Sydney: Children held in youth detention in Australia’s north had force used against them and were often kept in isolation, prompting feelings of being “a caged animal”, an inquiry heard Tuesday.

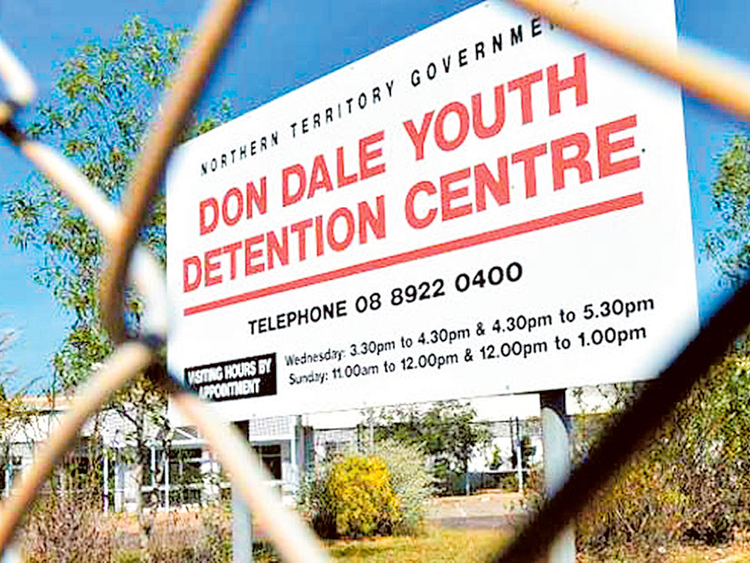

The government ordered the inquiry into the detention of children in the Northern Territory after video emerged of mostly indigenous boys being tear-gassed and mistreated at the Don Dale detention centre in 2014 and 2015.

At the inquiry’s first hearing on Tuesday, national children’s commissioner Megan Mitchell said she had visited the Darwin facility earlier this year and found it “old and ageing”.

“It was clear that use of isolation was routinely and frequently used and for very long periods of time — and when I say frequently and routinely I mean 23 hours a day for several weeks,” she said, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reported.

“It was also clear that the use of force was routinely used as part of the everyday business of the facility, not just when there was an incident. I think all of those things are breaches of children’s rights.

“When I asked the young people about how they felt in that environment, some of the words they said were depressed, angry, sad and like a caged animal.”

The inquiry was called in July after national broadcaster ABC showed graphic footage of teenagers being tear-gassed, stripped naked and roughly restrained at the centre in Darwin.

In one video from 2015, a 17-year-old boy is hooded, shackled to a restraint chair and left alone for two hours, prompting comparisons to Guantanamo Bay, the US military prison in Cuba for terror suspects.

While the commission is not focusing specifically on indigenous offenders, they are over-represented in the Northern Territory’s juvenile justice system, reportedly accounting for 95 per cent of children in detention.

Counsel assisting the royal commission Peter Callaghan said there had been dozens of inquiries into indigenous issues in the past, and questioned whether this showed an “inquiry mentality” which favoured reports over results.

“Do we need to confront some sort of inquiry mentality in which investigation is allowed as a substitution for action?” he said in his opening address, the ABC reported.

The royal commission, co-chaired by Aboriginal leader Mick Gooda, is due to report in early 2017.