A writhing dragon rises from Mount Fuji in a pall of smoke and swirls to the heavens. The mountain is covered in snow, the landscape is desolate in shades of grey. There are no people.

An atmosphere of melancholy, perhaps of ending, pervades the painting by the artist who called himself Old Man Crazy to Paint - better known as the Japanese master Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849).

In fact, Dragon Rising Above Mount Fuji was one of the artists last works and it has all the symbolism that characterises his spiritualism, his constant commitment to Buddhism and his yearning for immortality.

The latest exhibition at London’s British Museum, Hokusai: beyond the Great Wave (Until August 13) concentrates on the later years of the artist and is a rare insight into his transcendent skills. Many of the works have never been seen in the UK and so sensitive to light are the vivid colours that many can only be displayed for a limited time. The exhibition, which is supported by Mitsubishi Corporation, will be closed from July 3-6 to replace about 110 works.

What they all show is Hokusai’s constant striving for perfection which grew more intense the older he became.

As he wrote: “At seventy-three, I began to grasp the structures of birds and beasts, insects and fish, and of the way plants grow. If I go on trying, I will surely understand them still better by the time I am eighty-six, so that by ninety I will have penetrated to their essential nature. At one hundred, I may well have a positively divine understanding of them, while at one hundred and thirty, forty, or more I will have reached the stage where every dot and every stroke I paint will be alive. May Heaven, that grants long life, give me the chance to prove that this is no lie.”

Heaven did not grant him the length of life he prayed for but Dragon Rising above Mount Fuji was completed in the first month of his ninetieth year, a time of great symbolism for the artist who was born in a dragon year and painted the work on a dragon day.

His work is imbued with his belief in the Nichiren sect of Buddhism who believe in the North Star as a personification of a deity. Hokusai whose name translates as North Studio, drew on the power of the North Star in the hope of extending his time on earth.

Much of his work features symbols of life such as waterfalls and mountains and reflect his animistic belief that every natural thing in the universe - trees, flowers and birds - has a soul.

