If prizes are about boosting the book trade then this is not a good list: determinedly unstarry in the first place, it has jettisoned even those namecheck authors who had made the longlist.

But if prizes are about generating curiosity and discussion, then it is an excellent line-up that asks a series of important questions, such as how serious is satire? And when is a short story not a short story?

Everyone loves a David and Goliath story, so first reactions have focused on the historical crime writer, published by a tiny Scottish imprint, who stared down big hitters.

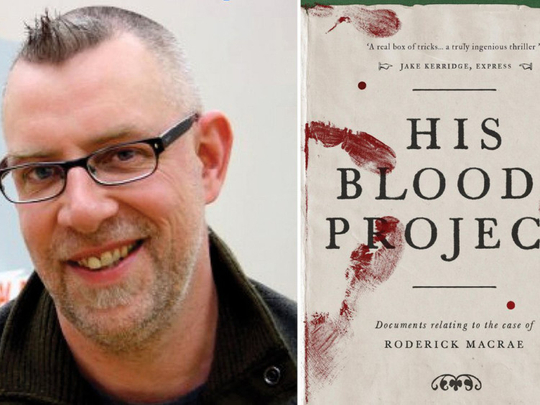

Graeme Macrae Burnet’s second novel, His Bloody Project, was released in paperback in November and ignored by all but one national newspaper. But it will be reissued in hardback next month. Subtitled Documents relating to the case of Roderick Macrae, it satisfies the Booker jury’s quest for books that “take risks with language and form”, by wrapping the memoir of a teenage crofter, awaiting trial for triple murder in Inverness in 1869, in the faux-diary of the author who “discovered” the tale while researching his own Highland roots.

“I have largely restricted my interventions to matters of punctuation and paragraphing,” explains the narrator. There’s a healthy dose of Kafka as well as Flann O’Brien in Roderick’s account ...” wrote Justine Jordan in the Guardian. It is one of two contenders that could loosely be classified as genre, along with Ottessa Moshfegh’s psychological thriller Eileen, the only first novel to survive the cut.

Though I admired Ian McGuire’s seafaring yarn The North Passage, I can see why His Bloody Project pipped it to this shortlist: it is an interesting hybrid of crime thriller and historical fiction. It is about as far as it could be from the other historical novel on the list, Do Not Say We Have Nothing, by Madeleine Thien is a brilliant but demanding meditation on language and memory set over half a century of Chinese history.

Centred on the oppression of musicians from the cultural revolution to Tiananmen Square and beyond, it takes its name from the Chinese translation, via Russian, of a line from the socialist anthem The Internationale. Thien, the daughter of a Chinese mother and Malaysian father, who was born in and lives in Canada, is no stranger to hard history: her previous novel, Dogs at the Perimeter, dealt with the Cambodian genocide.

Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, premised on the disappearance of a whole city from the map of California, raises the flag for satire in a prize not known for its sense of humour. Very different again is Hot Milk, from Deborah Levy, who makes a teasing addition to a growing body of pared-back novels by women on the complexities of the human condition.

Where Levy focuses on the experience of a young woman, David Szalay looks at masculinity. All That Man Is unfolds in a series of pen portraits. Is it a novel? The critics who reviewed it for the Guardian and Observer both concluded that it was really a series of short stories, reopening a debate that has resurfaced from time to time ever since David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas hit the shortlist back in 2004.

— guardian.co.uk (c) Guardian News & Media Ltd, 2016