By Noah Feldman

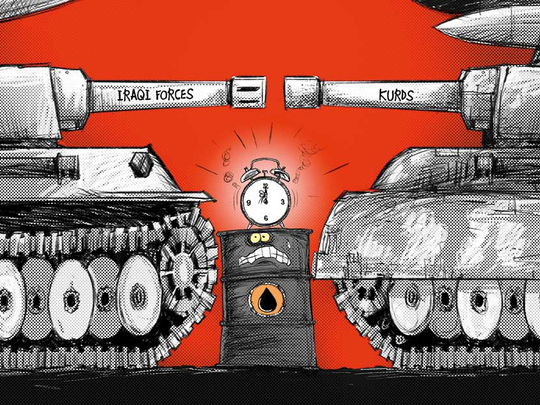

The growing military confrontation between Kurdish and Iraqi forces around Kirkuk has been a long time coming — since 2004, in fact, when Iraq’s Transitional Administrative Law, its interim constitution, flagged the city’s status as disputed territory and deferred resolution into the indefinite future. The conflict combines nationalism, politics and the magic ingredient that makes so many of the region’s problems so hard to fix: oil.

The consequences of an escalating conflict are huge. Kirkuk has the potential to spark a full-on civil war between the central government in Baghdad and the regional government of Kurdistan.

Why Kirkuk? And why now? Immediately after the fall of Saddam Hussain in 2003, the Iraqi Kurds were staking out a claim to the city. Some went so far as to call it the “Jerusalem of Kurdistan.”

The claim to an ancient or even long-term Kurdish identity for the city is highly dubious. Kirkuk was historically diverse, with ethnic Turkmen constituting at least a plurality in the urban core and Kurds a majority in the hinterland well back into the Ottoman period. In 1921, in an unscientific estimate, British occupation forces speculated that the region, as opposed to the city, had 75,000 Kurds and 35,000 Turkmen. As late as 1957, a census focused on the city itself showed a slight plurality of Turkmen (37.6 percent) over Kurds (33.3 per cent).

The impetus for change was the oil, as scholarly research has shown. Over the course of the 20th century, the Baghdad government came to see the Kirkuk fields as its chief source of energy revenue. Consequently, Saddam, as well as some of his predecessors, sought to Arabise the city, moving Kurds and Turkmen out and ethnic Arabs in. From today’s perspective, the process could arguably be considered ethnic cleansing.

As Kurdish nationalism grew over in same era, Kurds began to identify Kirkuk as the rightful possession of a future Kurdish nation-state. There’s nothing like the prospect of monopolising oil revenue to spur nationalist attachments.

After Saddam fell, it was obvious that Kirkuk could become a major flashpoint between Baghdad and the Kurdish region, a prospect that threatened the very possibility of a unified Iraq. The solution adopted in the drafting of the interim constitution was not to seek a solution at all, but to kick the can down the road through an open-ended deferral. (Dislosure: In 2003, I served as senior constitutional adviser to the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq, and advised members of the Iraqi Governing Council on the drafting of the Transitional Administrative Law.)

That may sound irresponsible, but in fact this deferral strategy is common in many constitutions: The hardest problems often can’t be resolved, and so the drafters’ only options are failing to produce a constitution or punting on major issues. For the US Constitution, slavery was the grand deferral. Without the compromise to allow its continued existence, there could have been no Constitution, yet the issue ultimately was the single greatest cause of the US Civil War.

For Iraq’s constitution, Kurdish self-determination in general and the status of Kirkuk in particular were the biggest deferral points. And until now, the compromise has held.

What’s changed is the rise and fall of the Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) in Iraq. Daesh’s rise demonstrated the extreme weakness of the Baghdad government, sending Kurds the message that they may be able to get away with a move towards independence, or at least a greater share of oil revenue. In the course of defeating Daesh, Kurdish forces were able to shift their strategic position by essentially occupying Kirkuk.

The Kurdish forces in the Kirkuk area were a major reason that the regional government was willing to stage its independence referendum last month. From the Kurdish perspective, the timing was never going to be better. The Baghdad government is allied with Iran, which the US administration hates. Turkey is caught up in its own internal troubles after the attempted coup d’tat there. And if the Baghdad government tried to retake Kirkuk, the Americans could plausibly be expected to sit on the sidelines, as has been the case so far.

What’s going to happen next is a delicate question. One possibility is that both sides will pull back from real war-fighting, which could be costly for all without really clarifying the balance of power. Another is that the Baghdad government and the Kurdish regional government will both be willing to fight a limited engagement over Kirkuk, with each side trying to figure out whether the other will be willing to back down.

The scariest possibility is that what begins as a limited fight will grow into something much more like a regional civil war. If that happens, Iran can be expected to support Shiite militias, the same forces that fought Daesh on behalf of Iraq. That might tempt United States President Donald Trump to support the Kurds, an outcome that must tantalise the Kurdish regional government but that would be a reversal of US policy over a decade and a half to try to hold Iraq together as a single country.

Nothing in history is inevitable. But a conflict between Baghdad and the Kurds over Kirkuk comes close. The tragedy is that it’s happening before Iraq has had a chance to consolidate itself into a functioning federal state that could have accommodated both sides.

— Bloomberg

Noah Feldman is a Bloomberg View columnist.