According to press reports, the Trump administration is basing its budget projections on the assumption that the United States economy will grow very rapidly over the next decade — in fact, almost twice as fast as independent institutions like the Congressional Budget Office and the Federal Reserve expect. There is, as far as we can tell, no serious analysis behind this optimism. Instead, the number was plugged in to make the fiscal outlook appear better.

I guess this was only to be expected from a man who keeps insisting that crime, which is actually near record lows, is at a record high, that millions of illegal ballots were responsible for his popular vote loss, and so on: In Trumpworld, numbers are what you want them to be, and anything else is fake news. But the truth is that unwarranted arrogance about economics isn’t Trump-specific. On the contrary, it’s the modern Republican norm. And the question is why.

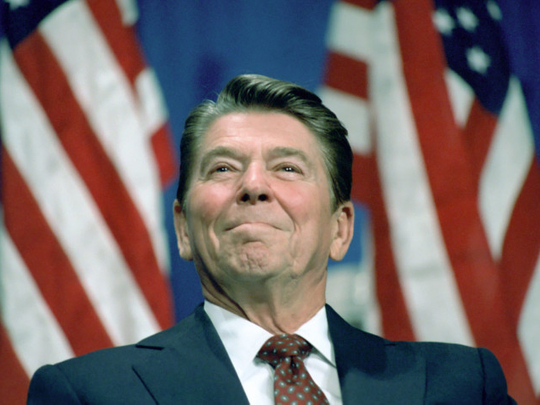

Before I get there, a word about why extreme growth optimism is unwarranted. The Trump team is apparently projecting growth at between 3 and 3.5 per cent for a decade. This wouldn’t be unprecedented: the US economy grew at a 3.4 per cent rate during the Reagan years, 3.7 per cent under Bill Clinton. But a repeat performance is unlikely.

For one thing, in the Reagan years baby boomers were still entering the workforce. Now they’re on their way out, and the rise in the working-age population has slowed to a crawl. This demographic shift alone should, other things being equal, subtract around a percentage point from US growth.

Furthermore, both Reagan and Clinton inherited depressed economies, with unemployment well over 7 per cent. This meant that there was a lot of economic slack, allowing rapid growth as the unemployed went back to work. Today, by contrast, unemployment is under 5 per cent, and other indicators suggest an economy close to full employment. This leaves much less scope for rapid growth.

The only way we could have a growth miracle now would be a huge takeoff in productivity — output per worker-hour. This could, of course, happen: maybe driverless flying cars will arrive en masse. But it’s hardly something one should assume for a baseline projection. And it’s certainly not something one should count on as a result of conservative economic policies. Which brings me to the strange arrogance of the economic right.

As I said, belief that tax cuts and deregulation will reliably produce awesome growth isn’t unique to the Trump-Putin administration. We heard the same thing from Jeb Bush; we hear it from congressional Republicans like Paul Ryan. The question is why. After all, there is nothing — nothing at all — in the historical record to justify this arrogance.

Yes, Reagan presided over pretty fast growth. But Clinton, who raised taxes on the rich, amid confident predictions from the Right that this would cause an economic disaster, presided over even faster growth. Former president Barack Obama presided over much more rapid private-sector job growth than George W. Bush, even if you leave out the 2008 collapse. Furthermore, two Obama policies that the Right totally hated — the 2013 hike in tax rates on the rich, and the 2014 implementation of the Affordable Care Act — produced no slowdown at all in job creation.

Meanwhile, the growing polarisation of American politics has given the country what amounts to economic policy experiments at the state level. Kansas, dominated by conservative true believers, implemented sharp tax cuts with the promise that these cuts would jump-start rapid growth; they didn’t, and caused a budget crisis instead. Last week, Kansas legislators threw in the towel and passed a big tax hike.

At the same time, Kansas was turning hard-right, California’s newly-dominant Democratic majority raised taxes. Conservatives declared it “economic suicide” — but the state is in fact doing fine. The evidence, then, is totally at odds with claims that tax-cutting and deregulation are economic wonder drugs. So why does a whole political party continue to insist that they are the answer to all problems?

It would be nice to pretend that America is still having a serious, honest discussion here, but it isn’t. At this point, America has to get real and talk about whose interests are being served.

Never mind whether slashing taxes on billionaires while giving scammers and polluters the freedom to scam and pollute is good for the economy as a whole; it’s clearly good for billionaires, scammers, and polluters. Campaign finance being what it is, this creates a clear incentive for politicians to keep espousing a failed doctrine, for think tanks to keep inventing new excuses for that doctrine, and more.

And on such matters, Trump is really no worse than the rest of his party. Unfortunately, he’s also no better.

— New York Times News Service

Paul Krugman is a Nobel Prize-winning economist and distinguished professor in the Graduate Centre Economics PhD programme and distinguished scholar at the Luxembourg Income Study Centre at the City University of New York.