With the death of Richard Wilbur in October, Philip Roth became the longest-serving member in the literature department of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, that august Hall of Fame on Audubon Terrace in northern Manhattan, which is to the arts what Cooperstown is to baseball. He’s been a member so long he can recall when the academy included now all-but-forgotten figures like Malcolm Cowley and Glenway Wescott — white-haired luminaries from another era. Just recently Roth joined William Faulkner, Henry James and Jack London as one of very few Americans to be included in the French Pleiades editions (the model for our own Library of America), and the Italian publisher Mondadori is also bringing out his work in its Meridiani series of classic authors.

All this late-life eminence — which also includes the Spanish Prince of Asturias Award in 2012 and being named a commander in the Legion d’Honneur of France in 2013 — seems both to gratify and to amuse him. “Just look at this,” he said to me in December, holding up the ornately bound Mondadori volume, as thick as a Bible and comprising titles like “Lamento di Portnoy” and “Zuckerman Scatenato.” “Who reads books like this?”

In 2012, as he approached 80, Roth famously announced that he had retired from writing. (He actually stopped two years earlier.) In the years since, he has spent a certain amount of time setting the record straight. He wrote a lengthy and impassioned letter to Wikipedia, for example, challenging the online encyclopedia’s preposterous contention that he was not a credible witness to his own life. (Eventually, Wikipedia backed down and redid the Roth entry in its entirety.)

Roth is also in regular touch with Blake Bailey, whom he appointed as his official biographer and who has already amassed 1,900 pages of notes for a book expected to be half that length. And just recently, he supervised the publication of Why Write?, the 10th and last volume in the Library of America edition of his work. A sort of final sweeping up, a polishing of the legacy, it includes a selection of literary essays from the 1960s and 1970s; the full text of Shop Talk, his 2001 collection of conversations and interviews with other writers, many of them European; and a section of valedictory essays and addresses, several published in the US for the first time. Not accidentally, the book ends with the three-word sentence “Here I am” — between hard covers, that is.

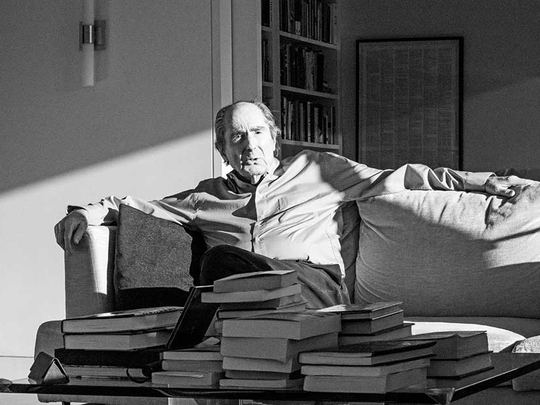

But mostly now Roth leads the quiet life of an Upper West Side retiree. (His house in Connecticut, where he used to seclude himself for extended bouts of writing, he now uses only in the summer.) He sees friends, goes to concerts, checks his email, watches old movies on FilmStruck. Not long ago he had a visit from David Simon, the creator of The Wire, who is making a six-part mini-series of The Plot Against America, and afterward he said he was sure his novel was in good hands. Roth’s health is good, though he has had several surgeries for a recurring back problem, and he seems cheerful and contented. He’s thoughtful but still, when he wants to be, very funny.

I have interviewed Roth on several occasions over the years, and in December I asked if we could talk again. Like a lot of his readers, I wondered what the author of American Pastoral, I Married a Communist and The Plot Against America made of this strange period we are living in now. And I was curious about how he spent his time. Sudoku? Daytime TV? He agreed to be interviewed but only if it could be done via email. He needed to take some time, he said, and think about what he wanted to say.

Excerpts:

In a few months you’ll turn 85. Do you feel like an elder? What has growing old been like?

