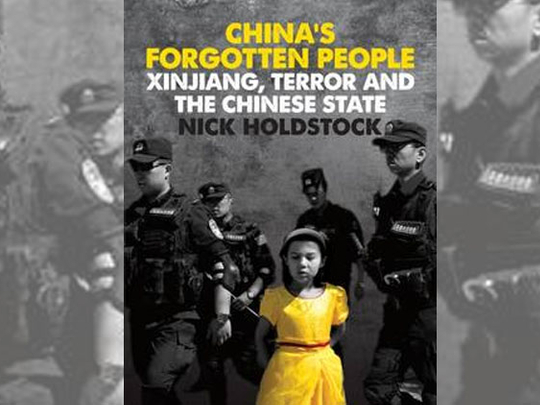

China’s Forgotten People: Xinjiang, Terror and the Chinese State

By Nick Holdstock, I.B. Tauris, 288 pages, $25

China, the world’s next superpower. China, the world’s factory. China, the world’s last major one-party state. All these are euphemisms that we have heard over and over again. What has been much less in the limelight is the plight of China’s several minority groups.

Journalist Nick Holdstock attempts to correct this balance with his book “China’s Forgotten People”, in which he narrates the plight of the Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, the main ethnic group in the country’s largest province on its northwestern frontiers. As someone who has extensively travelled in the region for 15 years, Holdstock’s book gives us a rare glimpse into the land and its people, and how the policies of the Chinese state have led to an extreme sense of alienation among the Uighurs, with some of them turning to radical steps and violence.

In narrating the rise of the two Asian giants, India and China, one very often comes about the comparison how both began from similar impoverished conditions in the 1940s, but China managed to far outrun its southern rival in all aspects of development. One factor which is seldom taken into account in this journey is the ethnic issue.

China, with its billion-plus population, has a single ethnic group — the Han — which constitutes more than 90 per cent of the country’s population, and this cohesiveness has been a pivot of the development strategy of the state. India, in contrast, with its numerous linguistic and ethnic groups, and the differences of opinion among them, has found it more difficult to integrate these voices into a single one for national development.

This overwhelming numerical superiority of the Han has been a major factor in the Chinese state’s policies in the provinces and their minority populations. Xinjiang, too, has felt its effects. Holdstock narrates how the Chinese state has systematically pushed Han Chinese into the region, with the result now that almost 40 per cent of the province’s population is now composed of the Han. This, along with the lack of opportunities for the Uighurs, has resulted in a deep sense of discontent and alienation among them, which has often spilt over into violent incidents.

Drawing from the past, Holdstock has narrated the history of the Uighurs in a fairly descriptive fashion, starting from their origins as a confederation of Turkic peoples in the 8th and 9th centuries. He goes on to narrate the impact of the arrival of Islam and how it blended with the existing shamanic practices of the area, which coalesced to form the present religious and ethnic practices of the Uighurs.

From that point, the history of the region is taken on further into the Middle Ages and the times of the Qing dynasty, ending with the republican and finally the present communist era. At each of these phases, Holdstock notes the plight of the local people under successive regimes.

In the recent era, Holdstock elucidates how systematic measures by the Chinese state have led to increasing alienation among the Uighurs. Of particular importance is the banning of “mashraps”, a traditional form of social gathering where the older generation imparted social, moral and cultural education to the young. The government’s reasoning was that these meetings were being used to incite sectarian and fundamentalist sentiments.

Also, the government, in an attempt to promote tourism, has opened up a number of “mazars”. However, in the process, tourists were allowed to smoke and drink at these places, which obviously angered the locals. In another contradictory move, the government banned Ordam, a festival that was celebrated at the “mazar” of 10th-century martyr Ali Arslan Khan.

A series of violent incidents in Xinjiang over the past couple of decades have been regularly ascribed by the Chinese authorities to the rise of fundamentalism and terrorism in the area. Holdstock holds that such incidents are mostly a reaction to the policies that the state has followed in the region, which has left the locals increasingly frustrated and angry.

Holdstock has done a commendable job bringing out the plight of the common Muslim Uighur, especially when seen in the light of tight media controls in China. However, to an extent, I would think Holdstock falls into committing the fallacy of what is termed “participant observation”, where a researcher conducts his or her study living among the subjects of research. This often tends to cloud the person’s judgment.

I say this as while there are numerous instances detailing the Chinese state’s policies in Xinjiang, which Holdstock believes have led to the frustrations and violent outbursts in the area, there is no description anywhere in the book as to what steps, if at all, the Uighur community is itself taking to integrate with the Chinese mainstream.

In the present geopolitical situation, I don’t think anyone in the right frame of mind would be thinking of a secessionist movement in Xinjiang, despite all its historical connections with the Turkic peoples. Thus the future of the Uighurs, at this point of history, remains with China and the solution to its alienation has to be found within the Chinese state itself.