Even the hand rails on the stairs that lead to the toilets are heated in the fantastical art gallery designed by architect Frank Gehry for the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris.

Maybe that’s what one should expect from a company whose customers inhabit a world of luxury and extravagance in which handbags cost almost £2,000 (Dh10,950) and scarves £500. But extravagant does not begin to describe a building which — as one critic put it — looks like “a crystal palace that is in the middle of an explosion.”

On March 30, the Foundation staged the third of its inaugural exhibitions since its opening in October 2014. Called “Keys to a Passion” it is a collection of modern art with works from familiar faces such as Picasso, Matisse and Rothko.

The building, which cost $143 million (Dh525 million), has been a long time coming. In 2001, Louis Vuitton owner Bernard Arnault was persuaded by his special adviser Jean-Paul Clavierie to visit Bilbao in Spain and see for himself Gehry’s extraordinary Guggenheim Museum. It was the “haute couture” building Arnault desired and one that would more than match the foundations established by rival companies such as Prada in Milan, Ferragamo in Florence and Francois Pinault in Venice.

Where to build? Luckily, LVMH the luxury goods conglomerate and parent company to Louis Vuitton owned land in the sylvan acres of the Bois de Boulogne, which included a rundown bowling alley and the Jardin d’ Acclimatation, a quaint formal garden with an “Enchanted River,” a folly and pagoda created by the Emperor Napoleon III in 1860.

The press release claims that the gallery “blends in seamlessly with the natural environment” — which is exactly what it does not. Gehry has come up with all the audacious tricks and treats, twists and turns that typify his work and far from blending in, this is a mighty ship — a veritable galleon in full sail, its spinnakers — all 12 of them — straining in the gale. While the new building had to stay within the same 11,000 square metres of the old alley and be of the same height that restriction did not apply to the glass canopies that appear to soar off into the sky, swooping and hovering, held aloft by massive steel and timber struts that stand out from the solid cube constructions — the “iceberg” — at the centre.

While the exterior is a work of art in itself, the interior — or rather the actual galleries — are functional affairs without a curved wall to disturb the hang.

To reach the temporary exhibitions one takes an escalator to the basement, looking as one goes over a streamlined concrete grotto with a commission by Olafur Eliasson, “Inside the Horizon (2014)”. Columns of varying widths placed along a walkway with two of the sides covered in mirrors and the third in a yellow glass, reflect in a pool whose waters ripple outward from a cascade.

The new exhibition has loans from several galleries including Tate Modern in London, MoMA, New York and from three in Russia, The Pushkin, Moscow, the State Russian and the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg. It is divided into four categories — Subjective Expressionism, Contemplative, what the organisers call Popist and Music.

The curator of the exhibition, Suzanne Pagé is keen to stress that it is necessary to make an emotional dialogue requiring time and concentration to view the show and explains that the artists on show were chosen because they had broken the rules of art — they were iconoclasts.

Iconoclasts. It is the word that appears time and again in the company literature to describe itself and its products and, of course, Gehry’s work of architectural “haute couture.”

