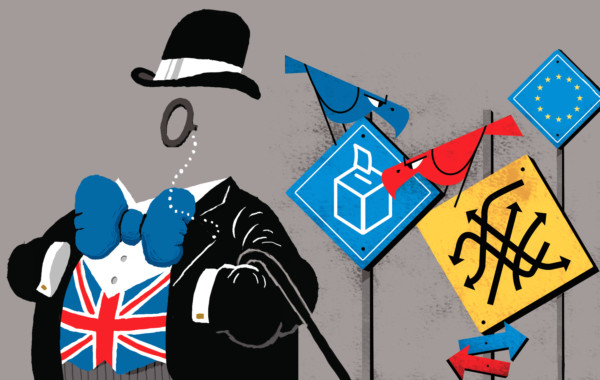

It is easy to be shocked, aghast, at the outcome of Great Britain’s referendum to abandon its European Union membership. Public opinion polling in the lead-up suggested it would be close. When last Thursday’s votes were tallied, there were more backers of British exit, or Brexit for short, than for those preferring to remain. Britain will end more than 40 years of participation in the regional union.

The economic costs looked to be immediately jarring, as the pound’s value fell and the London stock market took a dive in response to the heightened uncertainty. It reached its lowest level since 1985. The top 100 UK companies lost an estimated £120 billion (Dh612 billion) in stock value the day after the vote. Many Brits are rightfully concerned about the lost ease of access for people and goods moving between the Isles and the continent. Britain’s trade, tourism and financial flows, many fear, will be irreparably harmed.

The domestic and international political implications also appear severe. Prime Minister David Cameron, who backed Remain and called for the referendum before the 2015 elections, resigned. The major political parties all backed the status quo as well. There is grumbling that Scottish secession will have a renewal, as most Scots voted to remain. What it means for Northern Ireland and Wales are also open political questions. British lawmakers face the task of managing a process that could take years. Parsing through, deliberating on, and adapting the European regulations will open more political contestation.

Meanwhile, EU leaders worry that other countries will follow, thereby weakening this experiment in Post-Westphalian regional integration. Diminished regulatory coordination among the UK and European allies could have geopolitical consequences for regional rivalries with, for example, Russia, or with sometimes tenuous allies like the United States. There are countless other anticipated by-products and sure to be many more surprises down the road.

Many have been asking why the British would take such an obviously costly, far-reaching and likely regrettable course of action.

Brexit supporters cite a number of reasons for leaving the EU. They essentially boil down to independence and the injuries to national pride that Brussels exacted on the United Kingdom. They claim the EU is over-regulating Great Britain, while putting foreign and corporate interests above those of the British. As a result, Britain is more vulnerable to shocks in the global economy. Britain has less control over the flow of people into its borders, in particular refugees from war-torn Syria who, many fear, could worsen the ethno-religious disharmony and empower those who seek to commit acts of political violence. There is also backlash against under-assimilated eastern Europeans.

Xenophobia and racism

Critics of the move pin it on xenophobia and racism, presuming ‘Leave’ voters oppose the inflow of migrants, refugees, foreign money and other deleterious outsiders who made their way to its shores. Many voters acted out of fear of the invasion of the other.

Such intolerance is typical of economically troubled times, when the tendency is to blame the most vulnerable of society or hidden forces, rather than engage in the more difficult task of understanding the economy or other structural causes for their unhappy state of existence.

Voters’ demographics and news-consuming habits also offer potential clues as to why Brexit passed. Exit backers were older and less educated generally. They tend to make less money, work in non-skilled trades and lack formal qualifications. In other words, they lack the proper training to compete in the global economy while believing they were being squeezed by the consequences of EU membership. They would also be reluctant to rapid social changes that integration in the global economy entails.

Adding up these explanations, it is tempting to understand this measure as reflecting a larger, deep-seated angst about the fragile state of national sovereignty.

Sovereignty is the passionate almost personal concern of nationalists, patriots and ordinary citizens everywhere. The notoriously irresponsible British tabloids agitated for such sentiments over the past four decades. Sovereignty, as the highest political authority, was a key word in the Brexit debate, especially for those calling for Leave votes. This is odd. What does national sovereignty mean for average people who have no command of the state’s instruments and are not of an economic class to determine how the state works? This presumes a rational basis.

The bargain underpinning the EU is that compromises in national sovereignty through accession to regulatory compliance will bring economic and social benefits. Creating a common economic market that could rival the American economy would be a boost to lift all boats. Yet while greater access to markets and labour migration accelerated within the EU, public austerity measures produced cutbacks in social programmes, education and health. For many working people, the benefits of EU membership did not appear to outweigh the stagnation in quality of life they experienced, combined with the loss of security.

