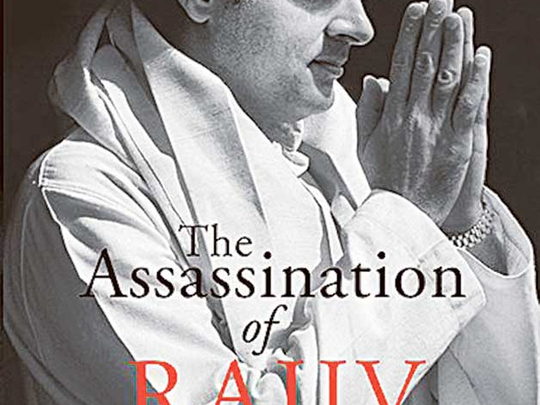

The Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi

By Neena Gopal, Penguin/Viking, 240 pages, $30

At 10.21 on the night of May 21, 1991, in Sriperumbudur, a town 40 kilometres south of Chennai in the large Indian state of Tamil Nadu, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated by a suicide bomber who would turn out to be a member of the Tamil Tigers who were fighting for independence for the Tamil area in the neighbouring country of Sri Lanka. Gandhi was in the middle of a general election seeking to regain power for the Congress Party, of which he was leader.

Gulf News reporter Neena Gopal had been following the campaign trail for some weeks, reporting on this vital election campaign for the newspaper back in Dubai. The previous day Gopal had been in Chennai, seeking a private chat with Tamil leader Jayalalitha at her home in Poes Garden, when she got a call from Mani Shanker Aiyer, the former diplomat and Gandhi’s campaign manager for that election, telling her that a long-promised exclusive interview with Gandhi would be possible the next day.

Gopal rushed south to join the campaign and conducted the interview with Gandhi in his car as he was driven to the election rally. “In my mind’s eye I can still see Rajiv Gandhi’s gentle smile that showed not the slightest irritation at the less than conducive arrangements at the rally venue,” she writes in her new book “The Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi”. As she continued with what was the last interview that Gandhi ever gave, the car moved through the surging crowds to the rally.

As Gandhi got out, Gopal said, “I have one last question. I’ll wait for you here.” He walked forward unhesitatingly into the crowd to get to the podium, and “there was a deafening sound as the bomb spluttered to life and exploded in a blinding flash. Everything changed.”

“The Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi” starts with the terrible day the assassination, its immediate aftermath and the following weeks as the perpetrators were tracked down. But the bulk of the book tells the wider story of the Sri Lankan Tamils’ relationships with India and Sri Lanka, based on Gopal’s excellent reporting, which takes her to meet a wide variety of officers from the Indian army, navy and intelligence service, the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), sources in the Indian government and many Sri Lankan and Tamil officials.

She tracks with detail the intimate relations between the Indian security and military services with the Tamil separatists that went back decades before Gandhi’s killing. The book then takes the story forward through the tortured events of the following decades up to the final defeat of the Tamil Tigers by Sri Lankan forces under President Mahinda Rajapaksa. It ends with one of the most interesting chapters which looks at the totally transformed circumstances of today, ending with Gopal going back to visit to a vibrant and confident Jaffna in northern Sri Lanka where she met many former Tiger combatants building their new lives in a peaceful economy.

The large part of the value in “The Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi” is in the reporting of detailed conversations that bring to life the complex politics of the Indo-Sri Lankan relationship of the 1970s and 1980s. This sad story started back in the 1800s when hundreds of thousands of Tamils moved to Ceylon under the British government and settled into new lives working on the tea estates and elsewhere. But almost immediately after Ceylon gained independence in 1948, the new government passed the controversial Ceylon Citizenship Act that made it almost impossible for the Tamil minority to become citizens. This meant that more than 700,000 Tamils became stateless, and more than 300,000 Tamils were deported to India. This discrimination created a wave of resentment among Tamils in both Sri Lank and India, which was coupled with the growing mistrust between Sri Lanka and India, as Sri Lankan Prime Minister J.R. Jayawardene won a landslide victory in 1977 and shifted his country to become more pro-Western.

This meant that Sri Lanka became the first South Asian state to adopt liberal open-economy policies, and while Jayawardene had enjoyed a close relationship with the founding Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, which enabled them to bridge the gaps between them, this did not carry over to Nehru’s successor and daughter, Indira Gandhi. She resented the political direction that Jayawardene, which was part of her taking the decision to support the insurgent groups operating in Sri Lanka as she also listened to the very important Tamil community of India that was hosting large groups of Tamil refugees.

It was in this context that Indian forces started working with Tamil exiles, and by mid-1983 Indira Gandhi instructed India’s intelligence service, RAW, to start funding and training several Tamil insurgent groups, which eventually led to Indian forces actively supporting insurgent groups operating in northern Sri Lanka. Among many such groups, one of the most determined was the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, LTTE, headed by Velupillai Prabhakaran, who developed his own military and intelligence contacts with the Indian forces, as well as sought more conventional support from leading Tamil politicians such as M.G. Ramachandran or M. Karunanidhi, both of whom succeeded each other as chief ministers of Tamil Nadu.

When Rajiv Gandhi became India’s prime minister in 1984 after his mother was assassinated, he continued to back the Tamil groups in Sri Lanka, most famously using Indian forces to break the Sri Lankan blockade of Jaffna in 1986. But in 1987 he signed the Indo-Sri Lankan Accord and sent the Indian Peace Keeping Force to try and both protect the Tamils and enforce the ceasefire. This failed, so in 1989 he withdrew the IPKF. This aroused the fury of the LTTE which felt deeply betrayed by its former allies in the Indian government, which eventually triggered his assassination.

Gopal successfully guides the reader through the complex and quickly changing relationships between the Indian forces and the Tigers before and after the assassination, charting how the earlier friendly support gave way to suspicion and then to outright opposition. Gopal gets the story from all sides, often matching conversations with a former Indian intelligence officer with a counter view from the Sri Lankan side, and many interpolations from Tamils. She includes comments from both those who were active in the Tigers’ military wing and some who were more political or just Tiger sympathisers, as well as non-Tiger Tamil politicians who hated what the Tigers were doing, but had to find a way to live and try to build a future for their people in the heated atmosphere of those times.

Gopal ends her book by dismissing the naysayers and doomsday projections, pointing out that the Sri Lankan Tamils have gone from bust to boom. She agrees that the situation in the Tamil areas of Sri Lanka is still a work in progress but makes clear that she thinks that there is now nothing to hold them back but themselves. “The Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi” brings the clarity of good reporting and story-telling to describe how that extraordinary journey has been made.

–Neena Gopal is now the Resident Editor of the Deccan Chronicle in Bengaluru.