On May 13, the Vatican officially recognised the state of Palestine. In reality, the Vatican had already welcomed the United Nations General Assembly vote in 2012 to recognise a Palestinian state. It has treated Palestine as a state since then.

However, what makes May 13 particularly important is that the subtle recognition was put into practice in the form of a treaty which, in itself, is not too important. True, the updated recognition is still symbolic in a sense, but also significant for it further validates the Palestinian leadership’s new strategy, which is aimed at breaking away from the US-sponsored ‘peace process’ into a more internationalised approach to the conflict.

A statement by Vatican spokesperson Rev. Federico Lombardi sums up the Holy See’s decision, which tellingly coincided with the canonisations of two Palestinian nuns from the 19th century — Mariam Bawardi and Marie-Alphonsine Ghattas. “Yes, it’s a recognition that the state exists,” he said, meaning a recognition took place, but with a due acknowledgement that the state had been in existence already.

The Vatican can be seen as a moral authority to many of the 1.2 billion people that consider themselves Roman Catholics. Its recognition of Palestine is consistent with the political attitude of countries that are considered the strongest supporters of Palestinian rights around the world, the majority of whom are located in Latin America and Africa. However, a political message is also unmistakable, as the Vatican now joins Iceland, Sweden — which fully recognised the state of Palestine — and European parliaments, including the British parliament, which overwhelmingly voted in favour of recognising Palestine.

There is more than one way to read this latest development, within the context of the larger Palestinian strategic shift to break away from the disproportionate dependence on American political hegemony over the Palestinian discourse. But it is not all positive and the road for the ‘state of Palestine’, which is yet to exist outside the realm of symbolism, is fraught with dangers. But first, the positive side.

Reasons for optimism:

1. Recognitions allow Palestinians to break away from US hegemony over the political discourse of the ‘Palestinian-Israeli conflict’.

For nearly 25 years, the Palestinian leadership — first the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) and then the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) — came under American influence, starting at the US-led multilateral negotiations between Israel and Arab countries in Madrid in 1991. The signing of the Oslo Agreement in 1993 and the establishment of the PNA the following year gave the US an overriding political influence over the Palestinian political discourse. While the PNA accumulated considerable wealth and a degree of political validation as a result of that exchange, Palestinians as a whole lost a great deal.

2. International recognitions downgrade the ‘peace process’, which has been futile at best, but also destructive as far as Palestinian national aspirations are concerned.

Since the US-sponsored ‘peace process’ was launched in 1993, Palestinians gained little and lost a lot. That loss can be seen mostly in the following: Massive expansion in Israel’s illegal Jewish colonies in the Occupied Territories and the doubling of the number of illegal colonists; the failure of the so-called peace process to deliver any of its declared goals — largely Palestinian political sovereignty and an independent state; and the fragmentation of the Palestinian national cause among competing factions.

The last nail in the ‘peace process’ coffin was put in place when US Secretary of State, John Kerry, failed to meet his deadline of April 2014 that was aimed at achieving a ‘framework agreement’ between the PNA and the right-wing government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The collapse in the process was largely an outcome of a deep-seated ailment where the talks, no matter how ‘positive’ and ‘encouraging’, were never truly designed to give Palestinians what they aspired to: A state of their own. Benjamin Netanyahu and his government (the recent one being arguably the ‘most hawkish’ in Israel’s history) made their intentions repeatedly clear.

Finding alternatives to the futile ‘peace process’, through taking the conflict back to international institutions and individual governments, is surely a much wiser strategy than making the same mistake over and over again.

3. Instead of being coerced into engaging in frivolous talks in exchange for funds, recognition of Palestine allows Palestinians to regain the initiative.

In 2012, Abbas reached out to the UN General Assembly, seeking recognition of Palestine. Once he achieved the new status, he continued to push for his internationalisation-of-the-Palestinian-cause project, although, at times, hesitantly. What is more important than Abbas’s manoeuvres is that with the exception of the US, Israel, Canada and few tiny islands, many countries, including America’s western allies, seemed receptive to the Palestinian initiative — some going as far as confirming that commitment through parliamentary votes in favour of a Palestinian state. The Vatican’s decision to sign a treaty with the ‘state of Palestine’ is but another step in the same direction. But all in all, the movement towards recognising the state of Palestine has grown in momentum to the extent that it is sidestepping the US entirely and discounting its role as the self-declared ‘honest broker’ in a peace process that was born dead.

