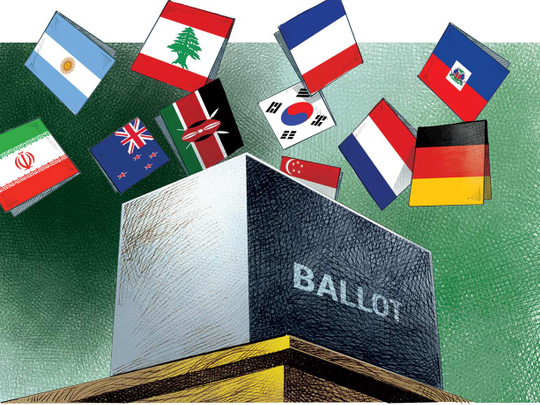

The eyes of much of the world are currently on the aftermath of November’s landmark US ballots, and the forthcoming inauguration on January 20 of President-elect Donald Trump as president. However, while 2016 was a big election year, there are also a wide range of eye-catching ballots in the next 12 months, across every continent. This will have very important ramifications for domestic politics, economics, and international relations for years to come.

In the Middle East, for instance, there is a key Iranian presidential election in May, plus a legislative ballot in Lebanon the same month. The poll in Iran will be watched across the globe as President Hassan Rouhani, should he definitely seek a second term, faces a potentially exceptionally tough battle against a resurgent conservative opposition which could be further energised if Trump decides to try to abandon the nuclear deal signed last year by Tehran, Washington, and several other powers.

Outside of the Middle East, there are key legislative ballots in Haiti (January) plus The Netherlands (March), and also presidential polls in France (April and May) which could see far-right National Front candidate Marine Le Pen, who has promised a referendum on the country’s membership of the EU, trying to run a Trump-style anti-establishment campaign to score an upset victory.

In the second half of the year, there are presidential and parliamentary elections in Kenya (August), a legislative ballot in Argentina in October, plus presidential elections in December in South Korea. Moreover, a presidential ballot is scheduled to take place in Singapore before August 26, and legislative elections must occur in Germany by October 22, and New Zealand by November 18.

The poll in Germany, where Chancellor Angela Merkel is expected to win power again, could be especially important for the EU. With Brussels and the continent at large facing another uncertain period, after a very difficult 2016 which saw the Brexit vote, her political experience and influence may well be needed to help the currently 28-member bloc navigate the challenges that coming years will bring.

While the precise outcome of these elections is uncertain, what is sure is that foreign political consultants will be working behind the scenes in many of these countries trying to steer candidates to success. It is estimated that US consultants, alone, have already worked in more than half of the countries in the world.

In 2017, that tally will only grow as firms, fresh from working on the US presidential and congressional elections in 2016, reach out to more uncharted international territory. Indeed, originating in the US, political campaigning has become a mini-industry driven by the potentially significant rewards on offer.

For instance, it is estimated by the US Centre for Responsive Politics that the overall cost of the 2016 US presidential and congressional elections was around some $6.6 billion (Dh24.2 billion). Of that massive sum, consultants earned a significant slice for their services, including polling, campaign strategy, telemarketing, digital advice, and producing advertisements.

While the success, internationally, of this army of consultants is mixed, the phenomenon has had a lasting impact, prompting what some have called the globalisation of politics. However, in the eyes of critics it is an international triumph of spin over substance that has tended to promote more homogenous campaigns with a repetitive, common political language.

As James Harding documents in Alpha Dogs, the origins of this phenomenon lie in the 1960s and 1970s. It was then that US political consultants began exporting US political technologies and tactics into Latin America and, then, ultimately across the globe.

A key underlying premise is that those technologies and tactics can achieve success just about anywhere. Thus, many foreign countries are sometimes deemed as mere international counterparts of US election battleground states such as Pennsylvania and Florida.

What started as international elections and campaigning work soon branched out into providing more foreign governments, leaders and bodies such as tourism and investment authorities with international communications advice and ultimately what is now known as ‘country branding’. Country branding is founded on the realisation that, in an overcrowded global information market place, countries and political leaders are, in effect, competing for the attention of investors, tourists, supranational organisations, non-government organisations, regulators, media and consumers.

In this ultra-competitive environment, reputation can be a prized asset (or potentially big liability) with a direct effect on future political, economic, social and cultural fortunes. In some cases, a single highly damaging episode can fundamentally damage a country’s standing, as China found after Tiananmen Square. In such situations, an approach involving a long recovery to rebuild that which is lost is often required.

Some countries may simply wish to promote an opportunity based on a specific single goal, such as wanting to attract more foreign direct investment or increasing tourism — as the ‘Incredible India’ campaign illustrates. Other states, for example Georgia, Rwanda and the Maldives, may want to establish a presence in the public mind because of fears about a specific issue — such as Russian preponderance, building sympathy among donors and investors and tourism in the short term, and/or climate change in the long term, respectively.

Today, of course, it is not just US political consultants who are blazing a trail in this communications and branding industry. London, for instance, has become a major country branding centre fuelled by its favourable European time zone between Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and the Americas.

Looking to the future, demand for elections, communications and branding advice is only likely to grow given the increasing complexity and overcrowded nature of the global information market place. Indeed, in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, some of which remains uncharted territory for the industry, globe-trotting firms may be on the very threshold right now of some of the most challenging work they have yet encountered.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS (the Centre for International Affairs, Diplomacy and Strategy) at the London School of Economics.