Political power has an alluring sense of permanence. Once in the driving seat, politicians tend to want to stay there. It happens in democratic systems, in republics and certainly happens in totalitarian regimes. Just look at Russian President Vladimir Putin or Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. They are just among the many who want to keep thrashing the political horse.

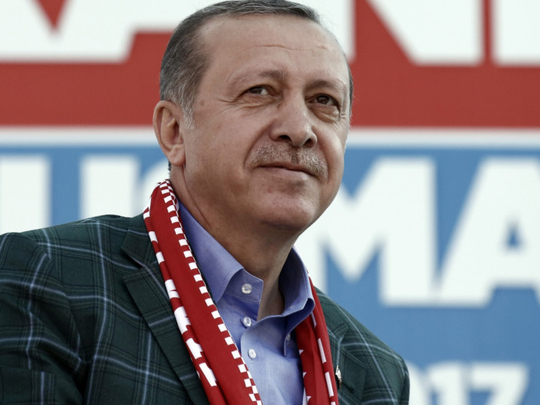

And so it appears to be the case for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a long-time Islamic politician who has been on top of the political pyramid in Turkey for at least 14 years, certainly longer than Mustapha Kamal Ataturk, who established the modern Turkish republic in 1923.

With Erdogan, the cycle of political power never seems to be bottoming-out. His country just voted on a constitutional referendum that will see him continue as Turkey’s president until at least 2029 and possibly 2034. From now on, Turkey will likely get a belly-full of the debonair and illustrious president under a perfectly applied “democratic” republican political system, where his appeal and power-base is increased under the coinage of “populism” that brought US President Donald Trump into the White House.

Erdogan is a determined politician, with a sense of style and panache and popular appeal regardless of the secularism of Turkey. With a pulse on the Turkish street, he has didactic attributes that stretch from being charismatic, a newfangled Islamist, being pugnacious and ubiquitous with an omnipresent personality cult.

Regardless of the derogatory adjectives that are thrown at him — he has a big heart — the constitutional reforms he introduced through the latest referendum — and regardless of the slim voting percentage differences — Erdogan managed to “transform” the country in one scoop from a parliamentary democracy to a presidential system based on the United States and French models, although his critics would certainly disagree with that.

Far-reaching changes

The Turkish constitutional changes— 18 amendments in total, which are likely to take effect in 2019 when the country holds its first presidential election — are far-reaching in that they scrap the post of prime minister and concentrate power in Erdogan’s own hands. Erdogan will now make policy, issue decrees, control the public budget and appoint judges, ministers, vice-presidents and high state officials, with all powers concentrated around him.

This has already been happening since 2014, when he became president. The previous constitution required him to relinquish his post as head of the ruling Justice and Development Party, which had formed successive governments following since 2003. However, under the new amendments, Erdogan, as president, will now be able to preside over his own party in the Turkish legislature, thus creating a link between the presidential seat and parliament and adding further to the consolidation of his power.

This now becomes a formality as it is argued Erdogan already controlled the government since 2014 because of his links to the AKP. Still, the amendments certainly give him more political clout across the Turkish political system. For Erdogan, the constitutional changes mean more stability and governance to institute growth — a reminder of an earlier era beginning in 2003 when the economy was buoyant and people enjoyed the fruits of his expansionist policies.

He argues passionately that the new constitutional changes will improve the security situation in the country. This can be taken as a code word for his efforts to ensure that any tempted coup against him, similar to the one in July 2016, will never take place again as he will be in a position to keep tabs on an army whose presence is well-known in Turkish politics.

Erdogan’s dexterity and astuteness in handling the coup attempt and making sure it did not succeed are all part of the Turkish president’s role. He has maintained his appeal with voters through Facebook, Twitter and other social media and it was through this that the Turkish people were able to thwart the coup at the last minute. It was the same Turkish people who most definitely voted ‘yes’ to the constitutional amendments, thus maintaining Erdogan’s populism, despite the dreariness surrounding the fact that crucial cities like Istanbul, of which Erdogan was mayor in the 1990s, as well as Ankara and Izmir voted against him, thus eating into his once-thriving middle class base. Could these reflect a long-term change? It is definitely a change of the times, a new constitutional reference to a Turkish presidency that seeks to be more robust, forthright, more traditional and authoritarian and which Erdogan is constantly being accused of.

Strains of present times

However, one thing is clear: What has happened also is a sign of the strains of the present times, meaning that the president must act quickly to alter course — something which he promises to do. It would be an understatement to say that many at a local and international level are worried about the new developments. One of the pitches for supporting a “strong” presidency was that it allowed him to take decisions quickly and deal with the increasingly dangerous situation on his doorstep in Syria or the rise of Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Syria and Iraq), or so it is argued. Another of course was that a strong presidency would allow him to stand up to Russia, and possibly Iran, thus flexing more Turkish muscle in the region.

All this is water off a duck’s back, critics argue. They see that what is at stake is democracy in Turkey and the muzzling of parliament. There will no longer be any checks and balances, as the lines of the separation of powers have become blurred. Alarmists argue this is the death of democracy, and though they could be over-playing the issue, the new amendments mean Erdogan will no longer be questioned directly by the people’s representatives. Only his subordinates will have that ‘privilege’ but even then, questions must be written down.

Of course it is too early to tell how things will really develop. However, one thing that’s certain is that Erdogan has made a political gamble and has won, no matter how high or how low the electoral stakes registered. His appeal at the end of the day may act as a check to his ‘sultanic’ powers that he will definitely accumulate come 2019 because whatever he is, Erdogan won’t in the end go for an all-out divisive stand and alienate Turkish society and its political system because of his stake in both.

Marwan Asmar is a commentator based in Amman. He has long worked in journalism and has a PhD in Political Science from Leeds University in the UK.