Yes, in just a matter of months I’ll depart old age to enter deep old age — easing ever deeper daily into the redoubtable Valley of the Shadow. Right now it is astonishing to find myself still here at the end of each day. Getting into bed at night I smile and think, “I lived another day.” And then it’s astonishing again to awaken eight hours later and to see that it is morning of the next day and that I continue to be here. “I survived another night,” which thought causes me to smile once more. I go to sleep smiling and I wake up smiling. I’m very pleased that I’m still alive.

Moreover, when this happens, as it has, week after week and month after month since I began drawing Social Security, it produces the illusion that this thing is just never going to end, though of course I know that it can stop on a dime. It’s something like playing a game, day in and day out, a high-stakes game that for now, even against the odds, I just keep winning. We will see how long my luck holds out.

Now that you’ve retired as a novelist, do you ever miss writing, or think about un-retiring?

No, I don’t. That’s because the conditions that prompted me to stop writing fiction seven years ago haven’t changed. As I say in Why Write?, by 2010 I had “a strong suspicion that I’d done my best work and anything more would be inferior. I was by this time no longer in possession of the mental vitality or the verbal energy or the physical fitness needed to mount and sustain a large creative attack of any duration on a complex structure as demanding as a novel ... Every talent has its terms — its nature, its scope, its force; also its term, a tenure, a life span ... Not everyone can be fruitful forever.”

Looking back, how do you recall your 50-plus years as a writer?

Exhilaration and groaning. Frustration and freedom. Inspiration and uncertainty. Abundance and emptiness. Blazing forth and muddling through. The day-by-day repertoire of oscillating dualities that any talent withstands — and tremendous solitude, too. And the silence: 50 years in a room silent as the bottom of a pool, eking out, when all went well, my minimum daily allowance of usable prose.

In Why Write? you reprint your famous essay Writing American Fiction, which argues that American reality is so crazy that it almost outstrips the writer’s imagination. It was 1960 when you said that. What about now? Did you ever foresee an America like the one we live in today?

No one I know of has foreseen an America like the one we live in today. No one (except perhaps the acidic H.L. Mencken, who famously described American democracy as “the worship of jackals by jackasses”) could have imagined that the 21st-century catastrophe to befall the USA, the most debasing of disasters, would appear not, say, in the terrifying guise of an Orwellian Big Brother but in the ominously ridiculous commedia dell’arte figure of the boastful buffoon. How naive I was in 1960 to think that I was an American living in preposterous times! How quaint! But then what could I know in 1960 of 1963 or 1968 or 1974 or 2001 or 2016?

Your 2004 novel, The Plot Against America, seems eerily prescient today. When that novel came out, some people saw it as a commentary on the Bush administration, but there were nowhere near as many parallels then as there seem to be now.

However prescient The Plot Against America might seem to you, there is surely one enormous difference between the political circumstances I invent there for the US in 1940 and the political calamity that dismays us so today. It’s the difference in stature between a President Lindbergh and a President Trump. Charles Lindbergh, in life as in my novel, may have been a genuine racist and an anti-Semite and a white supremacist sympathetic to Fascism, but he was also — because of the extraordinary feat of his solo trans-Atlantic flight at the age of 25 — an authentic American hero 13 years before I have him winning the presidency.

Lindbergh, historically, was the courageous young pilot who in 1927, for the first time, flew nonstop across the Atlantic, from Long Island to Paris. He did it in 33.5 hours in a single-seat, single-engine monoplane, thus making him a kind of 20th-century Leif Ericson, an aeronautical Magellan, one of the earliest beacons of the age of aviation. Trump, by comparison, is a massive fraud, the evil sum of his deficiencies, devoid of everything but the hollow ideology of a megalomaniac.

One of your recurrent themes has been male sexual desire — thwarted desire, as often as not — and its many manifestations. What do you make of the moment we seem to be in now, with so many women coming forth and accusing so many highly visible men of sexual harassment and abuse?

