How did Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the world’s favourite liberal mascot — a feminist man, with movie-star good looks, a 50 per cent female Cabinet and a political lexicon that has replaced “mankind” with “peoplekind” (making millions swoon) — end up looking silly, diminished and desperate on his trip to India last week?

Trudeau’s eight-day India expedition has been an absolute fiasco.

Hours before meeting Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, his journey hit a dead end when the Canadian high commissioner invited a Sikh extremist named Jaspal Atwal (who has been convicted of attempted murder and was previously affiliated with a terrorist group) to a dinner to honour Trudeau in New Delhi. Atwal was found guilty of trying to kill an Indian minister in 1986. He was also blamed for an assault on Ujjal Dosanjh, the former premier of British Columbia.

By the time Atwal’s invitation was rescinded — Trudeau called it “unfortunate” — Atwal had already posed for photographs with Trudeau’s wife, Sophie, in Mumbai, as well as with other members of his entourage.

“It’s a disaster,” Vishnu Prakash, former Indian high commissioner to Canada, told me. “I am convinced Trudeau was blindsided. Whoever drew up the list screwed up and dealt him a fait accompli. But it is also symbolic of how Khalistanis have penetrated the system.”

Since Trudeau won the election in 2015, the 1980s have returned to haunt Indo-Canada ties. Sikh secessionists who supported a separate country (Khalistan) unleashed a bloodbath in the state of Punjab in the 1980s. Indira Gandhi, the then Indian prime minister, sent the army to purge the Golden Temple (the holiest place of worship for Sikhs) of militants who were hiding inside. She was assassinated by her own Sikh bodyguards, followed by anti-Sikh riots in which more than 3,000 were killed. In 1985, the Air India jumbo jet ‘Kanishka’, flying from Montreal to New Delhi, was blown up mid-air by Sikh terrorists, leaving 329 people dead.

Knowing all of this, Trudeau still attended a Khalsa parade in May, where many militants were feted. So, his India trip was already mired in tensions when the Atwal fiasco broke. Then, Canadian media released more photographs showing an apparent familiarity between Atwal and Trudeau back home. Nearly half a million Sikhs live in Canada and account for 1.4 per cent of the population. Trudeau was such a favourite among them that he is jokingly called Justin Singh. Now he has competition. Jagmeet Singh, who recently took over the reins of Canada’s New Democratic Party, is considered left of Trudeau’s left. He even refused to condemn the terrorist who blew up the Air India plane.

“Trudeau’s India trip from the outset was playing to a diaspora gallery back home, one in which he has been studiously ambiguous on the Khalistani ties of some of his Liberal Party’s Sikh Canadian supporters,” Vivek Dehejia, a professor at Carleton University in Ottawa told me. “But for those who are lukewarm on Trudeau, this will reconfirm their impression that the rock-star image hides feet of clay, and that he has been undone by his own cleverness in trying to massage the diaspora vote back home [and] yet appear statesman-like in India. That facade has crumbled.”

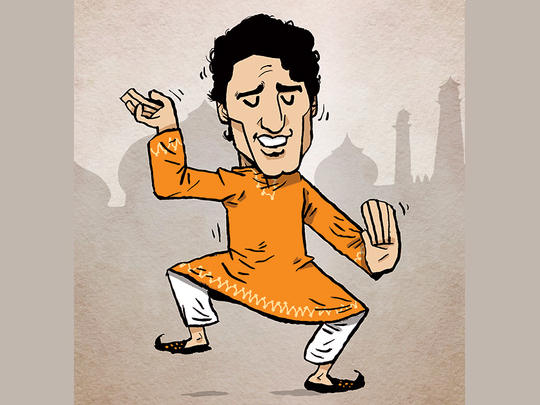

Given the seriousness and the sensitivities at stake, it was infuriating to watch Trudeau sashaying out, doing the Bhangra dance, at the same Canadian reception last week that was at the heart of the storm. You could feel the collective groan of Indians: Please. Stop. Enough Already.

I confess, from afar, I used to be a Trudeau fan-girl. But after this trip, I’ve changed my mind. Trudeau has come across as flighty and facetious. His orchestrated dance moves and multiple costume changes in heavily embroidered kurtas and sherwanis make him look more like an actor on a movie set or a guest at a wedding than a politician who is here to talk business. Suddenly, all that charisma and cuteness seem constructed, manufactured and, above all, not serious. “He seems more much more convinced of his own rock-star status than we ever were,” said one official in the Indian government who preferred to remain anonymous.

Indians are also wondering, what is Trudeau doing there for so long? Doesn’t he have a country to run?

The length of Trudeau’s stay may help explain why the trip started on a discordant note. Government sources tell me India urged Canada to cut the trip shorter or to at least sequence it differently. India wanted to start the trip with political talks before Trudeau played tourist. The Canadians disagreed. Also, the Canadians expected Modi to accompany Trudeau to his home state of Gujarat, just as he had done with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamain Netanyahu. But India declined.

“There was a disconnect between Canada’s expectations, which had very little basis, and what we were ready to do,” said Prakash, pointing out that 200 heads of state have visited India in four years. “Receiving leaders at the airport is an exception. And the Canadians should know — Modi has only gone to Gujarat with those leaders he has personally invited there.”

The frostiness with which Trudeau has been received is quite telling in a country where ‘Atithi Devo Bhavah’ - “the guest is equivalent to God” — is usually the philosophy towards hospitality. Modi finally met and hug the Trudeau on Friday, the sixth day of the Canadian premier’s India tour, and the only half-day of his sojourn that officially counted as “work”!

Most people agree that the Modi government has shown impressive toughness in setting the terms and in offering bipartisan support to the opposition leader, Captain Amarinder Singh, who is the Chief Minister of Sikh-dominated Indian state of Punjab. Singh had first accused Trudeau of backing Sikh separatists. Singh’s media adviser, Raveen Thukral, told me that Trudeau gave a “categorical assurance that his country did not support any separatist movement in India” and drew parallels with Quebec, saying that he “had dealt with such threats all his life and was fully aware of the dangers of violence”.

Sounds good. So next time you come to India, Prime Minister Trudeau, do try and leave the terrorists — and the wedding kurtas — at home.

— Washington Post

Barkha Dutt is an award-winning TV journalist and anchor with more than two decades of reporting experience. She is the author of This Unquiet Land: Stories from India’s Fault Lines. Dutt is based in New Delhi.