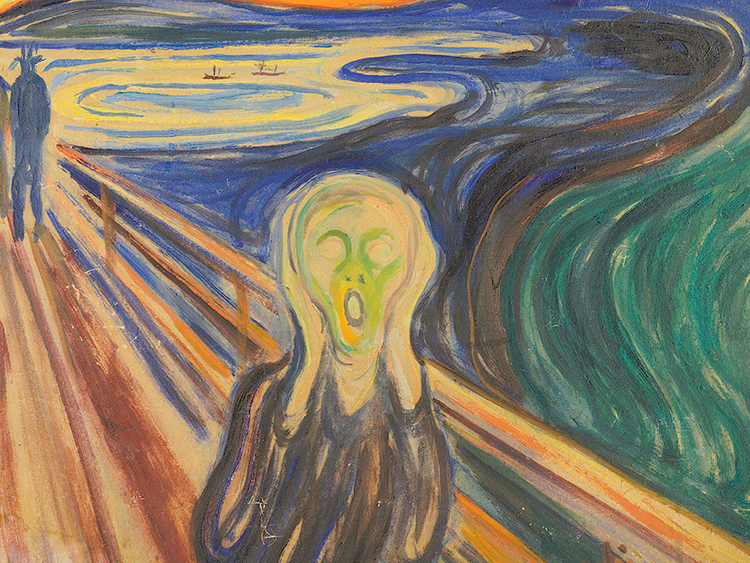

Supported by a mightily comprehensive catalogue with substantial essays on each artist by different experts, the exhibition opens with Subjective Expressionism which has two studies by Francis Bacon from 1949, Otto Dix’s unflinching “Portrait of the Dancer Anita Berber (1925)”, wild child of her day which captures both her brazen notoriety and her dissipated beauty and the first version of Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” from 1893 or 1910.

Perhaps less known is Finnish painter Helene Schjerfbeck (1862-1946) with a series of self portraits between 1915 and 1944, which are unflinching and ultimately rather gruelling. Her face metamorphoses from that of an unlined young woman disintegrating into what amounts to her own mask of death painted a few weeks before she died.

No section labelled Contemplative would be complete without a Monet and here is the familiar “Blue Water Lilies” (1916-19) along with “Summer” by Pierre Bonnard (1917) and the intensity of Mark Rothko’s “No 46” (Black, Ochre, Red Over Red) 1957.

There are three Picassos which were inspired by his illicit relationship with the 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter and Constantin Brancussi’s “Endless Column”, Version (1918) which some consider to be a touchstone in modern culture. Less well known are a marvellous series of “Lakes” by the Finn Akseli Gallen-Kallela and the Cézanne-esque lakes and mountains of the Swiss Ferdinand Hodler.

One of the most striking contributions comes from the State Russian Museum with Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square, Black Circle, Black Cross” (1923). It is a rare sighting of the three most potent examples of his Suprematist art which were first shown in Leningrad (St Petersburg) in 1926.

In the room given to Popism — a sort of early populist art — there are striking pieces by Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger and less appealing, Francis Picabia whose photographic and cinematographic images seem now to be merely cheap and exploitative.

The fourth section, Music, has the dashing “Panels For Edwin R Campbell” (1914) by Vasily Kandinsky which was commissioned by Campbell, the founder of Chevrolet Motors — another wealthy individual who sponsored art. “The Dance” (1909-10) by Henri Matisse positively leaps off the wall and Gino Severini’s “Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin” (1912) captures the surging energy of a Parisian dance hall.

Take the lift to the fourth floor, walk back down, through the struts and curving canopies to discover the terraces and galleries, which house some of M. Arnault’s private collection such as Sigmar Polke’s “Cloud Paintings” (1989), June Nam Paik’s “TV Rodin” (1976-78), a cast of the Thinker, studying himself in a video monitor via closed circuit television. Visitors can peer over the sculpture’s shoulder and appear on the screen. One landing is peopled by a group of works by Giacometti and another has the strange “Where The Slaves Live” by Adrian Vilrar Rojas, a cylinder of organic as well as inorganic materials which changes as the plants grow.

Concentration wanders as each step reveals another perspective of the steel and glass edifice — the huge bolts, the timber struts, the curves of glass, often diaphanous because of the material used to strengthen it — and in the gaps; the woods, the tower blocks of La Défence business quarter and, framed by two shards of glass, the Eiffel Tower.

The company website talks about its “daring and genre defying audacity” and, above all, its journey into the future. That this is a collection that is “both universal and personal, and in the cherished traditions of the house, once again defies expectations.”

It could be a reference to the art, it should be about the gallery. But no, it is about the monogram, the famous letters LV, which was first used in 1896. A Louis Vuitton project entitled “Celebrating Monogram” has commissioned works by creative iconoclasts such as Christian Louboutin, Cindy Sherman, Frank Gehry and Karl Lagerfeld.

It’s that word again. The huge glittering silver LV which dominates the front of the gallery reminds us that the art, the gallery, the handbags and the scarves are all about defying the genre. Icons all.

“Keys to a Passion” is on show at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris until July 6.

Richard Holledge is writer based in London.