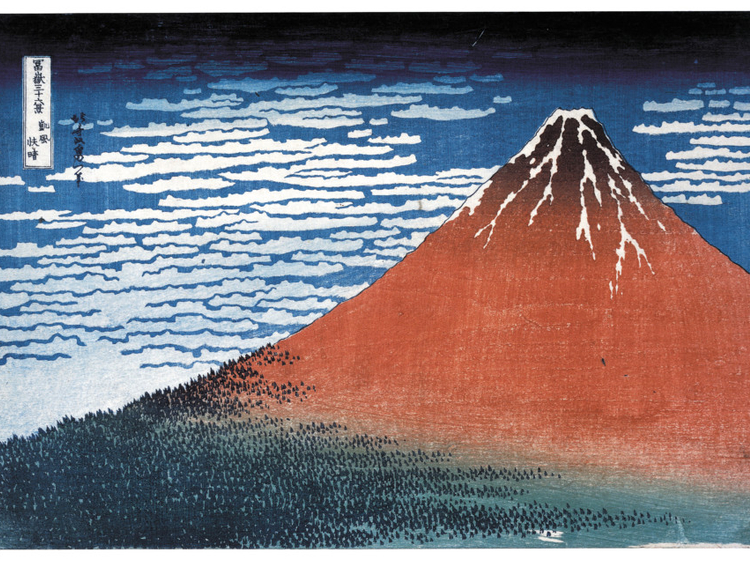

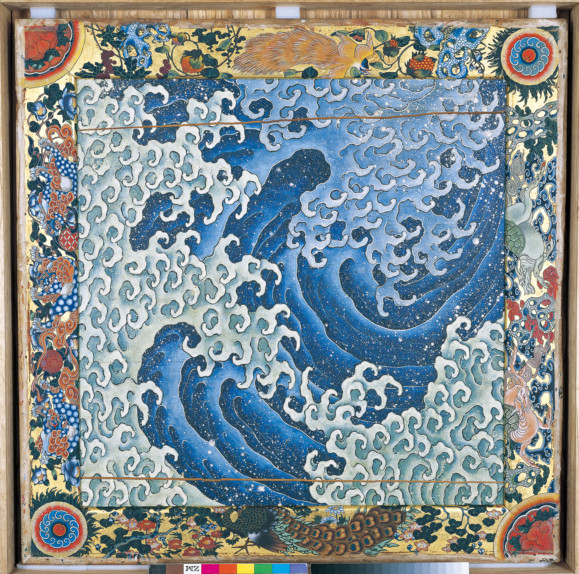

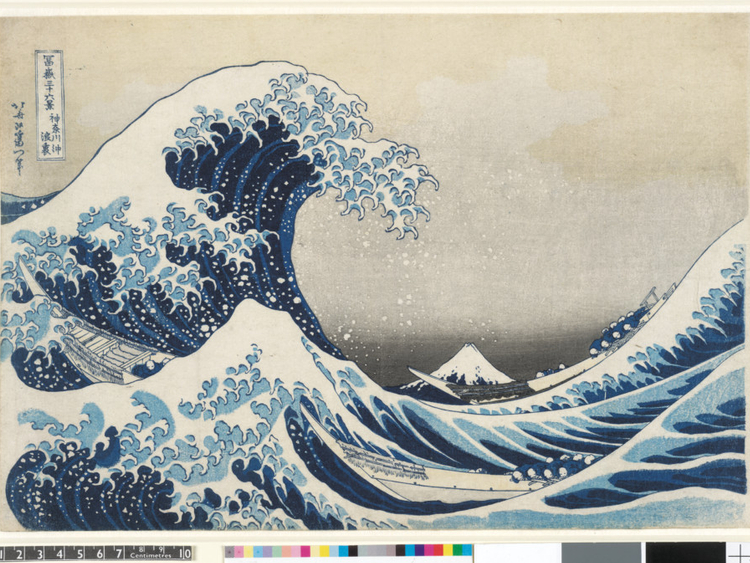

Nothing was a more powerful symbol of life and spirituality than Mount Fuji and no work of his is more familiar than Under the Wave off Kanagawa better known as The Great Wave. The frame is filled with mighty surging waves like tentacles reaching to the sky into which three boats delivering fish to the market in Edo (today’s Tokyo) buffet their way, heads down, fighting to survive.

The foam from the waves looks like snow falling on the small, almost inconsequential, triangle of the snow-capped Fuji in the background with the result that what should be the most prominent thing in the picture is almost dwarfed by the surging sea.

The Great Wave is one of his series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (published around 1831-33) and though the mountain is always in the distance the eye is inevitably drawn to its snowy cone.

The print tends to overshadow the others in the series but its popularity was such that as many as 8,000 impressions of each design were printed. What made it so celebrated was the revolutionary use Hokusai made of the pigment Prussian blue which had become available in large quantities from China, providing new shades and a greater volume to add to the traditional indigo.

The Views include a fisherman with his line, arced a little like the mountain itself, a group of pilgrims gazing at it from a viewing platform, through the circle of a barrel being hammered into shape by an artisan and catching the rays of the morning sun as three samurai gallop past in the foreground.

However distant and however small it appears Fuji dominated the landscape of central Japan - as it does today - not just a source of water to irrigate the rice fields but a sacred mountain, a powerful symbol of sustaining life. Where everything might be in a state of flux Fuji stood as a spiritual centre for the deity and as a talisman of longevity.

When Vincent Van Gogh saw The Great Wave he said: ‘The waves are claws, the boat is caught in them, you can feel it’ and he, like many Impressionist painters in Europe, was influenced by Japanese art once the country, which had been closed to foreigners for almost two centuries, was open in 1859. Claude Monet owned 250 Japanese prints, including 23 by Hokusai, which covered the walls of his house in Giverny. Edgar Degas was inspired by the thousands of sketches of fish, sumo wrestlers, geisha, and city-dwellers that Hokusai produced in his manga - printed sketch books not to be confused with contemporary adventure comic books - which sold in their thousands.

Just as he was an influence on western art he produced a collection of genre paintings in his earlier years - about 1824 to 1826 - which were commissioned by the Dutch East India Company.

In Japanese terms these were revolutionary works in which he adapted European styles such as the use of space and perspective which he might have absorbed from simple prints and illustrations in books imported from Holland.

They include Sudden Rain in the Countryside (1824–1826) which captures with a lively sense of movement a group scampering for cover under a brooding sky, their robes blown awry by the strong wind (revealing one startled bottom) and their umbrellas threatening to fly away. In the Flower-Viewing Party of the same period two elegant wives are on a spring outing to see the cherry blossom. The joy is in the detail; the patterns on their robes, the delicate tracery of the blossom, a servant with a red rug for them to rest on when they have a picnic. Wittily, Hokusai has the servants replicating the mannerisms of their mistresses.

