As I write this, I have a screw loose, and I have to be careful with one corner of the beech-coloured desk on which my laptop, printer and office supplies sit.

If I get too worked up on the computer, the desk moves, and I haven’t been able to tighten the screw that holds the leg in place. Thank you, Ingvar Kamprad, for setting up Ikea, where the desk was bought. And thank you too for designing and selling furniture that is a necessity, but is also a pain when the screws become loose.

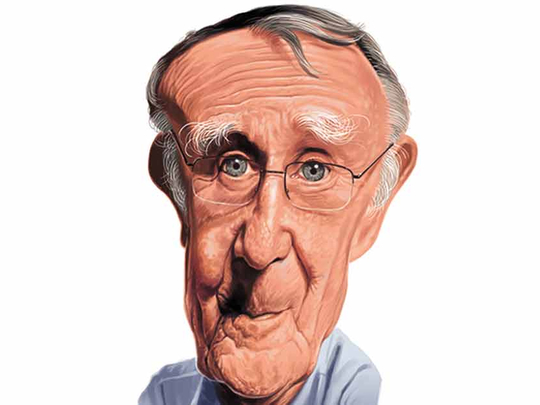

Kamprad passed away last week at the ripe old age of 91.

There’s a familiarity to them, all that brought a sense of home while living on three different continents and four countries over the past three decades.

And, by the way, I did meet him — in truth, it was more of a bumping into — about 20 years ago, at his store in Toronto. I was wandering through Ikea, marvelling at how much stuff can be crammed into so little a space, when I turned a corner at one of the displays and met him. We nodded, and said hello, and it took me a minute or so to twig who he was as he were followed by a lot of serious-looking men and women in bright yellow polo shirts.

That’s OK, he didn’t recognise me either!

Kamprad weren’t a household name, but the company that made you a billionaire most certainly is.

Ikea, the Swedish flat-pack furniture group with 412 stores in 49 countries, bears the name that Kamprad registered in 1943, when, aged 17, he needed to set up a company in order to buy a job-lot of pencils.

It stands for Ingvar Kamprad and Elmtaryd, Agunnaryd, after the farm and village in the southern Swedish region of Smaland where he grew up.

Nearly 75 years on, sales of self-assembly pieces such as a bookshelf called Billy and basics such as the sofa called Klippan, are thought to have amassed him a fortune of $54 billion (Dh198.61 billion).

In 2006, he was placed fourth in Forbes annual list of the world’s wealthiest billionaires. His affairs are complicated, however, involving a family foundation based in Liechtenstein, and he claimed his personal wealth to be far less.

With the exception of perhaps McDonald’s, Ikea has uniquely transcended barriers of class, culture and geography in the late 20th and early 21st century, flying in the face of received retail wisdom by selling the same products with unpronounceable Swedish names all around the world.

The catalogue once had a print run of 150 million copies, and some statistics claimed that more than 10 per cent of the population of Europe had been conceived in an Ikea bed.

Kamprad’s journey to world furniture domination was punctuated by problems. He liked to say, self-deprecatingly, that “no one has had as many fiascos as I have”.

These included boycotts, accusations of Nazism, tax avoidance, plagiarism, and alcoholism.

Yet, those who worked closely with him have suggested he found it painful if things seemed to be going too well — that the struggle and the solution were all part of the same continuum.

You can perhaps take the farmer’s son out of Smaland, but in Kamprad’s case you can’t take Smaland — a harsh, agricultural and punishing region — out of the boy.

Born to Feodor Kamprad, a German immigrant, and Berta on the farm, Elmtaryd, Ingvar kicked off his first business venture — selling matches, bought in bulk in Stockholm, to the villagers — at the age of five. By the time he was 11, he was making enough money from selling seeds to buy himself a racing bike and a typewriter.

In 1943, the first incarnation of Ikea appeared, a mail-order business selling pencils, postcards, and other merchandise. Many farmers in Smaland made furniture as a sideline, and Kamprad soon added these products to his stock.

Sweden was undergoing dramatic and rapid modernisation. During the 1950s, 50,000 farms closed, and between 1946 and 1966, one million flats were built to house those leaving the land.

By 1951, he had made his first million krona.

In 1952, the first flat-pack item, a table called Max, was produced to service those moves. The idea was that if the customer did some of the work, the customer paid less of the price.

In 1971, when Ikea’s flagship store at Kungens Kurva in Stockholm reopened after being gutted by fire, self-service was introduced. The idea remains strong in Ikea’s culture that the customer’s blood, sweat and tears is repaid in savings — something of a Lutheran consumer model.

Eventually he took his production to Poland (and later all over the world), where costs were low, and it was there that his problem with alcohol began. Kamprad dealt with his excessive drinking by drying out for three weeks at a time once a year. In 2014, he claimed his drinking was under control.

When, in 1994, he was faced with charges in the press about his Nazi past, he sent a handwritten fax to all his staff members headed ‘Could not stop the tears’, and recounting his shame.

He denied any direct memories of being a fully paid-up Nazi party member, though it has been said Nazi sympathies were encouraged by his German grandmother, Franziska.

But he could never escape from the reality that he had been very close to Per Engdahl, the Swedish fascist leader, for many years and had even invited him to his second wedding, to Margaretha Stennert, a teacher, in 1963.

Speaking about his first marriage to a secretary, Kerstin Wadling, with whom he adopted a daughter, Annika Kihlbom, and which collapsed in 1960, he said years later: “The whole matter pains me and still hurts. I considered myself a real [expletive].”

Personally, I think we all have that within us. It takes a lot to keep all of the screws tightened all of the time.

— With inputs from agencies