I am, as you indicate, no stranger as a novelist to the erotic furies. Men enveloped by sexual temptation is one of the aspects of men’s lives that I’ve written about in some of my books. Men responsive to the insistent call of sexual pleasure, beset by shameful desires and the undauntedness of obsessive lusts, beguiled even by the lure of the taboo — over the decades, I have imagined a small coterie of unsettled men possessed by just such inflammatory forces they must negotiate and contend with. I’ve tried to be uncompromising in depicting these men each as he is, each as he behaves, aroused, stimulated, hungry in the grip of carnal fervour and facing the array of psychological and ethical quandaries the exigencies of desire present.

I haven’t shunned the hard facts in these fictions of why and how and when tumescent men do what they do, even when these have not been in harmony with the portrayal that a masculine public-relations campaign — if there were such a thing — might prefer. I’ve stepped not just inside the male head but into the reality of those urges whose obstinate pressure by its persistence can menace one’s rationality, urges sometimes so intense they may even be experienced as a form of lunacy. Consequently, none of the more extreme conduct I have been reading about in the newspapers lately has astonished me.

Before you were retired, you were famous for putting in long, long days. Now that you’ve stopped writing, what do you do with all that free time?

I read — strangely or not so strangely, very little fiction. I spent my whole working life reading fiction, teaching fiction, studying fiction and writing fiction. I thought of little else until about seven years ago. Since then I’ve spent a good part of each day reading history, mainly American history but also modern European history. Reading has taken the place of writing, and constitutes the major part, the stimulus, of my thinking life.

What have you been reading lately?

I seem to have veered off course lately and read a heterogeneous collection of books. I’ve read three books by Ta-Nehisi Coates, the most telling from a literary point of view, The Beautiful Struggle, his memoir of the boyhood challenge from his father. From reading Coates I learned about Nell Irvin Painter’s provocatively titled compendium The History of White People. Painter sent me back to American history, to Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom, a big scholarly history of what Morgan calls “the marriage of slavery and freedom” as it existed in early Virginia.

Reading Morgan led me circuitously to reading the essays of Teju Cole, though not before my making a major swerve by reading Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve, about the circumstances of the 15th-century discovery of the manuscript of Lucretius’ subversive On the Nature of Things. This led to my tackling some of Lucretius’ long poem, written sometime in the first century BCE, in a prose translation by A.E. Stallings. From there I went on to read Greenblatt’s book about “how Shakespeare became Shakespeare,” Will in the World. How in the midst of all this I came to read and enjoy Bruce Springsteen’s autobiography, Born to Run, I can’t explain other than to say that part of the pleasure of now having so much time at my disposal to read whatever comes my way invites unpremeditated surprises.

Pre-publication copies of books arrive regularly in the mail, and that’s how I discovered Steven Zipperstein’s Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History. Zipperstein pinpoints the moment at the start of the 20th century when the Jewish predicament in Europe turned deadly in a way that foretold the end of everything. Pogrom led me to find a recent book of interpretive history, Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century, which argues that “the Modern Age is the Jewish Age, and the 20th century, in particular, is the Jewish Century.” I read Isaiah Berlin’s Personal Impressions, his essay-portraits of the cast of influential 20th-century figures he’d known or observed.

There is a cameo of Virginia Woolf in all her terrifying genius and there are especially gripping pages about the initial evening meeting in badly bombarded Leningrad in 1945 with the magnificent Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, when she was in her 50s, isolated, lonely, despised and persecuted by the Soviet regime. Berlin writes, “Leningrad after the war was for her nothing but a vast cemetery, the graveyard of her friends. ... The account of the unrelieved tragedy of her life went far beyond anything which anyone had ever described to me in spoken words.” They spoke until 3 or 4 in the morning. The scene is as moving as anything in Tolstoy.

Just in the past week, I read books by two friends, Edna O’Brien’s wise little biography of James Joyce and an engagingly eccentric autobiography, Confessions of an Old Jewish Painter, by one of my dearest dead friends, the great American artist R.B. Kitaj. I have many dear dead friends. A number were novelists. I miss finding their new books in the mail.

–New York Times News Service

Charles McGrath is the editor of a Library of America collection of John O’Hara stories.