For all its growth over the past three decades, China is still feeling its way towards assuming a political role commensurate with its position as the world’s second largest economy. It has rested its foreign policy on a mixture of bilateral relationships, mainly based on trade and investment, and a few “core” principles, most notably that sovereign states should not interfere in the internal affairs of one another. As the country’s global role has expanded, however, this recipe needs to be enlarged, and the current terrorist crisis stretching through Europe, Africa and the Middle East presents Beijing with a wake-up call.

If only because of the involvement of its citizens — the execution of a Chinese traveller by Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) and the reported deaths of three of a group of Chinese tourists caught in the hotel siege in Bamako — the People’s Republic cannot stand aside or count on payment of ransoms or other deals to buy safety. One of the prime responsibilities of a state is to protect its citizens and the principle of non-interference abroad makes little sense in the borderless world of terrorism. But joining the fight against Daesh will involve a test that China may find hard to meet.

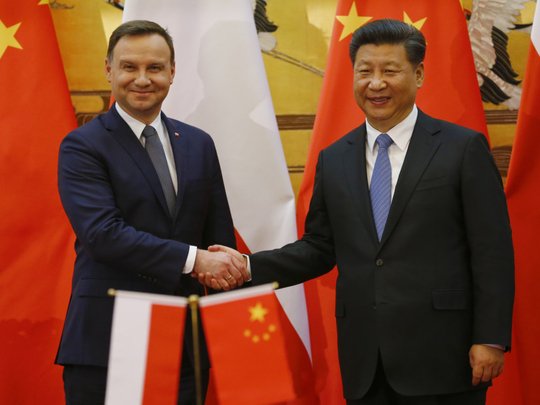

Sending armed forces to participate in the attacks on Daesh in Syria will be such a major wrench away from the traditional line of Beijing’s foreign policy that it would have to be very carefully prepared for. President Xi Jinping has shown an ability to modulate foreign policy this year, for instance, in switching the focus of economic relations to include Europe (Britain in particular with his cash-rich visit in October) and Latin America as well as the long-established stamping grounds of Africa and south-east Asia. He has unveiled an ambitious “one belt, one road” policy of aid and investment in central Asia, stretching to Pakistan and Russia. China has stepped up its involvement in United Nations peace-keeping activities and in anti-piracy operations off the Horn of Africa and elsewhere.

All these involvements have sprung, in one way or another, from China’s economic interests, be it to safeguard trade routes or to create opportunities for mainland firms to operate globally. Joining the battle against Daesh will be different. To begin with, there are serious doubts about China’s ability to project military power. It has the largest standing forces on Earth, with some 2.5 million troops in its army, navy and air force. But foot soldiers are hardly what is needed — it is hard to imagine Chinese boots on the ground in Syria or Iraq. The navy’s development has been mainly in asymmetrical weaponry, such as submarines and missiles designed to knock out American aircraft carriers. Again, hardly the stuff of an anti-terrorist campaign. Though China is developing a stealth military plane, its air power has been held back by the reluctance of its main supplier, Russia, to provide the most advanced weaponry for fear of it being copied while the European Union maintains a 25-year-old arms embargo.

So it is far from evident what China could offer militarily if it joined the anti-Daesh coalition. Equally, it is hard to see the United States or West Europe accepting money, the usual principal ingredient of Chinese collaboration — taking subsidies from Beijing for the fight against terrorism hardly seems politically palatable. But there is a strong reason why the People’s Republic will want to keep involved, in the form of its long-running struggle against Uighur Muslims in its huge western territory of Xinjiang. Beijing insists that the recurrent violence there is the work of fundamentalists and extremist agents crossing from the republics of central Asia.

Heavy security measures have failed to stop the attacks, which have taken scores of lives this year. Last week, Chinese state media reported that security forces had killed 28 alleged members of a group accused of slaying 16 people on an attack on a Xinjiang coal mine. This followed a series of assaults in recent years blamed on Uighur extremists, including the deaths of 33 people at a railway station in south-west China at the hands of knife-wielding assailants in 2014. Beijing says that Uighurs have joined Daesh in the Middle East and that 200 of them arrested in Thailand last year, half of whom were subsequently sent home, were heading for Syria, but no evidence of this has been made public.

Tension is high between the Uighurs and Han Chinese who have migrated to Xinjiang and generally take the best jobs created by investment from the rest of China. Communal riots in the regional capital of Urumqi in 2009 left 200 people dead. Beijing wants to fold the struggle in the region taken by its army 65 years ago into the global campaign, in the process deterring any criticism of its policies in Xinjiang. “Terrorism is the common enemy of human beings,” Xi declared last week. “China will resolutely crack down on any terrorist crime that challenges the bottom line of human civilisation.”

As more and more Chinese citizens travel the world — they make more than 100 million trips abroad each year — the government’s need to be seen to protect them can only grow. But that means joining in the kind of alliances from which Beijing has always held aloof — and accepting that non-intervention may not always apply. While military action is unlikely, Xi may find himself edged towards greater diplomatic involvement as he seeks to live up to his image as the country’s strongest leader for decades. That would be a further step in China evolving a global foreign policy, rather than depending on a network of bilateral trade and investment deals, but it would be new territory that Beijing will approach with the caution it habitually shows in shedding old shibboleths.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd