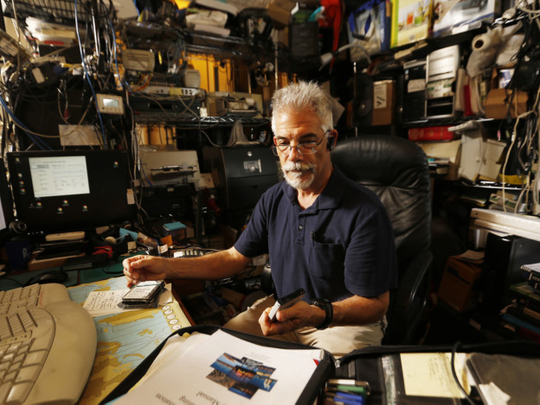

Washington: Edmund F. Biro still remembers how good his life was, before the financial crisis that nearly destroyed the economy 10 years ago.

The software engineer was earning about $85,000 (approximate Dh312,000) a year doing consulting work. He, his fiancee and her teenage son lived in a three-bedroom Chatsworth condo that had jumped to about $500,000 in value. Just in case of emergencies, his bank had set him up with a home equity line of credit.

“As far as I was concerned, things were going really well,” he said, “except I wasn’t aware of all the things that could go wrong.”

There were a lot of them.

The housing market crashed. The economy fell into recession. Then the collapse of Wall Street investment bank Lehman Bros on September 15, 2008 — 10 years ago this week — plunged the nation into the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.

Like many average Americans, Biro, now 61, is still struggling to get his life back in order. He earns less than half what he did in 2007 after much of his work dried up. His fiancee and son left, he said, when he could no longer afford to pay for college tuition and car expenses. And although he still has his condo, its value has dropped and he owes about $100,000 on the credit line.

“I’m very aware that I’m that close to being out on the street like those other poor unfortunates, and they’re everywhere,” he said.

Amid the chaos caused by Lehman’s collapse, the big banks got hundreds of billions of dollars in bailouts. Aggressive stimulus efforts by Washington officials injected trillions of dollars more into the financial markets and the economy, helping to end the recession, trigger record bank profits and fuel a historic stock market boom.

But there were no big bailouts for lower- or middle-income Americans.

About 8.7 million people lost their jobs, sending the unemployment rate soaring to 10 per cent. Housing prices dropped by a third nationwide from their 2006 peak — and even further in California — causing as many as 10 million people to lose their homes.

By 2012, more than 1 in 7 Americans — a staggering 46.5 million people — were living below the poverty line.

The economy now has regained all the lost jobs and more while housing prices have rebounded in most of the country. But many of the deep wounds have yet to heal.

Median household income, adjusted for inflation, has barely budged over the last decade while the incomes of the wealthiest 5 per cent of Americans have increased 10 per cent.

The crisis stunted US economic growth so much over the last decade that it has cost every man, woman and child in the country $70,000 each in lost income, according to calculations this summer by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

“While everyone labored mightily to stabilise and support the banks and Wall Street, not nearly enough was done to support the American people and the American economy in the wake of the crash,” said former California Treasurer Phil Angelides, who chaired a national commission that studied the causes of the financial crisis.

The uneven recovery, which exacerbated a growing income gap that began in the 1970s, has had profound ramifications.

The anger caused by the bailouts and the failure by federal officials to send any top Wall Street executives to jail for causing the mess sparked outrage on both ends of the political spectrum — helping propel Donald Trump’s populist rise to the presidency.

The architects of the government’s response to the crisis have defended their actions even as they expressed concern about the fallout for average families.

“We were focused on staving off disaster,” said Henry M. Paulson Jr, Treasury secretary under former President George W. Bush. “None of us can feel anything but terrible about the suffering that is going on. I would just argue that not all of this is related to the financial crisis.”

But much of it is related to a disaster that had been gathering for months before sharply escalating with the collapse of Lehman Bros, a storied Wall Street firm that Paulson and other federal officials had frantically tried to save.

