Politics chases sporting achievement like a breathless autograph-hunter. In the past fortnight, I have seen Team Great Britain’s Olympic success deployed to buttress the case for central planning, public spending, market capitalism, Scotland staying in the union, European solidarity, Brexit, Yorkshirian exceptionalism, John Major, open borders, comprehensive education and, in one self-parodying Twitter excursion by a Tory MP, empire.

It makes sense to study the policy implications of a medal-winning system that works, but politics is drawn to sporting heroism by a less analytical appetite. It is the fervour of the crowd, the uncomplicated allegiance, the sense of shared national endeavour that unifies in victory and consoles in defeat — things that do not characterise competition for elected office. Who can blame the drought-stricken harvesters of reluctant votes for wanting to irrigate their parched soil with arguments drawn from the reservoir of Olympian goodwill?

It never works, because an essential quality of sporting spectacle is respite from the things that politics demands we think about. No one wants to ponder funding models while Laura Trott is whizzing around the velodrome on course for gold. When George Osborne turned up at the Paralympics in 2012, he was jeered for the offence of reminding people that there existed a realm where Osborne mattered. Intrinsic to the pleasure of waking up each morning to good news from Rio was the relief it provided from the preceding weeks of inescapable confrontation with events of darker gravity — the referendum on European Union (EU) membership and its consequences. A driver of the Tories’ surge in opinion polls since Prime Minister Theresa May entered Downing Street is surely an expectation that politics will become boring again in her hands. A new cycle of turbulence will disturb the peace, but for now, the prime minister elicits that most undervalued of public reactions to a leader: Comfortable indifference.

For the minority who do follow the minutiae, it is easy to confuse casualness of attention with ignorance. Anyone who has tried to extract political opinions from strangers — a niche pursuit of canvassing activists andvox-popping journalists — knows that the obligation to take a definitive view is often felt as a burden. This is not always an expression of alienation or contempt for politicians, although those are growing trends. I have observed focus groups of swing voters, selected for their record of conscientious participation in elections, and been struck by a combination of haziness on detail and acuity in extracting the essence of a situation. They often discern the outline of the wood better than those of us who spend our lives scrutinising bark on the trees.

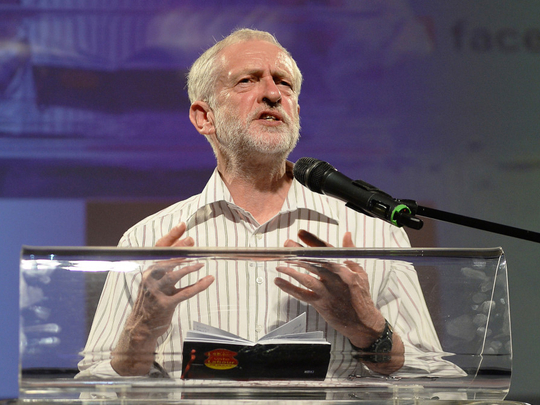

People who could not name a single member of former prime minister David Cameron’s cabinet knew instinctively that he had blundered complacently into a European referendum and would be undone by it. Former Labour supporters who dismiss Jeremy Corbyn laugh at the prospect of his becoming prime minister not because they love austerity but because he radiates pious amateurishness. These voters would, I suspect, be indifferent to the empty gesture of a Labour leader sitting on a train floor in ostentatious solidarity with miserable commuters, yet seize on the suspicion that he ignored vacant seats to stage the scene.

There is a wide spectrum of engagement between apathy and obsession. It is valid to care about Labour’s future and still rather spend a summer evening grappling with the arcane points system of omnium cycling than attend a leadership hustings. For the minority who do follow the minutiae it is easy to confuse casualness of attention with ignorance. There is the seductive distinction between those who get it and those who don’t: Dumb herd and wise shepherds. That fallacy is not unique to the Left, but more common there. Partly it is the residue of a Marxist conviction that politics follows quasi-scientific laws governing the distribution of economic power. If wealth is not justly apportioned across society, a majority will eventually demand redistribution. If they fail to rally to the Left’s manifesto, it must be because sabotage interferes with the signal.

Treasonous MPs suffocate the argument; corporate interests use rotten media to fill the empty vessel of public consciousness with false belief. It is true that British press coverage is skewed against liberal arguments on immigration and social-democratic prescriptions for economic restructuring. It is also true that no workable strategy for overcoming that bias involves retreat into self-righteous resentment of anyone who questions the viability of a radical left project.

There is a tendency in Labour, predating Corbyn’s leadership but massively amplified by it, to map politics on an axis from stupidity to enlightenment with parallel lines on the graph showing a journey from right to left and indifference to enthusiasm. It follows that an increase in the exuberance of support for a retro-socialist candidate indicates real progress. But when you consider that most people see political fandom as a mark of eccentricity, a noisier fan club is more likely to indicate higher barriers separating the party from the rest of the country. To pack a venue with hundreds of people chanting in unison, declaring their allegiance on T-shirts, is an achievement matched by non-league football clubs that never win trophies and bands that never top the charts. It is politics as a serious hobby, leaving serious politics to the professionals.

The Tories understand this. While conservatism has ideological components, it succeeds when those strains are couched in tones of managerial moderation — the promise to mind the shop, freeing up voters to pursue their lives unencumbered by a duty to be overtly political. A historic failure of Labour has been the inability to challenge an unspoken cultural presumption — internalised even by many of the party’s supporters — that Tory rule is Britain’s default setting, interrupted only by episodes of left-ward correction. Former prime minister Tony Blair unsettled that view, then his party disowned the achievement. May is now the happy beneficiary of a return to the traditional roles: Tories govern; Labour complains. Labour offers politics as a febrile state of mind; the Tories handle politics for people who would rather be doing something else.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Rafael Behr is a political columnist for the Guardian. He has been political editor of the New Statesman, chief leader writer on the Observer and a foreign correspondent for the Financial Times in Russia and eastern Europe. He was named Political Commentator of the Year in the 2014 Editorial Intelligence comment awards.