“London would be quite ugly if not for the fog.” So wrote Claude Monet, witheringly, from the Savoy hotel in 1901. It might be his last word on architecture. There is the city — specifically Waterloo Bridge, the Houses of Parliament and the grimy lead-shot factory opposite the balcony on which he is working — and there is the ever-changing play of climate, atmosphere and light around them. The buildings are just a pretext for painting the sublime.

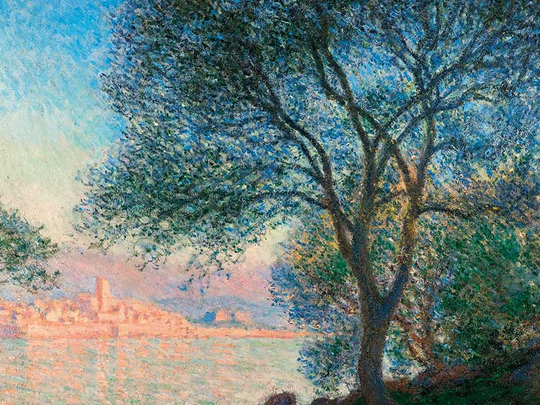

Weather and waterlilies, haystacks, poplars and seascapes: Monet (1840-1926) is not an artist of bricks and mortar. And even after seeing almost 80 paintings linking him with architecture, I doubt anyone will have their mind changed on this score. Of course he is indelibly associated with certain cities — there are seven paintings of London, eight of Rouen and nine of Venice at the National Gallery in London — but the show’s premise is at the very least counterintuitive. What does Monet have to do with architecture?

An early surprise is just how many different structures edge into his paintings. He paints a pitched fishing shack against a blustery sea near Le Havre and scarlet windmills cartwheeling across a flat Dutch horizon. One Parisian scene shows the side of an apartment block emblazoned with a massive advertisement, another centres on pedestrians milling along the stepped quays. A shadowy figure stands framed in a medieval doorway. Light filters through the sloping glass roof of the new Gare Saint-Lazare. In Giverny, in winter, the houses are like loaves of soft snow.

So far, it seems as if Monet is drawn to them all purely as shapes, combinations of rectilinear or triangular forms subjected to weather. And many of these built structures conjure classic Monet — cottages shaped like haystacks; bridge struts recalling stands of poplars or gondola poles. But it soon becomes apparent that architecture, both complex and primitive, offers Monet far more.

The Pont Neuf in rainy smog is a study in the innumerable different nuances of taupe, grey and pearl. A red-tiled roof sharpens up the predominant green of a landscape. A tiny house is like an index to the vast scale of the surrounding countryside. Monet is always preoccupied by what the eye can take in of each scene, near and far, at the fullest scope and all at once. An early driver, he motored so fast around Giverny the mayor gave him a speeding ticket in 1904.

The angle shifts, the light changes, the focus pulls from one view to the next — in sequence, the paintings almost move.

Architecture is a constructive element, so to speak, in Monet’s picture-making. It might be a way of taking the eye into or around a painting. A vision of clifftops, sandy shore and the great opening blur of the sea is pinned together, for instance, by a little steeple. It is not much more than a circumflex, but enough to orientate the eye. And one of the most exhilarating works in this show, The Hollow in the Cliff Path at Varengeville, shows the eponymous path as a hot, dark gully leading to a tantalising glimpse of wild blue yonder. The sense of anticipation is intensified by a cottage high on the cliff, a kind of human surrogate that seems to see, and even to be looking at, what we cannot — the glittering sea beyond.

The opening galleries are brilliantly selected to disrupt any conventional view of Monet’s evolution as an artist. In the early 1870s he is depicting windmills and Dutch houses, their gable ends traced in paint as stiff and thick as royal icing. And then here he is again, barely moments later, with a view of Amsterdam so hazy it’s nearly vanishing from the canvas; and you think it’s all there, the substantial world transmuted into air.

And then he jumps back, next decade, to lush strokes and oily accretions that build thick on the substrate; and even, occasionally, to quite detailed cobblestones. His trajectory was never straight from old realism to modern abstraction. Subject always dictates style. Steam in the Paris stations is diaphanous; damp sand at the new resort of Trouville is almost claggy; the Doge’s Palace melts like golden butter.

Monet worked in series early on. Two paintings from 1878 of the same picturesque Normandy church are paired together: milky and spectral, then grey and marmoreal. The building is immutable, but the effects of light, and memory, render it endlessly variable. A monumental weight upon the earth, it may nonetheless appear dreamy, though never quite mobile. In this respect, architecture remains distinctive in Monet’s work.

A notion, a recollection, an effect: his kind of impressionism does not deal in hard data. You couldn’t make an exact blueprint of the facade of Rouen Cathedral from any of the paintings in his great 1890s series. But you can deduce season, rainfall, the beauty of the circumambient air around the medieval structure; above all, the passage of time. Monet worked variously in an empty apartment and a ladies’ clothes shop opposite the cathedral, for up to 12 hours a day. The effects were so fleeting — a colour, he said, lasts no more than three or four minutes — that he might alternate between several different canvases. At 8am the cathedral shimmers in lemon light but the streets around it are still in blue shadow. Later that morning the sunshine turns golden and the traceries have higher definition. At dusk, the portals fill with gloomy purple shadows.

The angle shifts, the light changes, the focus pulls from one view to the next — in sequence, the paintings almost move.

Monet compared the cathedral to a cliff. Architecture is nature by other means for him. Each subject is a structure on which to hang the memory of a gradual dawn, a glowing form or fog. That is what this marvellous exhibition reveals through its clarifying emphasis on one limited subject — that for Monet, the experience of seeing always comes first.

And it is the same for the viewer standing before these ever-modern works. Rouen Cathedral, in rare loans from Belgrade and Cardiff, is translucent as fragile honeycomb or thick as rose and lavender blossoms, the surface muzzy and matt. In Venice, Monet floats on water. His cropping is so radical that the paintings put you right in the middle of the Grand Canal watching the buildings dissolve in the late light. What beauty there is in the art, the mind and surely the working days spent before the palaces and churches. People talk of the melancholy in the Venetian period, but it is not obvious to me. This late room is dreamily ecstatic.

Boat-loaders on the Paris quays, the tricolour blur of fluttering French flags, the dark chimneys of the lead-shot factory on the South Bank: there are many unexpected scenes in this show. But no matter how diverse, all are concerned with optical experience: the total effect on the eye, then the mind and memory. Each is a complete vision, not pieced together in fragments or details; the very antithesis of architecture in that way.

And from the Savoy, the bridges cross the Thames like the wooden structures over the pond at Giverny. Parliament becomes an apparition, its spikes softened by fog and dusk. They are all still there, the recognisable spans, domes and towers, but not as stony structures so much as an ethereal stage for the ceaseless and ever-changing play of Monet’s art.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Monet and Architecture is at the National Gallery, London, until July 29.