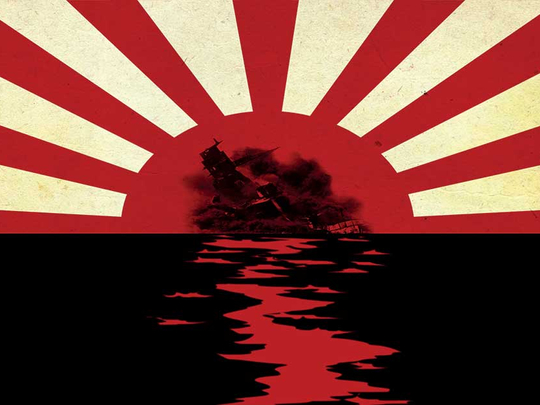

Few events in the Second World War were as defining as the Japanese assault on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The “date which shall live in infamy” — as former United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt had famously put it — prompted the American entry into the War, subdued an entrenched isolationist faction in the country’s politics, and, in the long run, prefigured Washington’s assumption of the role of global a superpower.

A total of 2,403 Americans died and 19 vessels were either sunk or badly damaged in the attack, which involved more than 350 warplanes launched from Japanese carriers that had secretly made their way to a remote expanse of the North Pacific. It caught the brass in Hawaii by surprise and stunned the nation.

“With astounding success,” Time magazine wrote, “the little man has clipped the big fellow.”

But the big fellow would hit back. Japan’s bold strike is now largely seen as an act of “strategic imbecility”, a move born out of militarist, ideological fervour that provoked a ruinous war that Japan could never win and ended in mushroom clouds and hideous death and destruction at home.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the Japanese naval commander, hoped his plan to attack Pearl Harbor would deliver a fatal blow to American capabilities in the Pacific and convince Washington to push for a political settlement. Otherwise, he knew that his country stood no chance against the US in a protracted war, according to Steve Twomey, author of a new book on the tense build-up to Pearl Harbor.

Twomey documents Yamamoto’s initial opposition to engaging the US: “In a drawn-out conflict, ‘Japan’s resources will be depleted, battleships and weaponry will be damaged, replenishing materials will be impossible,’ Yamamoto wrote on September 29 to the chief of the Naval General Staff. ‘Japan will wind up impoverished,’ and any war ‘with so little chance of success should not be fought’.”

But with war a fait accompli, Yamamoto conceived of a raid that would be so stunning that American morale would go “down to such an extent that it cannot be recovered,” as he put it. Unfortunately for him, the US was galvanised by the assault — and had its fleet of aircraft carriers largely unscathed. A plane carrying the Japanese admiral would be shot down over the Solomon Islands by American forces in 1943 with the US counter-offensive already well under way.

Could it have gone differently? No modern conflict has spawned more alternative histories than the Second World War. In the decades since, writers, Hollywood execs and amateur historians have indulged in all sorts of speculation: What the world would look like if the Axis powers triumphed, or if the Nazis crushed the Soviets, or if the US had not deployed nuclear weapons or if Roosevelt had chosen not to enter the war at all.

But even if Japan had not attacked Pearl Harbor, it’s quite likely that the two sides would have still clashed.

For imperial Japan, the US posed a fundamental obstacle to its expanding position in the Pacific. Here was a resource-hungry island-nation eager to assert itself on the world stage in the same way European powers had done in centuries prior. By the summer of 1941, it had seized a considerable swath of East Asia, from Manchuria and Korea to the north to the formerly French territories of Indochina further south, and was embroiled in a bitter war in China.

American sanctions attempted to rein in Tokyo: Washington slapped on embargoes on oil and other goods essential to Japan’s war machine. The price to have them lifted — a Japanese withdrawal from China, as well as the abandonment of its “tripartite” alliance with Germany and Italy — proved too steep and humiliating. So Japan calculated further expansion in order to access the resources it needed.

“Our increasing economic pressure on Japan, plus the militaristic cast of the government ... and their partial loss of face in China, spelled a probable resumption of their policy of conquest,” mused a lengthy essay in the Atlantic, published in 1948. “In what direction would the Japanese strike, and against whom?”

