During a discussion about the Iran nuclear deal, Rex Tillerson, US President-elect Donald Trump’s pick for Secretary of State, wrongly asserted that it prevents Iran from building a bomb but allows it to buy one.

He later corrected that statement, but the fact that he made it at all demonstrates both a shocking lack of understanding of an important international agreement and a worrying dependence on talking points that appear to have been written by ideologues rather than professionals.

For all the disquiet Iran causes around the region, it is important that the United States approach it calmly and professionally. A nuanced understanding of Tehran’s myriad political players and how action on one front (the nuclear deal, for example) may affect Iran’s conduct in other areas (relations with the Gulf, or the war in Syria, to name only the two most obvious things) is essential as we enter a potentially tumultuous period.

The next six months are a particularly dangerous and uncertain time. Most immediately, a new US president takes office this week. One who has no experience in government and whose views on nearly everything often seem to be driven by a combination of ego, emotion and a canny sense of whatever his audience of the moment wants to hear.

Political season in Iran

In Iran, the political season is heating up. A presidential election will be held in May and as opaque as the Iranian political system can be, it is clear that the nuclear deal and the economic progress that President Hassan Rouhani promised would follow in its wake are likely to be central issues in the campaign.

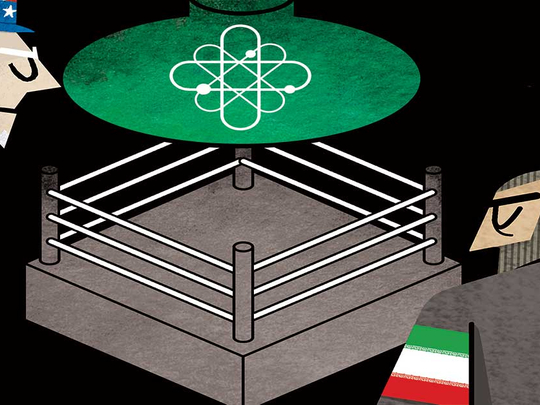

Meanwhile, the loudest voices in the US these days are not debating the merits of the accord, but rather whether the best plan is to impose new sanctions on Iran or simply to tear up the nuclear deal. This is a strategy nearly certain to enhance the standing of Rouhani’s hardline opponents and their argument that efforts to end Iran’s international isolation were a mistake from the beginning.

The result is a dangerous moment in which hardliners on both sides may well seize control of the debate. Beyond the ill-briefed Tillerson, the main people advising Trump on Middle East policy are going to be his son-in-law Jared Kushner, his conspiracy-mongering National Security Adviser Michael Flynn and Flynn’s deputy, K.T. McFarland, whose experience consists mainly of being an ideological talking head on Fox News.

James Mattis, the level-headed former general who is Trump’s pick for Secretary of Defence, has come out against blowing up the nuclear deal, despite having expressed scepticism about it when it was first sealed. So have a number of establishment foreign policy figures who initially opposed the accord. Whether their views carry the day, only time will tell.

In the typical way of American pundits and politicians, everyone around Trump seems to pay little heed to what America’s allies in Europe and the Gulf might think about such an abrupt change in policy; how it might effect broader relations with Russia and China (which are both also signatories to the nuclear deal) and, perhaps most importantly, the fact that the Iranians might have something to say about all this.

Two-way street

Washington often forgets that the question is not only whether the US is willing to talk to the Iranians. Whether the Iranians want to talk to Washington is also part of the equation. The primary argument Iranian hardliners make against Rouhani is that he oversold the nuclear agreement’s economic benefits and is too ready to compromise with the West.

If Trump’s team wind up validating that view, they may find themselves confronted with a new Iranian administration, one that prioritises conflict over diplomacy.

I do not want to seem naive about Iran. Its politics are complex and unusually difficult for outsiders to follow. Its president’s authority is circumscribed by other powerful institutions such as the Revolutionary Guards and the Supreme Leader.

It is also true that the nuclear deal has never been particularly popular in the Arab world and that nothing in it addresses Iran’s behaviour elsewhere in the region.

If one believes that Rouhani really does little more than provide cover for Iran’s hardliners, there could be a certain comfort in seeing confrontation once again become the country’s avowed policy toward the rest of the world. But with so much other uncertainty surrounding both the Middle East and the new American administration, that approach is exceptionally shortsighted.

For eight years Barack Obama believed he had a mandate to de-escalate regional tensions and keep America out of new Middle Eastern wars. For all the criticism his policies generated both at home and abroad, we may all look back on them wistfully if the coming year sees newly empowered ideologues in both Washington and Tehran driving their countries toward a direct confrontation.

— Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches political science at the University of Vermont