By Tom Rachman, Riverrun, 336 pages, ₤16.99

Bear Bavinsky is, apparently, a genius. He paints women like one possessed, paints them on big canvases, homing in on one almost dehumanising detail, so that his sought-after “Life-Stills” remain all about him, never about the identity or character of his long-suffering muses, who appear in them simply as a knee or a shoulder or an eyebrow. Most of his paintings fail to live up to his Olympian ideals and he burns most of them in a dustbin on the spot. With characteristic high-minded arrogance, he dislikes selling his work to mere individuals, preferring that it pass immediately into the hands of the world’s great galleries.

Bavinsky shrewdly curates his own professional mystique. His private life, naturally, is a battlefield. No one woman is ever enough for his restless need for stimulus and adoration. A genial narcissist, he has numerous liaisons and marriages, numerous changes of address, numerous children. The man is an insecure, macho man in the Hemingway mould but most can overlook that, because his work is a beautiful wonder that will outlive him.

The world of art, like that of fashion, is a soft target, easily satirised not least because its big beasts can seem to send themselves up before the writer even gets to them. Bear’s story could have made a blackly funny fable told by William Boyd or Will Self, say. The genius of Tom Rachman’s fourth novel, however, is to have nudged the camera tripod so that, while Bear continues to make most of the noise and believe the story is all about him, the narrative focuses instead on his utterly overlooked eldest son.

The constantly marginalised Pinch is first encountered aged five, living with his bipolar potter mother, Natalie, in Bear’s squalid studio in Rome in the mid-Fifties. He believes in his father’s genius as men once believed in God, and is cursed by his inability ever to amount to anything that might win the man’s genuine admiration. Bear casually bestows a few art lessons on the growing boy before abandoning him and his mother for another woman and another country, but those lessons take root to the point where his mother is convinced of, and encourages, his gift.

Growing into a predictably awkward adolescent, blessed with stylishly fluent Italian, Pinch pursues his artistic course only to have his father deny his talent with a single, brutally casual comment. Unwavering in his faith, he studies instead to become an art critic, the better to celebrate his father’s genius, only to end by wasting his life as the common room oddball of a soulless London language school.

He experiences varying degrees of love and emotional fulfilment with three wildly contrasted women and yet the thing that continues to consume him, albeit in secret, is painting. And even though their paths cross so rarely that he hoards every detail of every meeting, his father’s destiny and reputation and his own come to be deliciously, subversively entwined as Rachman’s novel slaloms through its utterly unpredictable course.

The Italian Teacher is often wickedly funny — Rachman has an eye for life’s cruelty worthy of Waugh — but it is also deeply touching in its tender portrayals of life’s victims, such as poor Natalie, who pursues her clumsy art without encouragement or reward: “At the counter, she knocks over their pot of hot water, then insists on cleaning the puddle, grabbing handfuls of the restaurant’s paper towels despite the waitstaff telling her it’s quite all right: ‘Really. Just leave it. Please.’ Natalie won’t. The queue lengthens, everyone glowering at this kook on her hands and knees, wiping the floor.”

Although the art world and its monsters are evoked in loving and less than loving detail, from Fifties Rome to Seventies New York to the Hirstian excesses of the early 21st-century gallery scene, this is really a novel about authenticity. Most obviously, it questions the authenticity of Bear Bavinsky’s essentially lonely genius but, more slyly, it explores authenticity of fatherhood, of intimacy, of self-belief. Pinch’s funny-sad story begins as a quest for recognition — as a son, as an artist and then as a writer — but then, almost without his noticing, becomes the story of someone disappearing and going to insane lengths to leave no trace.

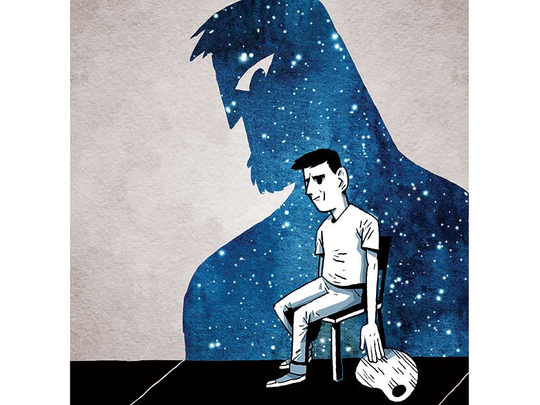

Inevitably, as it covers all but five years in a man’s life, this is also a novel about mortality and the body’s steady slackening and betrayal. Pinch is as pitiful a specimen as his lifelong nickname implies, and does himself few favours, so that the reader longs to rescue him from himself and his terrible dress sense, but one of Rachman’s great achievements here is to convey the sense of the passionate, ever-hopeful soul trapped behind the kind of appearance over which people’s glances skate.

Art — the pursuit of it, the admiration of it, the coveting of it and the fighting over its legacy — comes, here, to seem to be about mortality and the deeply human need to make our mark. I confess this was the first of Rachman’s novels I’d read but I was so swept away by it that I raced out to buy the other three.

–The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2018

Patrick Gale’s latest novel, Take Nothing With You, is out this year