It was a crisis that, in retrospect, had its origin in policy and regulatory failure — along with a healthy dose of old-fashioned greed.

House of cards

The housing market boomed in the early 2000s amid low interest rates and a deregulatory environment that led to indiscriminate — and often predatory — lending to subprime borrowers with low credit scores and questionable abilities to repay.

Americans such as Celia de La Rosa, 65, discovered they were able to buy homes they never thought they could afford. After the value of her condo more than quadrupled to about $250,000 during the boom, De La Rosa sold it and bought a three-bedroom house in Covina for $610,000.

Although she had a strong credit score, De La Rosa was earning only about $80,000 a year, making her mortgage payments of about $2,500 a month a stretch.

“I take full responsibility. I should never have signed on the dotted line when I bought the house, but everybody said, ‘Go ahead, buy the house,’ “ De La Rosa said.

“I had no reason to think that maybe the housing market would crash. Everybody’s houses were selling,” she said. “Then Wall Street started having all these problems and it all trickled down.”

Banks and a new wave of subprime lenders had injected steroids into the financial system, packaging mortgages into complex securities — often with top credit ratings that did not reflect their high risk — and selling them to investors.

To protect against a default on the securities, investors bought another type of sophisticated product called a credit default swap. Trillions of dollars exchanged hands. An enormous financial house of cards was constructed on a shaky foundation of subprime loans and federal regulators failed to see it.

When the housing bubble burst in 2006 and homes tumbled into foreclosure, the fallout spread like a virus. Countrywide Financial Corp. of Calabasas, IndyMac bank of Pasadena and other subprime lenders suffered huge losses and were sold or collapsed starting in 2007.

Federal Reserve officials intervened in March 2008 to financially back the sale of Wall Street investment bank Bear Stearns, which was on the verge of bankruptcy because it was laden with toxic mortgage assets.

In early September 2008, federal regulators also seized Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac , the teetering government-sponsored housing finance giants that owned or guaranteed about half the total outstanding US mortgages.

But Paulson, Fed then-Chairman Ben S. Bernanke and Timothy F. Geithner, then-president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, drew the line at Lehman and allowed it to fail.

The stock market meltdown that followed forced Paulson and Bernanke to warn congressional leaders that dramatic action was needed to prevent the complete collapse of the financial system. Congress passed the $700-billion Troubled Asset Relief Program shortly afterward.

The original goal was to purchase toxic mortgages from the banks. But Paulson decided quicker action was needed. He opted to inject money — ultimately nearly $250 billion — directly into hundreds of banks.

“We thought that was the best way to protect the American public,” said Paulson, who acknowledged in a meeting with reporters this summer that the policy “was totally ineffective in having the American people understand that what we were doing was for them and not for Wall Street.”

The bailouts defied a deeply held American principle: Those who get into trouble in the free market must suffer the consequences.

“When you violate such a core belief, people get mad,” said Neel Kashkari, the Treasury official Paulson tapped to run TARP and who is now president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. “I think we did the right things, but now we’re still paying the price.”

Experts broadly agree that the bailouts worked to halt the financial crisis and stabilise the banking system. But that was only the first battle.

Crashing down

The crisis dramatically deepened the recession that started in December 2007, and that was a big blow to average Americans even if they hadn’t bought a new house or refinanced an old one.

But with the worst of the crisis over by the end of 2008, it became more politically difficult in Washington to provide additional taxpayer assistance.

One of the first moves by President Obama after taking office in January 2009 was to push through Congress — with almost no Republican support — a $787-billion stimulus package. It included temporary tax cuts, extended unemployment benefits, aid to struggling states and infrastructure projects to try to boost the cratered economy.

Economists said the stimulus was vital to the economic recovery. But some critics, such as Robert Reich, a labor secretary under President Clinton, argue the legislation was a half-measure.

