In 2015, just as refugees were pouring out of Syria and pictures of terrified children filled every newscast and front page in the world, a small notice appeared in my church bulletin: “Are you looking for a way to help our city’s newest refugees?” It was a call for volunteers to assist in an English-language classroom at a local public school. I was once a high school literature teacher, so I saved it, planning to follow through whenever life slowed down a little. More than a year later, I was still dithering. The day after Donald Trump was elected, I finally volunteered.

The sun was just rising when I left for my first class. I’d been away from school for 20 years, and I was a little nervous, but when I walked through those doors I felt instantly at home. In the school office three mirrors hang side by side, each marked by the kind of inspirational message schools specialise in: “College Ready.” “Career Ready.” “Life Ready.” While I signed the visitors’ log, two students wearing hijabs hugged each other goodbye in the bright corridor, and the principal switched on the intercom to lead the Pledge of Allegiance.

Teachers at this school face all the challenges of any teacher in a building full of teenagers, but in the Trump era their job is incalculably harder. My oldest son is a middle-school teacher at another Nashville school with a large immigrant population. On November 9, his students arrived in class shaken, aware of what the new administration would mean for their families. Already a man had thrown a can from his car window at the older sister of one student, yelling “Terrorist!” as he passed.

“Build that wall! Build that wall!” The chants at Trump rallies are chilling, vicious, the voice of a mob, but among the many conservatives I know — those who voted for Trump and those who didn’t — there is not a single person who would throw a can at a child or assume that a Middle Eastern-born teenager must be a terrorist. They welcome immigrants who are here legally, but they argue for a level playing field, where newcomers are bound by the same rules they are bound by themselves. So Tennessee’s official attitude toward immigrants is what you’d expect from the conservative South: It joined 15 other states in signing an amicus brief supporting Trump’s travel ban.

Nashville has one of the fastest-growing immigrant populations in the country. Close to 12 per cent of the city’s residents are foreign-born, and 30 per cent of public-school students speak a language other than English at home.

Palpable uneasiness

The city has made a point of welcoming international newcomers, despite the actions of the Tennessee General Assembly, which meets in the heart of downtown. Metro schools don’t inquire about immigration status; instead, they offer mentors to foreign-born families. Workers at the city’s public libraries help newcomers apply for citizenship. Metro police officers don’t check the immigration status of people pulled over for traffic violations. The uneasiness here is palpable anyway. Seventy per cent of Nashville residents support a path to citizenship for unauthorised immigrants, but such numbers offer little reassurance when Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents posed as Metro police officers during a recent roundup of Nashville Kurds.

The challenge of teaching “English learners,” as they are called in Metro schools, is immense, and this political climate only adds to the complexity of the task. The students in an English learners classroom speak many different languages at home, and their English-language competence varies widely. Every single step in the process of speaking — or listening, or reading, or writing — must be broken down and explained. To borrow a line from Joan Didion, English is a language I play by ear, and volunteering in this classroom has taught me more about my native tongue than graduate school did.

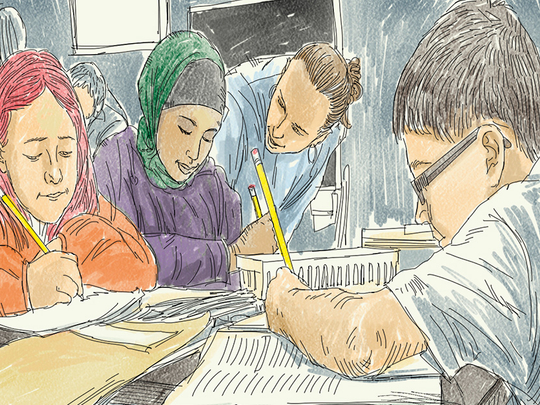

A typical class includes a lesson followed by a chance to work in pairs, taking turns reading (or speaking) and listening (or writing). As the students work, the teacher moves from table to table, and my job is to do the same, answering questions or serving as a partner for a student without one. At times I’m flummoxed by a student’s question, and then all the other kids at the table pitch in to explain. They don’t speak one another’s languages, either, but they understand better than I do what’s puzzling about the lesson, and they help one another — and sometimes me — understand.

Talking with these teenagers, I’m always struck by how familiar they seem. There’s the class clown, raising his hand to ask a silly question that makes his classmates laugh. There’s the school beauty, who never leaves her seat — she knows the others, vying to be her partner, will come to her if she waits. There’s the sleepy kid trying to nap undetected behind an open book, and the Type A kid with a hand always in the air. Their clothes and hairstyles are different, but they seem exactly like the suburban students I once taught; exactly like my own three sons, the youngest still a teenager himself; exactly like my high school classmates.

Only they aren’t exactly alike. Because they live in a nation with an incoherent and punitive immigration policy, these students — new residents of a growing, multicultural city — are as vulnerable as any immigrants in the red-state countryside. They live with the inescapable fear of deportation, their own or a loved one’s, and yet they come to class every day to master the language and culture of their difficult new home. In this effort, teachers are their staunchest allies.

In the EL classroom, there’s more to learn than language. During a unit on the Harlem Renaissance, I arrived to find a newly decorated bulletin board fashioned from an assignment modelled on Countee Cullen’s ‘Heritage’. The poem begins, “What is Africa to me?”

The students’ own poems were titled “What Is Myanmar to Me?” (“Spicy foods, we’ll take seconds, please”), and “What Is Zambia to Me?” (“I can feel the hot weather in my body/A beautiful sun outside on my face”), and “What is Mexico to Me?” (“I’m like a flame,/Waiting to go back again”) — on and on and on. I stood before that bulletin board with my back turned to hide my tears, and I read every poem.

School’s out for summer now, but I can’t stop thinking about all those brand-new Americans recalling the countries of their birth, using the poetry of their new language to convey the beauty of home. English is a problematic language, but these students are working hard to learn it — and working harder still to belong.

— New York Times News Service

Margaret Renkl is a contributing opinion writer.