Nielsen said.

But if, thanks to enzyme development, that transition can be avoided, that would be “a phenomenal sustainability story,” he said. “It is going to save so much water, and so much energy.”

–New York Times News Service