During the past century, Arab-Americans have faced significant obstacles on the way to securing our place in the political mainstream — from pervasive media-projected negative stereotypes to the political pressures used by some groups to deny us a seat at the table.

In addition to these external factors, Arab-Americans have also faced internal obstacles that we had to overcome as we worked to build and empower our community. In many instances, these problems were carry-overs — the impact of competing identities and loyalties that Arab immigrants brought with them as they made their way to the New World. There were village and family rivalries, or disputes between political ideologies or competing interests based on country of origin. There were also issues of sectarian identification.

In order to form a community, all of these had to be surmounted, reconciled, or simply put in their rightful place for Arab-Americans to grow and prosper. To a remarkable extent, we have been successful — more successful than the Arab world has been in healing its multiple divides.

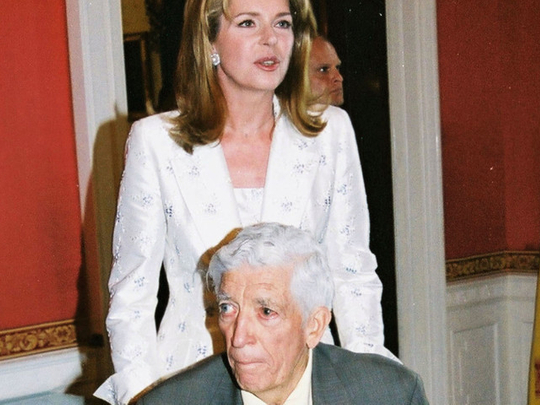

I love telling the story of how a few years back, at our annual Kahlil Gibran ‘Spirit of Humanity Awards’ dinner, we presented a public service award, named after a Syrian American, Najeeb Halaby (the father of Jordan’s Queen Noor), to a Palestinian-American who had served as US Ambassador to the UAE and Syria. The presenter was a Lebanese-American former Congressman who served as Secretary of Transportation. When I later reflected on that night I realised that what we had done could not have happened in the Arab world.

At the height of the Lebanon civil war, an Arab ambassador visited my office. He began with a question: “How do you organise your staff?” I responded by pointing out where the field organising unit had their desks, and in turn where the communications, research, finance, and administrative staffs were seated. He asked again: “No, I mean how do you organise them?” When I repeated “by function”, he came back with “What I mean is: that young man sitting out front, he’s Shiite, isn’t he? How many other Muslims and Christians, etc?”. I said, “If you mean Rami? I have no idea what his religion might be, I never asked him.”

I wasn’t being disrespectful. I honestly didn’t know. In all the years we’ve been working to build a community, we’ve not paid attention to where folks were from or the sect to which they belong. We were building a community that was based on a shared heritage, and we were holding it together by providing services, networking and empowering people.

Over the years, I have seen evidence of this “sense of community” manifesting itself in many different settings. I’ve learnt two lessons in my 40 years of doing this work. As Chair of the Democratic Party’s Ethnic Council, I’ve learnt that every ethnic community shares the same internal pressures. Arab-Americans may hail from 22 countries, making our situation a bit more complex, but even communities that appear to be less complicated have their internal divisions (based on generation, religion, region, ideology, etc) to overcome. Whether Italian, Ukrainian or Armenian — all have had to work to build and sustain a sense of community. I’ve also learnt that the struggle is never-ending. In each new era, new obstacles arise that must be overcome.

To some extent, these internal pressures have been magnified by the rather large numbers of Arab immigrants (over 600,000) who have come to the US since the turn of the century. Many came fleeing war or fear of persecution: Syrians, Iraqis, Somalis, Egyptians and Yemenis. They bring with them the wounds of war and, like every wave that preceded them, they may have their feet planted in America, but their heads and hearts are still “back home”.

Eye on history and the future

While we must be sensitive to these pressures and concerns, we continue to focus on the long-term community building enterprise. We fight the “Muslim ban” and Islamophobia; defend Chaldeans threatened with deportation; work with Copts to protect their right to claim asylum; bring together diverse groups of Syrian-Americans to engage in constructive dialogue; while, at the same time, supporting an amazingly diverse field of Arab-American candidates for public office.

All the while, we keep our eye on history and on the future. What we know is that much of what we are seeing today, we’ve seen before.

As I look at the remarkable group of young Arab-American interns who have come through our doors in recent years, I am reminded of that exchange I had with that ambassador years ago. I don’t know where their parents came from and I don’t know their religion. What I do know is that they have come to us. I also know that we are working with and for them — so that they can find common ground with one another and secure their place in the American mainstream, as Arab-Americans proud of their heritage and their shared identity.

Dr James J. Zogby is the founder and president of the Arab-American Institute, a Washington, DC-based organisation that serves as a political and policy research arm of the Arab-American community.