The torment of uncertainty around their life chances, and the sense that improvement appeared out of reach, gave rise to popular sentiments that the rapid changes amounted to a loss of control. Everything around them changed, while they stayed the same. Such panic stripped them of faith in the institutions of a state they saw comprised by the all-powerful bureaucrats in Brussels.

One common resort against larger transnational forces and a sense of lost power is nostalgia — a longing for how things used to be in the good old days. Back when the state was strong and sovereign, and stood for its citizens, not the EU elite in Brussels. This is of course a figment of the contemporary imagination. And it displaced the political imagination from the current day to yesteryear. It is essentially fantasy divorced from present day problems.

What is very real, however, are the conditions giving way to such nationalist dreams.

The neoliberal premise of free trade bringing about wealth creation for all did not manifest. Ordinary working people are left to feel they paid the cost of national honour — of which the state is the protector — for questionable, partial, material benefits, which were disproportionately distributed to those who were already well-off. The riches of Brussels went to those who profit the most from trade, banking, finance and so on. Social and economic stratification has such reproductive tendencies, and only further cement resentment.

The rising sense of national pride, one ridden by angst about the state of the changing world, might appear irrational. But it betrays the underlying reason. An observer might miss it if they value the outcome in economic terms and political outcomes alone.

Emotive component

But there is an affective, emotive component. If a frustrated, fearful, working person’s only course of action is collective self-harm — or the status quo — then why not take it? Why shouldn’t they stick it to the globalised, mobile elite, the aristocracy, the corporations, the experts, the mainstream politicians, the media and others who gain from the EU? Such a move would feel good. It would appear to compensate for the damage done to their weakened economic prospects.

Brexit is a sort of martyrdom in the name of a restored state sovereignty. This is of course a matter of perception. How much sovereignty did Great Britain actually sacrifice? Euro-sceptics trotted out a litany of grievances, often to mock the over-specificity of EU regulations. It would be hard to accept that the UK’s fate was actually much worse or unable to navigate the global economy as a result of its belonging.

Those of us mystified by the vote show contempt for the Brexit decision. Some deride it as a demonstration of one of the major shortcomings of democracy, namely when uninformed electorates make crucial decisions. Referendums are among the most democratic means of direct, collective decision-making. There are rightful concerns that public deliberation beforehand was confused, media coverage was agnostic to facts, and mistrust of expertise was absent.

Either way, Brexit produced a confused desire by the majority of Brits for fortifying state sovereignty. It will not fix the underlying problems of economic stratification, withered public safety nets and a national pride injured by its lost investments in imperialism and colonisation.

The state model in general has failed to address the increasingly transnational problems of the world today, including global economic inequality, mass migration, climate change and the whimsical destruction wrought by the transnational finance networks. It is easy to pin these on the institutions like the EU, but many border-defying problems are the direct result of past state actions — the same powers of national sovereignty Brexit supporters seek to bolster.

For example, the flow of Syrian refugees is linked in part to UK’s foreign policy going back to the war in Iraq. Yes, there would have been refugees from the early part of the uprising and war there, but the growth of Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), which led to even more refugees, was an artefact of the Iraq war, which Prime Minister Tony Blair helped commence. This is not to blame the British for Syria, but to show how interconnected parts of the world are and to further point at how inadequate states are at addressing cross-border issues like displaced populations.

British austerity measures since the 1980s were also the product of national policy, even if they had foreign influences. Similarly, British free trade issues and its entanglement in the global economy cannot be blamed on the EU, when the country led the expansion of free trade theory and practice across the globe. So much of the world economic order descended from the expanse of the British Empire, including its financial power and trade routes. And this was a time when the country was at its greatest and most proud in the eyes of its denizens — and repressive to its foreign subjects. There is no going back, and it is an ironic regression that the formerly imperial public fears the so-called invasion of former colonial subjects. The nostalgia for a great Great Britain is fanciful.

The claim to seek national sovereignty is an illusion invested in an image of state authority that simply no longer exists. More important than the economic and political fallout of Brexit is the danger of this new political force that believes in state authority as its saviour and is obsessed with scapegoating the weakest. It is absent any sort of actually corrective politics. Such demands on the state will lead to anti-democratic pressures by commanding the state to solve problems it cannot.

Will Youmans is an assistant professor at George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs.