Plato once commented: ‘Only the dead have seen the end of war.’

The nuances of battle, ensuing bloodshed, decisions that change the course of battle and at times, the world, are details that fighters either take with themselves or are learnt vicariously through reports.

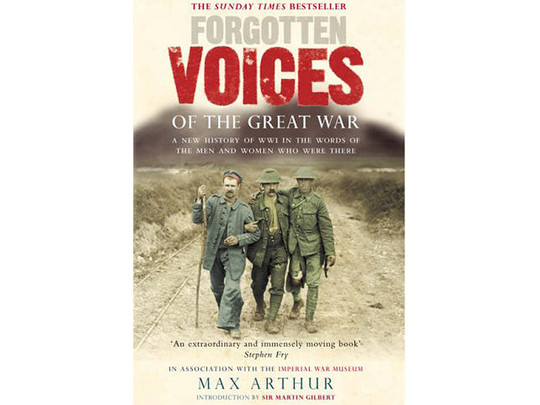

‘Forgotten Voices of the Great War’ grapples with the experiences of World War I through memories and emotions of men who lived to tell their stories. Using voice recordings housed in the Imperial War Museum, Max Arthur reveals the success and struggles, delight and dismay of war veterans from English, French, Australian, US and German camps.

More than strategic shifts arising from military stewardship, the book captures the physical and emotional cost of a war that few expected to last beyond Christmas of 1914. The book, then, is not for the faint-hearted. Descriptive narrations of physical damage are rife, explained in words that display an uncharacteristic valour yet utter grief and confusion. Some of the harshest times were spent not facing a barrage of bullets, but waiting in trenches that were breeding grounds for infection and sickness.

Readers are introduced to these prolonged moments of inactivity; a periscope into the minds of men living the uncertainty of a war, one harrowing moment and battle at a time.

The book also mirrors a paucity of awareness in the world outside. In the words of a London Regiment member on leave: “They knew that people came back on leave covered with mud and lice, but they had no idea of what kind of danger we were in.”

A pronounced naiveté and inability to grasp the dynamics of war is a recurrent theme in early chapters. Veterans reminisce their conscription days when as boys - no more than seventeen or eighteen - they eagerly filled up recruitment centres in the hopes of joining the army. Any deficiency was filled shrewdly, as Thomas McIndoe, a Private in the Middlesex Regiment, demonstrates in his story. After being turned down in the first attempt, a visibly underage Thomas dupes the recruiting officer into enlisting him by donning a bowler hat.

Remainder of the pages, in earnest, speak of the men’s abrupt transition into hardened manhood through a gruelling war.

Beyond ghastly wounds and dungeon-like trenches, battalions salvaged fleeting moments of entertainment. A Lieutenant from Warwickshire Regiment recalls converting an unshelled ground - a rarity - into a cricket outfield. The friendly game with Australian battalions ended without a result; the Germans - bemused as they may have been by inexplicable movements - heavily shelled the men, killing some and injuring others. In war, unlike sports, people seldom kept scores.

The book ends with a series of battles leading up to the armistice signed on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918. While the landmark moment that ceased fighting has been easy to remember, the collection of narratives make a compelling case against a forgettable war.

‘Forgotten Voices of the Great War’ urges us to look within as we look at nations embroiled in perpetual conflict today. The tools may have changed and so have the motives, but hollowness rings throughout war - be it in the words of those who lived to explain, or listless bodies of those who did not. This is poignantly captured in the book’s last account, an anti-climax of sorts to welcome the end of war - “I should have been happy. I was sad. I thought of the slaughter, the hardships, the waste and the friends I lost.”

— The reader is a writer and public relations executive based in Dubai.