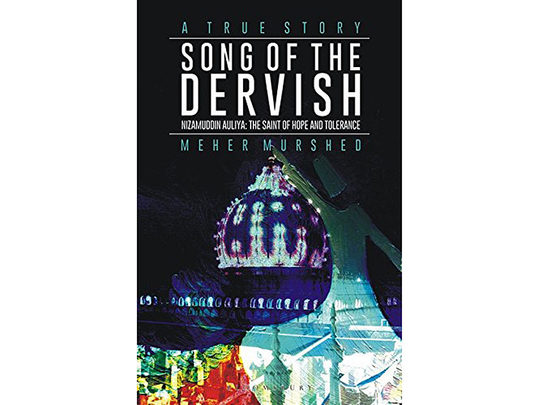

Title: Song of the Dervish

Author: Meher Murshed

Publisher: Bloomsbury India

Pages: 242

‘Mohe pir paayo, Nizamuddin Auliya...’: The saint and his grace...

That is from one of the subcontinent’s best-known qawwalis honouring one of its most venerated Sufi saints but its true worth is seldom realised. In it, the singer is addressing his own mother as he praises his spiritual master, who was himself known for paying immense respect to his mother, laying his head regularly in her feet -- in life and in death.

And Nizamuddin Auliya’s respect for women was not restricted to his own mother. The saint, as we learn in this evocative account of his life and impact, once told an adherent who came to see him with his four daughters, that those with even one daughter “had a barrier against hell” and with four, he was well protected.

There is much more about this exemplary Sufi, but author Meher Murshed, whose own background offers an example of the synthesis the Sufis sought to foster in the subcontinent (and persists -- despite efforts of bigots from both sides) doesn’t concentrate only on him.

While featuring Nizamuddin’s other illustrious Chishti forebears and successors (Khawaja Moinuddin, Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, Baba Farid Ganjshakar and Chiragh Dehlvi), and his prominent disciples beyond Amir Khusro, he also goes further to trace the stories of those in our times who have felt the grace of the saint.

Murshed, who admits his first encounter with Sufism was hearing the qawwali “Man Kunto Maula” (closely identified with the Chishtis) as a five-year-old, and other versions later, says “strange circumstances” took him to Nizamuddin’s shrine one winter night in 2009 where he heard it again and it left him “mesmerised”. He sought to research it but it took him on a totally different path.

“My quest led me to uncover a riveting story of love, tolerance, compassion, hope and deceit,” he says, but notes what struck him most was the seeming incongruity of a dervish who scorned wealth and power having a courtier and warrior as his favourite disciple.

It is this mystery Murshed seeks to plumb, while introducing a new generation to the qualities of the Sufi saint that endeared him in his own era -- and ensures he still draws adherents seven centuries hence.

Murshed, a journalist by profession, begins with the later aspect -- the story of a train passenger, very badly injured while trying to resist a robbery, but getting a vision and a curious chain of circumstances that leads to his life being saved.

It is followed by more accounts of those who found solace -- and ultimately a solution to their plight -- after visiting the shrine and beseeching the saint’s help. Some of them will, however, leave your mind reeling, and a couple or so towards the end are a little puzzling.

All these accounts, mostly of our times (though some go as far back as the 1950s) but quite far dispersed in space, are interspersed with Nizamuddin and the Chishtis’ story and their times, as well as some ruminations on how the “miracles” attributed to the Sufis sit with modern thought, say Einstein’s belief that there was no “personal god”.

And then aptly for someone who was introduced through music to the Sufi who favoured “sama” (musical ceremony) and the “wajd”, or religious ecstasy it can induce, and oversaw the birth of qawwali, there is quite a fair bit of music.

This spans the stories of a Canadian teenager who left his home on a spiritual search and transformed into Tahir Faridi Qawwal, the legendary Sain Zahoor, Ali Hamza and Ali Noor, and Rohail Hyatt, the brain behind Coke Studio Pakistan, among others.

One problem, however, with this otherwise admirable book is that there is too much repetition. Happenings in not only the saint’s life but those around him (especially Jalaluddin Khalji), as well as those who claim they have benefitted from the saint’s abiding generosity, crop up multiple times in the text, aausing some vexation.

And, while Khusro’s lyrics are featured, they -- save the first couplet of “Nami Danam..” -- are in translation, which may give their meaning to non-Farsi/Hindustani-knowing readers but fail to convey their sonorous effect.

However, these do not detract from the enduring message of this book -- a message more needed at present.