The US, Israel’s largest military funder, economic supporter and political benefactor, had no right to claim ‘honest’ brokering in peace talks that were positioned to pressure Palestinians and empower Israel. The stage should indeed be open to the international community, as to all nations in the world, to attempt to play a positive role in ending the Israeli occupation and ensuring that international law, which advocates justice for the Palestinian people, is respected.

Thus, it is a good day when America’s disparate political and military influence retreats in favour of a more pluralistic and democratic world. But it is not all good news for the Palestinians because these recognitions come at a cost.

Reasons for doubt:

1. These recognitions are conditioned on the so-called two-state solution idea — itself an impractical starting point for resolving the conflict.

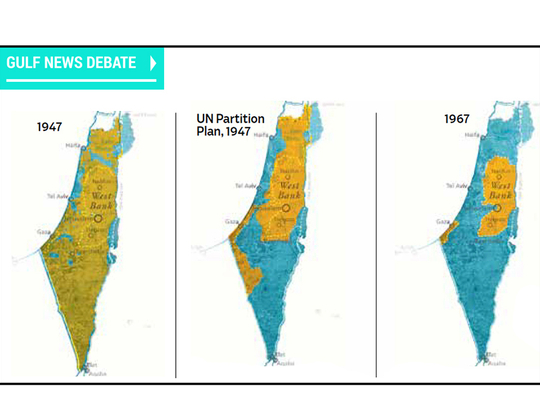

A two-state solution that can introduce the most basic threshold for justice is not possible considering the impossibility of the geography of the Israeli occupation; the huge buildup of illegal colonies dotting the West Bank and occupied Jerusalem; the right of return for Palestinian refugees to their homes; issues pertaining to water rights, etc. That ‘solution’ is a relic of a past historical period when US secretary of state Henry Kissinger launched his shuttle diplomacy in the 1970s; it has no place in today’s world when the lives of Palestinians and Israelis are overlapping in too many ways for a clean break to be realised.

2. Recognitions are validating the very Palestinian president who is serving with an expired mandate — presiding over an unelected government.

In fact, it was Abbas who mostly cooked up the whole Oslo deal, starting secretly in Norway, while by-passing any attempt at Palestinian consensus regarding the inherently skewed process. Since then, he, more or less, stood at the helm, benefiting from the political disaster that he engineered. Should Abbas, now 80, be given yet another chance to shift the Palestinian strategy in a whole different direction? Should these efforts be validated? Or isn’t it time for a rethink involving a younger generation of Palestinian leaders capable of steering the Palestinian national project into a whole new realm of politics?

3. Recognitions are merely symbolic.

Recognising a country that is not fully formed and is under military occupation will hardly change the reality on the ground in any shape or form. The Israeli military occupation, the expanding colonies and suffocating checkpoints remain the daily reality that Palestinians must contend with. Even if Abbas’ strategy succeeds, there is no evidence that, at the end it will eventually carry any actual weight in terms of deterring Israel or lessening the sufferings of Palestinians.

Conclusion

One could argue that the recognition of Palestine is much bigger than Abbas as an individual or his legacy. These recognitions demonstrate that there has been a seismic shift in international consensus regarding Palestine, where many countries in the southern and northern hemispheres seem to ultimately agree that it is time to liberate the fate of Palestine from American hegemony. In the long run, and considering the growing rebalancing of global power, for Palestinians, this is a good start.

However, the question remains: Will there be a capable and savvy Palestinian leadership that knows how to take advantage of this global shift and utilise it to the fullest extent for the benefit of the Palestinian people? A positive answer could help translate international solidarity from the realm of symbolism to a whole new direction.

Ramzy Baroud is an internationally-syndicated columnist, a media consultant, an author of several books and the founder of PalestineChronicle.com. He is currently completing his PhD studies at the University of Exeter. His latest book is My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story (Pluto Press, London).