For some it is a small revolution. For others, a minor victory in a long drawn-out war of attrition.

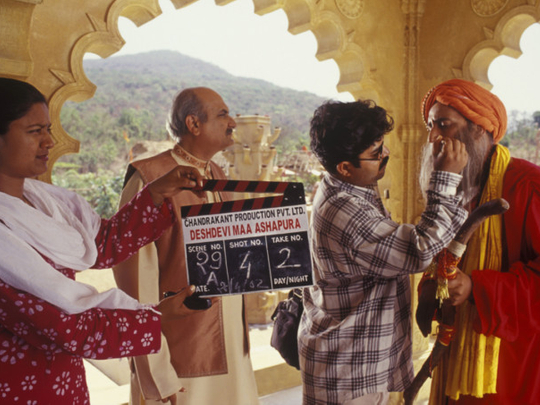

On Monday, India’s supreme court is to end a 59-year-old de facto ban on women working as makeup specialists on Bollywood film sets. The change is the result of a five-year legal campaign by Charu Khurana, a makeup artist from Delhi.

“Somebody had to take the initiative. This is the 21st century. All over India women are joining all spheres on an equal footing,” the 32-year-old said.

The regulation, which has no legal basis, had been maintained to protect the jobs of male makeup artists, film workers’ unions have admitted.

Women are permitted to be hairdressers, with a series of further restrictions on where and when they can work, but not makeup artists.

Khurana filed a private petition, claiming discrimination. Comments by the judges at a hearing last week indicated they agreed.

“Why should only a male artist be allowed to put on makeup? How can it be said that only men can be makeup artists and women can be hairdressers? We don’t see a reason to prohibit a woman from becoming a makeup artist if she is qualified... We are in 2014, not in 1935,” Justices Dipak Misra and UU Lalit were reported as saying.

Khurana’s effort is one of many by campaigners trying to force new freedoms for women in what is still a deeply conservative society. She launched her campaign after being fired and forced to pay a Rs25,000-rupee (Dh1,495) fine to the union after a raid on the set of a film she was working on as a makeup artist.

India’s £1.3 billion (Dh7.6 billion) film industry is the largest in world by ticket sales, producing between 300 to 325 movies a year. Although there are no official figures, trade analysts say the Hindi-language industry, which is based in Mumbai, employs more than 250,000 people, most of them contract workers.

In terms of its product and structure, Bollywood is said to represent and reinforce contemporary India’s concerns, dreams and values.

“When I started going to sets there were often only four women: the leading actress, her mum, the hairdresser and me. There is a huge change. It really is a reflection of the new India,” said Anupama Chopra, a Mumbai-based film critic and expert. But if women were working as composers, cinematographers and “in other previously all-male bastions”, top level jobs remained the preserve of men with only one female studio owner, she added.

There is also a significant gap in pay for male and female stars, with many men now co-producing films while women tend to be “hired”.

Advaita Kala, one of the few younger women who are successful writers in the industry, said changes such as allowing female makeup artists indicated progress but there “was a long way to go”.

“This year there have been a number of films with female lead [characters] and that’s a first. Usually you are lucky if there is one. It’s still very much a boys’ club,” Kala said.

Many major Bollywood films still feature an “item girl” — a female star who has no connection to the plot who performs a dance routine. “Only [in India] would the term ‘item girl’ find legitimacy. Cinema is still dominated by the male gaze. Our films are feeding us the idea of objectification as empowerment. There are still lots of battles to fight,” said Kala.

A recent United Nations-sponsored survey analysed gender roles in popular films released across the 10 most profitable territories internationally between 2010 and 2013. It found a higher than average level of female characters in Indian movies shown semi-nude, with few women in significant speaking roles or portrayed working.

In India, out of a sample size of 12 scientific or engineering jobs portrayed in Bollywood films, 91.7 per cent where held by men. Globally, the report said, girls and women are twice as likely as boys and men to be shown in sexually revealing clothing, partially or fully naked, thin, and five times as likely to be referenced as attractive.

In India there were more than six men working in the film industry to every one woman. This was, however, a better ratio than in France, Russia and Japan.

Kharana’s campaign to overturn the ban on women makeup artists has received widespread support. “If a person, male or female, has the right talent then he or she should be allowed to work and earn here,” said Subhash Shinde, a leading male makeup artist in Bollywood.

But Sharad Shelar, president of the makeup artist section of the Cine Costume Make-up Artists and Hair Dressers Association, defended the ban. “It’s just one lady who has a problem with our union rules. We haven’t seen any such protest from anyone else,” he said. “We are not against anyone, we want all of us to survive and work here. We have females working in Bollywood since last 55 years, as hair stylists. Why let any single person do all the jobs and affect other workers?”