United States President Donald Trump commemorated his first 100 days in office on Saturday. Continuing a frenzied first three months of foreign policy, Trump has multiple meetings with key world leaders, including Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas on Wednesday and Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull on Thursday.

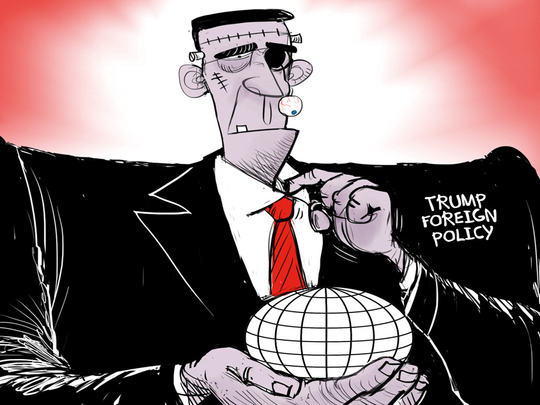

A 100 days into office, and yet, the nature of Trump’s foreign policy remains largely undefined.

Indeed, his period in office so far has been much clearer for his reversing of previous campaign rhetoric and pledges, than fulfilling them.

Trump promised “a new foreign policy direction” in what was seen, in some quarters, as perhaps the biggest potential shake-up since 1945. To be sure, it is already clear that the new administration will challenge some key elements of post-war orthodoxy pursued, in different ways, by Democratic and Republican presidents.

For instance, Trump has already scrapped US involvement in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and pledged to review the North America Free Trade Agreement (Nafta), casting doubt on Washington’s continued commitment to international trade. And he is also rhetorically committed to other key areas of US policy change, including apparent hostility towards the EU project, given his call for more countries to follow the United Kingdom’s lead in voting to leave the bloc.

Yet, while it is clear that the Trump presidency will be different from many of its predecessors in multiple ways, there have also been some remarkable reversals by the president in the last 100 days from his previous pledges. Take the example of Syria, where his ‘America first’ rhetoric indicated that he would not seek to deepen US involvement in that country.

Yet, the president took many by surprise last month by authorising US missile strikes targeted at the Shayrat air base, following an earlier poison gas attack on citizens in a rebel-held town allegedly committed by the Damascus regime. Moreover, US ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, has asserted that the Trump administration was ready to take further military steps in the country if needed.

On the face of it, Trump has also rolled back from his previous rhetoric towards key ‘great powers’, including China and Russia. Trump’s stance towards Russia had the potential to be the most controversial area of his foreign policy, given that he had appeared to (and may still) believe Moscow is not a serious threat to Washington and that there is scope for rapprochement, hinting in January that he could drop economic sanctions if the country “is helpful”. Specifically, he indicated that there are common interests over issues such as preventing Iran secure nuclear weapons, combating terrorism and potentially helping contain China in a new global balance of power.

Yet, partly because of disagreements over Syria, US-Russia relations remain in the deep freeze and Trump has been frustrated in his ambitions of warming ties with Russian President Vladimir Putin, with whom he had previously been widely perceived to have enjoyed a bromance with. Correspondingly, Trump has explicitly said that Nato is “not obsolete” after claiming several times last year that it was.

Trump’s stance towards China has also undergone a significant change and this partially reflects the importance of North Korea in the new US administration’s foreign policy. The US president has acknowledged that China could potentially play a very constructive role in curbing Pyongyang’s continuing provocations, which could become Trump’s first major foreign policy crisis, and he has praised his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping as a “good man”.

This is a turnaround since Trump won office, when he sought to shake-up the bilateral status quo with Beijing, following his telephone call in December to Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen. This was believed to have been the first such communication between the US and Taiwanese presidents since the 1970s and a breach of the so-called ‘One China’ protocol under which, Washington agreed to withdraw diplomatic recognition of the island-nation as part of a deal to open up relations with the mainland.

Earlier this year, it had appeared that Beijing could become the new administration’s bete noire. Underlying this hawkish sentiment appeared to be a conviction that the country represented the primary threat to America’s global interests.

Moreover, the China policy was one key area where Trump appeared relatively aligned with his top team. For instance, both Defence Secretary James Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson had slammed the country’s behaviour, while Steve Bannon, one of the president’s White House aides, wrote about a year ago — before he joined the Trump administration — that “there’s no doubt” that Washington and Beijing will fight a war within a decade.

Going forward, it remains to be seen exactly how US-China relations will pan out during Trump’s presidency, but he has asserted that “everything is now under negotiation” with Beijing and it appears that he may ultimately be looking for a ‘grand bargain’ that would extend beyond the security arena to economics too. Here, one specific measure he wants to see is Beijing floating the yuan: He asserts that the country is “manipulating” its currency by keeping its exchange rate artificially low in order to secure export advantage.

Taken overall, significant uncertainties remain about Trump’s foreign policy some three months into office. While his campaign rhetoric will probably continue to be watered down in multiple areas, a significant recasting could still be on the horizon and his stance towards Russia and China may be key indicators of the degree to which US policy is entering a period of change.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS (the Centre for International Affairs, Diplomacy and Strategy) at the London School of Economics.