Japan opted not to venture into Soviet Siberia. In 1939, Japanese troops had suffered a chastening defeat at the hands of a combined Soviet and Mongolian army and its forces were already bogged down on various fronts in China.

The decision was made to target the vulnerable British and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia — what’s now the independent nations of Myanmar (then Burma), Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia. The Japanese knew this would likely spur a greater response from the US, which then controlled the Philippines and other scattered island possessions in the Pacific.

“Unwilling to give up what it wanted — a greater empire — in return for the restoration of lost trade, unwilling to endure the humiliation of swift withdrawal from China, as the Americans wanted, Japan was going to seize the tin, nickel, rubber and especially oil of the British and Dutch colonies,” wrote Twomey.

The rest is history.

Some observers, though, reckon that American policy could have forced imperialist Japan’s hand.

“Never inflict upon another major military power a policy that would cause you yourself to go to war unless you are fully prepared to engage that power militarily,” wrote American historian Roland Worth Jr., in No Choice But War: The United States Embargo against Japan and the Eruption of War in the Pacific. “And don’t be surprised that if they do decide to retaliate, that they seek out a time and a place that inflicts maximum harm and humiliation upon your cause.”

Roosevelt’s battle with the isolationists

Meanwhile, in the US, president Roosevelt faced widespread public opposition to entering the war. The memory of the First World War — a struggle many Americans believed wasn’t worth fighting — still loomed large in the political imagination. Roosevelt faced off a 1940 election challenge by pandering to anti-war voters. “I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again and again,” he declared on the campaign trail in Boston in October 1940. “Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.”

But Roosevelt was steadily trying to engage in the conflicts abroad, no matter his rhetoric. He was an avowed anti-fascist and was preoccupied more by Nazi aggression in Europe than Japanese inroads in Asia. His political opponents fretted that he would push towards a greater confrontation. This included figures from the America First movement, a big tent coalition of isolationists, nationalists, pacifists and, indeed, some anti-Semites, who wanted the US to cling to a policy of neutrality and weren’t that bothered by an ascendant fascism in Europe.

Charles Lindbergh, the legendary aviator, was one of the more prominent champions of the America First cause.

“The pall of the war seems to hang over us today. More and more people are simply giving in to it. Many say we are as good as in already. The attitude of the country seems to waver back and forth,” Lindbergh wrote in his diary on January 6, 1941. “Our greatest hope lies in the fact [that] 85 per cent of the people in the United States (according to the latest polls) are against intervention.”

In March 1941, Roosevelt convinced Congress to pass the Lend-Lease Act, which “loaned” arms and ships to the beleaguered Allies in Europe. US warships engaged Nazi submarines in the Atlantic and protected convoys bearing relief supplies to the British. Months of secret diplomacy with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill already bound Roosevelt’s administration to the Allied cause, but the US was not yet formally in war.

The attack on Pearl Harbor in December gave Roosevelt all the ammunition he needed. Germany, in alliance with Japan, declared war on the US four days later, saving Roosevelt the trouble of having to do it himself.

The isolationists were defeated. “I can see nothing to do under these circumstances except to fight. If I had been in Congress, I certainly would have voted for a declaration of war,” Lindbergh lamented. Other politicians in Congress, mostly Republicans, would soon lose elections and become an irrelevant wing of the party.

Without the American entry into the Second World War, it’s possible that Japan would have consolidated its position of supremacy in East Asia and that the war in Europe could have dragged on for far longer than it did. America’s role in the war forced Nazi Germany to commit a sizeable troop presence in Western Europe that it would have otherwise diverted to the withering invasion of the Soviet Union. It helped turn the tide of battle.

For decades since, though, conspiracy theories have surrounded Roosevelt’s role in the build-up to Pearl Harbor, with a coterie of revisionist historians alleging he deliberately bungled military coordination and obscured intelligence in order to provoke the crisis that led to war. Most mainstream historians dismiss these claims.

“He was totally caught off guard by it,” Roosevelt biographer Jean Edward Smith told the National Public Radio last week. “The record is clear. There was no evidence of the Japanese moving towards Pearl Harbor that was picked up in Washington.”

— Washington Post

Ishaan Tharoor writes about foreign affairs for the Washington Post. He previously was a senior editor at Time.