At a time when facts jostle with fiction for acceptance, any artistic portrayal of historical or empirical data becomes all the more challenging. More so, it pertains to an ‘in-between’ zone where truth often gets realigned to a mythical template whose fuzzy edges constitute the imaginative and subjective licence that one would accord to an ‘art-for-art’s-sake’ genre. In that sense, Bollywood filmmaker Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s yet-to-be-released magnum opus Padmavati is undoubtedly a challenging project. Tales about 14th-century Rajput queen Padmini or Padmavati’s beauty are as legendary as the various interpretations of the circumstances that presumably led her to self-immolation.

The film Padmavati is a work of art that delves into that ‘in-between’ zone that renders it part-history, part-fiction. And like any other artistic interpretation, it need not necessarily conform to historical or empirical absolutism, so long as it does not take inappropriate liberties with one’s social, cultural and religious sentiments. Bhansali’s Padmavati — according to what the director has said on record — does not deviate so much from the truth and so much into the realm of fancy for it to have warranted the kind of frenzied and violent reactions that have been noticed over the last several months in India.

Legend has it that queen Padmini had committed suicide to prevent her honour from being violated by a marauding Alauddin Khilji, the then sultan of Delhi, who had been enamoured by Padmini’s beauty.

This particular version — the most popular one — that Padmini had committed jauhar (self-immolation) to prevent a lustful Khilji from laying his hands on her, is one of four major interpretations surrounding the legendary queen. There is no conclusive historical evidence to affirm that this popular version of a historical character’s tryst with destiny is a true reflection of what had actually transpired in Chittorgarh Fort in Jaipur in the lead-up to those tumultuous final days of a Rajput queen’s life in medieval India.

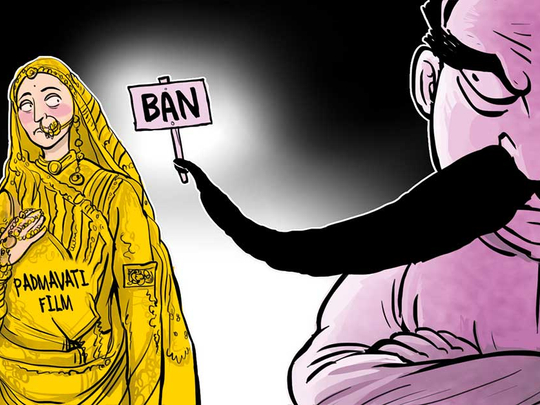

But presumption, rumour, hearsay and a majoritarian dumbing down of artistic sensitivities seem to have taken centre stage in a section of contemporary India. And this has time and again reared its ugly head, demanding the pulping of books, threatening to stop the release of films, desecrating paintings and other works of art … to name just a few of such obnoxious and Goebbelsian excesses, all undertaken in the name of preserving one’s social, religious or cultural sensitivities. A self-proclaimed group that goes by the name of Rajput Karni Sena has now taken up the cudgels against the Bhansali-directed period flick for its apparent – and rumoured – depiction of a dream sequence between Padmavati and Alauddin Khilji. Bhansali himself was physically assaulted by hoodlums during the filming at Jaigarh Fort in Rajasthan, earlier this year. Later, camera and equipment were set on fire during an outdoor shoot in Kolhapur, Maharashtra. Deepika Padukone, who plays Padmavati in the film, has been issued death threats and now the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) has deferred the mandatory pre-screening of the film for certification, citing tawdry technical glitches.

All this despite Bhansali’s repeated assurances that there is no such depiction of a chemistry between Padmavati and Khilji in the film that is a gross misrepresentation of history or an affront to the Rajput community’s honour.

While India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has cited the impending state assembly elections in Gujarat as a reason to stay the release of the film, one of the national spokespersons of opposition Congress has issued a statement, saying that the film should not be released if its contents are in violation of historicity. Meanwhile, at least two state governments – Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, both run by the BJP – have demanded that the film should not be released in those states in view of its objectionable content.

The issue on our hands here is not just a film or its content. The issue is one of freedom of thought and expression and a certain libertarian spirit that any progressive, democratic society would allow its artists, actors, filmmakers, painters, sculptors, orators … The issue is also one of countering lies and half-truths with facts. All those protesting a supposed profanation of Rajput valour in Padmavati, are yet to see the film and establish the veracity of such apprehensions. The least that a progressive society — that encourages a free-thinking, unbiased and independent artistic consciousness to flourish — would do under the circumstances is to allow the work in question to be viewed by the public, before one assumes the role of judge-jury-and executioner. This is the norm in an age and time when ownership of information is not the prerogative of a few, but a domain of the many. And like most free-thinking societies in the world, India too has, for centuries, celebrated its social and intellectual affiliation to a rich and varied tradition of public debate, discussion and scrutiny in order to attain exposition to a higher plane of knowledge and excellence.

This exposition is possible only by encouraging diversity, plurality and multiplicity of thought and expression.

The Rajput Karni Sena’s rambunctious opposition to a film, without even having seen it yet, exposes its intellectual bankruptcy and gullibility to a propagandist cult.

But that is only the symptom, not the disease.

When the CBFC, a state-sponsored institution, withholds certification to a film on flimsy grounds; when state governments, instead of reigning in hoodlums, stay mum to threats of disruption to a film’s screening; when law-enforcing authorities look the other way even after death threats are publicly issued to an actor, then they are indicative of a malignant moral and intellectual sclerosis that runs far deeper and poses a much bigger danger to the polity of a nation than what the fever-pitched rants of a Karni Sena would entail. This is usurpation of intellectual space and cultural identity by way of majoritarian tyranny and nihilism.

Veteran actor Shabana Azmi’s call to boycott next month’s International Film Festival of India (IFFI) over CBFC delaying certification to Padmavati bears an ominous ring, in the sense that CBFC’s act underscores the same nonchalance displayed by the then Congress government at the Centre that went on to host an IFFI even in the aftermath of the murder of poet and playwright Safdar Hashmi on the streets of Shahibabad, near Delhi, in 1989. Shabana calls it “cultural annihilation”.

India must find an answer to such disturbing nomenclature, sooner than later. Or until perhaps the next period flick is released.

Meanwhile, self-styled culture vultures are perked up. Manikarnika: The Queen of Jhansi is on the floors now, slated for a 2018 release. Any takers for a Karni Sena repeat show? Keep watching.