It is hard to appreciate the incredible skill involved in the creation of these wood block prints known as ukio-e, in which genius of concept met precision of execution in techniques still used to day. First Hokusai would make a line-perfect drawing on very thin paper and add the detail with a fine brush - even the tiny dots of snow flakes or foam. The paper was placed face down on cherry wood and the cutter cut through the paper twice to leave thin ridges of wood in relief. With the blocks completed, printers applied ink using brushes and then lay a sheet of paper on top of the block, the printer rubbed the ink onto paper using a round, flat pad, called a baren.

The result can be dense and dainty. The deep, intense colour and composition of, for example, Cockerels and Hens (1833-34) contrasts with the delicacy of poppies, irises and plum trees, darting sparrows and languorous cranes. One of the most beguiling is Weeping Cherry and Bullfinch (1834) with the pink and white of the blossom and a perky bird upside down against a deep blue background. There are marvellously observed landscapes of rural and urban life in a series entitled Wondrous Views of Famous Bridges in Various Provinces, tremendous buccaneering heroes and diabolical demons from his One Hundred Ghost Tales. None are more eerie, than the skeletal ghost of Kohada Koheiji (About 1833) who is peering down on his sleeping wife, who, with her lover, had drowned him in a swamp. Bony fingers, staring eyes and malevolent smile - there can be no doubt of his murderous intent.

Hokusia’s restless urge to create resulted in 3,000 print designs over the span of his career and the publication of hundreds and thousands of works. As if to emphasise his relentless quest for immortality he changed his name more than 93 times and had lived in 34 different homes by 1834, although he always stayed in Edo.

We get a glimpse of his working habits and his relationship with artists daughter Eijo, who went by the name Ōi, from a drawing by a student. A quilt is thrown over his shoulders as he crouches on his knees to paint. His daughter looks almost disapprovingly, her hand resting on her long tobacco pipe. The print suggests he lived in some squalor. Apparently Hokusai stayed under the quilt from autumn until spring even though lice thrived in the warmth of the cover and in the corner of the room it is possible to espy a small area piled with rubbish.

As he hoped, his work became more powerful as he grew older and in his quest for ‘divine understanding’ he moved from the hugely technical print and block making to painting on silk hanging scrolls.

Gamecock and Hen (1826–1834) which he signed as itsu hitsu (‘Brush of Iitsu, the former Hokusai’) is one of his finest later works. A proud male cockerel poses in mid strut while a female stands behind him. The colours are bold, yet the detail brings them to life - from the dots on the red cockscomb and neck to the scales on the legs and talons and full feathers ready for flight.

By contrast, there are character studies such as the ebullient .Chinese Hero in the Snow (1843) - here he signs himself as ‘Brush of Manji, old man crazy to paint, aged eighty-four years’ - and The Third Princes and her Cat which captures her aristocratic formality thrown into confusion by an errant feline.

One of his greatest tributes to the Nichiren sect was painted in 1847. It shows the monk calmly reading from the a holy scroll while his supplicants cower in ecstasy below. A bristling seven headed dragon glares protectively from the dark clouds that surround the monk.

He must have known time was running out for him when he painted Dragon in Rain Clouds. It was 1849 and he signed the work ‘Brush of Manji, old man of ninety’ and with a seal that read: Hyaku - Hundred.

The dragon snakes out of a dense cloud and writhes into the heavens. All claws, scales and spines, it glares ferociously at a snarling tiger. The two paintings were intended to sit side by side; the dragon is the mythical creature of the east and of life-giving rain, the tiger of the west and of the earth.

For Tim Clark, the exhibition’s curator, and author of the authoritative catalogue that goes with it, the most ‘staggering feature of the dragon painting is that it was painted in reverse: the highlights on its head, claws, scales and spines are unpainted paper, and myriad tones of ink have been applied from light to dark, with jet-black ink flicked from the brush to add final excitement.’

He feels that the dragon’s intense expression and gaze ‘exude a living, almost human consciousness’ and perhaps its intensity is a recognition by the artist that he was in the last months of his life.

Right to the end he sought perfection and as a self-portrait of him as a wrinkled but vigorous eighty three-year-old suggests he resisted the inevitable. He exclaimed on his deathbed: “If only Heaven will give me just another ten years…” He paused. “Just another five more years, then I could become a real painter.”

He died on April 18, 1849 in the fourth month of his 90th year. By then he had become the ‘real painter’ he craved to be and through his work had indeed achieved immortality.

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.

Hokusai: beyond the Great Wave will run at the British Museum until August 13.