“I think it wasn’t enough for average workers, people who lost their jobs or whose income suffered or who lost their homes or their savings,” said Reich, a UC Berkeley professor who wrote about income inequality in his 2015 book <Saving Capitalism>.

The day after Obama signed the stimulus bill, he tried to do more. He unveiled a $75-billion initiative — using TARP money — to help struggling homeowners get reduced mortgage payments by lowering their interest rates.

CNBC’s Rick Santelli blasted the idea as a move to “subsidise the losers’ mortgages” in an on-air 2009 rant that helped launch the tea party movement.

Economist Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a member of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission who had been a top advisor to the 2008 presidential campaign of Senator John McCain, said such a bailout for homeowners wasn’t possible.

“There was no large-scale macroeconomic housing plan that was politically feasible,” Hotlz-Eakin said, arguing it would have amounted to “a transfer of wealth to one set of people who were underwater from the others.”

The Obama administration pushed ahead with mortgage modification programmes anyway, but they struggled to gain traction amid bureaucratic problems at participating banks and consumer scams. In the end, the aid delivered to homeowners was less than half the promised $75 billion.

After the value of her Covina home dropped to $450,000 from the $610,000 purchase price and her salary was cut, De La Rosa sought help from one of the initiatives, the Home Affordable Refinance Program. An attorney asked for $3,000 to help with the application, then disappeared, she said.

De La Rosa eventually was able to secure a modification that lowered her interest rate to 2 per cent from 7 per cent for five years. It helped her stay in her home.

“It was very, very hard to swallow that I couldn’t pay my bills and I was getting further and further in debt,” she said. “It was not a fun time.”

The bailout fund and stimulus legislation mostly tapped out congressional help, so the Fed tried to boost the economy with unprecedented and controversial steps.

Fed officials lowered their key short-term interest rate to near zero in late 2008 and held it there for seven years. And the Fed purchased about $4 trillion in mortgage-backed securities and Treasury bonds to push down long-term interest rates in a maneuver known as quantitative easing.

The policy meant investors had to turn to the stock market for significant returns, starting a record bull market that has seen the broad-based Standard & Poor’s 500 index increase by about 125% from where it was just before the crisis.

“The Fed is not deliberately trying to skew the benefits to the top 1%, but one of the effects is that is the consequence,” said Adam Tooze, a Columbia University history professor and author of a newly released book, <Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World>.

Tides of change

The stock market’s quicker recovery than the housing market’s amplified income inequality for a simple reason: Most average Americans don’t own much in stocks, despite the availability of 401(k) plans.

A study this summer from the Opportunity and Inclusive Growth Institute at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis analysed decades of data to show that the primary source of wealth for middle-class Americans is their home, while the main asset of the top 10% of earners is stocks.

Climbing home prices from 1950 to the mid-2000s helped the middle class hold its own relative to the upper class. The collapse of the housing market and the financial crisis altered that, producing “the largest spike in wealth inequality in postwar American history,” the study said.

Wage growth also has been stagnant for many people despite historically low unemployment. The median household income was $58,149 in 2007, according to the Census Bureau. In 2016, the most recent year available, it was $59,039 — just $890 more — after adjusting for inflation.

Anger over the growing income disparity, as well as the bailouts, helped spark Occupy Wall Street — the political left’s version of the tea party movement, which declared it represented the other 99 per cent of Americans.

“The tea party movement was angry with government for doing the bailout and the Occupy movement was angry with the banks for gambling with people’s money and causing the need for the bailout,” Reich said. “They were two sides of the same coin. A lot of that anger and distrust toward large institutions remains to this day.”

Biro, the Chatsworth software engineer, feels it.

He recalls how the bank representative did all the paperwork for his line of credit right there in his living room.

“I remember saying, ‘Wow, that was easy,’” he recalled.

A decade after the crisis, Biro said that working people like him “didn’t get nearly the benefit” out of the rescue that the banks and the wealthy did.

“I think the game has changed,” he said, “and that’s kind of scary.”