United Kingdom Prime Minister Theresa May and her pro-hard Brexit Conservatives made significant gains in Thursday’s local elections across Britain. The party won more than 550 council seats and swept to victories in mayoral contests in the West Midlands and the Tees Valley.

Behind the raw results of the local elections, however, a potentially even more important back story is playing out that could have key consequences for UK politics. That is, Brexit is driving new positioning by some of the nation’s main parties — those with representation in England, Scotland and Wales — which could, ultimately, produce significant, new anti and pro-European Union (EU) cleavages in the electorate, potentially realigning the political map.

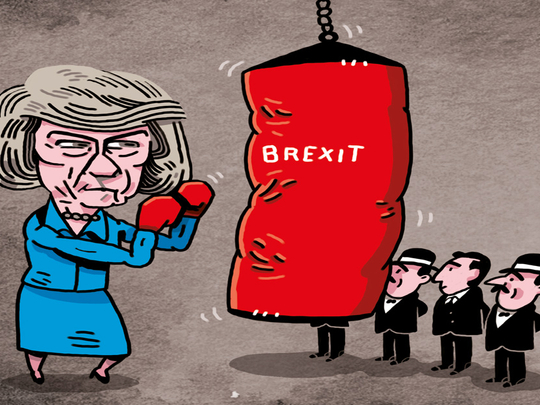

The main beneficiaries — so far — of this emerging development have been the Conservatives who are unifying around the government’s Brexit stance. Like May herself, this includes many former Remainers who have now switched sides to back her vision for a hard exit from the EU.

The major shift in positioning by the Tories on the EU has injured, perhaps fatally, the United Kingdom Independence Party (Ukip) whose vote collapsed on Thursday. The Ukip lost every council seat it was defending.

At the other end of the Brexit spectrum, the Liberal Democrats are seeking to make political capital through steadfast opposition to the government’s hard EU exit stance. While this has given the party clearer differentiation, there was no strong sign on Thursday of an electoral surge, with the Liberal Democrats actually losing council seats overall.

Thursday’s results served as the warm-up act for the June 8 snap general election, with Brexit potentially the dominant issue. The chief reason the prime minister asserted for calling this unexpected vote, which was previously scheduled for 2020, is that opposition parties are, by and large, at odds with her Brexit plans.

She told the country that she is not prepared to allow, in her own assessment, her political opponents to jeopardise the forthcoming exit negotiations with the EU. She claimed the “country is coming together [on Brexit], but Westminster is not” and what the country needs is “certainty, stability and strong leadership”.

Yet, despite the strong showing of Conservatives on Thursday, this characterisation by May is too simplistic. Contrary to her assertion, there is, in fact, important disagreements across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland about Brexit, including what the meaning and implications are of last June’s EU referendum.

The prime minister has made clear her strong view that immigration and sovereignty were the primary drivers behind the Leave campaign’s victory last Summer. From this perspective, it follows that controlling migration flows from the EU and ending the jurisdiction in the UK of the European Court of Justice should become the key UK objectives for the forthcoming Brexit negotiations.

Given the EU’s commitment to the free movement of goods, people, services and capital, this has pushed May towards her hard Brexit negotiating stance, which opposition parties have expressed significant concerns about. This hard Brexit will see the UK, in May’s words, discarding all “bits of the EU”, including membership of the 500-million consumer European Single Market, full membership of the EU Customs Union, leaving the Common Commercial Policy, and no longer being tied to the Common Commercial Tariff.

However, May’s narrative about Brexit is far from the entire picture, and there were — in fact — diverse and sometimes divergent views expressed by people voting to exit the EU last year. Some Leave voters, for instance, including isolationists, focused last June on perceived costs and constraints of EU membership other than immigration and sovereignty, including the issue of UK financial contributions to the supranational organisation’s budget.

Many voters in Britain were encouraged by the claim made in the referendum that leaving the EU would mean a mammoth £350 million (Dh1.66 billion) a week financial bonanza that could be ploughed back into the National Health Service. However, this misleading pledge has since been dropped by Brexiteers.

Others voted to Leave the EU for a vision of a buccaneering global UK that could, post-Brexit, allow the nation to secure new ties with non-EU countries, including in Asia-Pacific, the Middle East and the Americas. Meanwhile, a significant slice of the electorate voted Leave as a protest against non-EU issues such as the domestic austerity measures implemented by UK governments since the 2008-2009 global financial crisis.

Contrary to what May now insists, the Leave vote, therefore, encapsulated a range of sentiments, and there was (and still is) not an overwhelming consensus across the nation behind any specific version of Brexit, whether hard or soft, disorderly or orderly. The continuing divisions within the electorate on these issues are underlined in polls that tend to show the country split over whether maintaining access to the European Single Market or being able to limit migration should be the key objective in negotiations.

These are the key questions that May therefore wants to try to see resolved in next month’s general election in which she is seeking her first mandate from the country as Conservative party leader. She will argue — should she win a vastly bigger majority in the House of Commons — that she has the backing of the country behind her hard Brexit stance.

May’s decision to call an election is thus based on her belief that she can win a huge, historic victory on June 8. This is by no means certain, however, and the sizeable polling lead of Conservatives could yet soften if opposition parties turn in a strong performance and present an attractive, alternative ‘Brexit and beyond’ vision for the UK that energises voters across the nation.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.