The ecstatic scenes said it all — Zimbabweans around the world are celebrating the resignation of Robert Mugabe as president. In January 1980, hundreds of thousands of Zimbabweans thronged Zimbabwe Grounds stadium in Highfields township, Harare, to welcome Mugabe back from exile. In March 1980, with reggae icon Bob Marley and Britain’s Prince Charles in attendance, thousands filled Rufaro Stadium to witness the handover from Rhodesia to the new nation of Zimbabwe. Thirty-seven years later, the largest crowds Harare has ever witnessed flooded the streets once again — not to welcome Mugabe in, but to see him out. One simple, taut phrase summed up the day’s events: “This is our second independence day.”

How did it come to this?

These are eight days that have fast-forwarded history, and left Zimbabwe — and the world — shaken. Just two weeks ago, it seemed to be the height of folly to think that Mugabe would leave office on any but his own terms. Emmerson Mnangagwa had been sacked as vice-president, and his followers had been purged; and Grace Mugabe, with ringing endorsements from the women’s and youth leagues, looked set to be elevated to the vice-presidency at the Zanu-PF Congress in less than a month’s time.

Mugabe was expected to stay until the 2018 elections, after which he would hand over the presidency to his wife. It was the prospect of Grace becoming Zimbabwe’s next president that brought in the military. Aware that they had three weeks or less to prevent a dynastic succession and a looming purge of the military itself, Zimbabwe’s military chose, not the audacity of hope, but the hope of audacity, and launched Operation Restore Legacy to stop the rot. What has happened in Zimbabwe is not a people’s revolution in the traditional sense. The Bourbons in France, the Romanov dynasty in Russia, the Shah of Iran, and the autocrats of north Africa’s Arab Spring were all felled by continuous street protests, which ultimately received the support of the military.

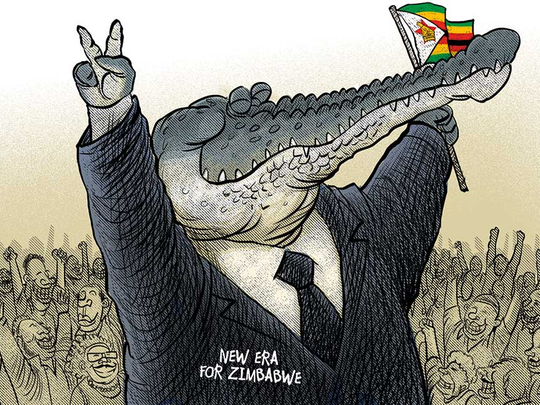

In Zimbabwe, it has been the military who have been the drivers of revolutionary change. What has happened is that an internal party-factional power struggle has inadvertently led to a military-guided popular revolution and the ousting of the Mugabes. Zimbabwe’s military, often seen as the guardians of the state, became instead the guardians of the people. They are seen, for now at least, as liberators, and national heroes. This has been a very Zimbabwean revolution.

So what next?

These are heady days. Zimbabwe is experiencing an almost unprecedented national convergence, with traditional political, economic and social faultlines bridged as Zimbabweans make common cause for change. It is not quite a “Zimbabwe Spring”, but it is perhaps a “Zimbabwe Sunrise”.

The next few days will see the choreography of Mnangagwa’s arrival and Mugabe’s departure. Parliament, which on Tuesday had met to impeach Mugabe, met on Wednesday and Thursday to vote, through constitutional procedures, for a president, who will be given the mandate to form an interim government. Mnangagwa will be further ratified at the Zanu-PF Congress next month, where he will be named and acclaimed as Zanu-PF’s candidate for the next general elections, which constitutionally are due by mid-2018. (Although it is unclear whether this will indeed be the case).

Mnangagwa has a full in-tray. He needs to form a government quickly and has to balance the need for inclusivity and consultation, with the undoubted pressure to reward his followers. With Zimbabwe’s economy nearing paralysis, Zimbabwe’s new president will be under pressure to deliver. Although many are nervous about his history as Mugabe’s ally and his reputation for toughness, Mnangagwa is also an astute political survivor, and has been pro-business and supportive of Zimbabwe’s ongoing re-engagement with the global community.

With Zimbabwe having become a cashless society not by design, but by default; with formal unemployment at 80 per cent and with a largely informalised economy in which much of Zimbabwe’s citizenry has been reduced to penury and classic short-termism, there is plenty for Zimbabwe’s next president to think about. Activists wonder whether he will try to introduce systemic change, or merely go through the motions. He may well face a binary choice between government or governance.

And yet there are also positives: Zimbabwe’s institutions have proven to be resilient, and there is still a reservoir of dedicated and competent professionals in both public and private sectors. Although still laggardly, Zimbabwe had begun to progress in “ease of doing business” indexes. There is a large diaspora who have continued to engage with Zimbabwe; and Zimbabwe’s recent “Look East” and de facto “Look West” re-engagement policies can be built upon. As Mugabe departs, millions of Zimbabweans will tune in to Mnangagawa’s first speech as president.

Many are urging caution and saying that Zimbabwe needs a second, truly democratic revolution. Perhaps. But right now, Mnangagwa should be given a chance. Farai, a friend of mine in Harare, said this: “Yes we know this euphoria may be short-lived. But even if it turns out that we were only happy for a day, let’s make it a brilliant day. Rega tifare nhasi (Let us be happy today).”

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Knox Chitiyo is associate fellow of the Africa programme at Chatham House.