When Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte announced his country’s “separation” from America in favour of China last week, his choice found resonance in Pakistan, at a significant distance from the Southeast Asian country.

Departing from Manila’s earlier tense relationship with Beijing over a fierce maritime spat that saw the Philippines seek international adjudication over conflicting claims with China in the South China Sea, Duterte arrived in Beijing to seek closer ties with China.

The entire episode has once again served as a powerful reminder of the strength that drives modern-day China — its economic capacity and push for modernisation. Duterte’s public refusal to visit the United States on the grounds that he “will just be insulted there” finds a lot of traction with Islamabad.

After serving US security interests for more than a decade — since the 9/11 terror attacks on America in 2001 that led Pakistan to become Washington’s key ally in the war on terror — Pakistan was let down earlier this summer when the US Congress voted to halt more than $400 million (Dh1.47 billion) in subsidies to support the sale of eight F-16 fighter planes. The pretext made known by US Congress was just that Pakistan had not done enough to clamp down on terrorist groups within its borders.

On the streets of Pakistan, the popular opinion is increasingly tilted against the US and memories of the past are being revived. In 1990, the US, at short notice, had suspended the sale of F-16 fighters to Pakistan on the grounds that the country was advancing its nuclear weapons programme. The decision marked what could best be characterised as an abrupt end to a relationship dating back to the 1980s when Pakistan became a frontline US-backed state to support the resistance to the occupation of Afghanistan by the former Soviet Union.

Later, Pakistan carried out its maiden nuclear tests and since then has actively expanded its nuclear programme. The US found itself practically without any leverage in 1998 to convince a sanctioned Pakistan to step back from carrying out nuclear tests, just three weeks after India carried out a series of nuclear tests.

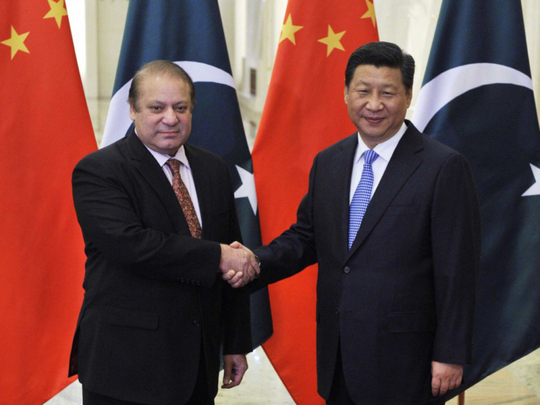

In all these years, irrespective of periods when large US military and economic assistance has been generously given to Pakistan, the element of trust between the two sides has remained far from satisfactory. Meanwhile, Pakistan has continued to further deepen its relationship with China, a country that has remained a time-tested friend for Islamabad.

In the meantime, China’s advancement as a key economic and military power has only strengthened Pakistan’s commitment to stay on course with a country that many Pakistanis like to define as “an all-weather friend”. And when Pakistani leaders use cliches like “deeper than the oceans” and “taller than the Himalayas” to describe their friendship with China, their words reflect sentiment on the streets across Pakistan.

The F-16 episode this year became an instant reminder for Pakistani decision-makers of events that followed in 1990 — US suspension of a promised sale of a batch of F-16s to Islamabad. The earlier suspension only prompted Pakistani leaders to team up with China and launch a project for the development of a new fighter plane to serve the country’s needs. Today, that initiative has been resulted in the successful production of JF-17 ‘Thunder’ — Pakistan’s first ever indigenous fighter plane.

As a follow-up to the effective suspension of US subsidy for the sale of eight F-16s this year, Pakistan has reportedly begun considering options for more advanced Chinese fighter planes. Its only a matter of time before Pakistan will indeed fill the gap left behind by the absence of new F-16s, which have served a useful purpose in the campaign against Taliban militants.

On other fronts, China promises to serve a useful role in bolstering Pakistan’s naval defences with Beijing’s promise of selling eight new submarines to Islamabad. Once inducted in just over a decade from now, the new submarines will play a key role in plugging the gaps in Pakistan’s maritime strategy.

Meanwhile, China’s promise to invest more than $51 billion in Pakistan under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) promises to boost Pakistan’s economic prospects as never before. The corridor plans to link a China-funded deep sea port at Gwadar in northern Pakistan to western China. This will be done through a network of highways, railway lines and oil-and-gas pipelines. Once completed, the CPEC could lift Pakistan’s potential for enhancing its share of global trade and also for encouraging industrialisation within its borders.

Such investment plans are obviously not without China’s own economic interests playing a vital role. To Beijing’s benefit, China-funded new projects like the CPEC will increase demand for Chinese products and help China lift its exports. Moreover, the route through Pakistan is set to significantly shorten the distance and time for travel between China and the Middle East.

Yet, for all the opportunities that come with Pakistan’s close friendship with China, the former can simply not afford to be complacent. It is essential for Pakistan to tackle the many internal challenges surrounding the country, before it can fully reap the benefits from China’s growing footprint in the South Asian country. For Pakistani policy-makers, staying the course with China has come to be seen as a wise choice. Going forward, however, Pakistan needs to ensure that it can work with China to carve out a more promising future for itself. Even though Pakistan may not necessarily follow Duterte’s formal “separation” from the US, its clear that a partnership with China is likely to bring in more dividends than a close alliance with Washington.

Farhan Bokhari is a Pakistan-based commentator who writes on political and economic matters.